![]()

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AMERICAN SFTV

While SF has a long history in literature, on radio, and in the movies, all predating the advent of television, SFTV has had a significant impact on the shape, popularity, and potential of the genre, in part because of its own implicitly science fictional nature. Indeed television, much like early radio, was initially presented to audiences in a science fictional mode, that is, it was usually framed as a powerful sign of the future and a recurrent icon of the genre. In fact, in the United States the first public television broadcasts originated from the grounds of the 1939 New York World’s Fair, an exposition with the title “Building the World of Tomorrow” that readily evoked thoughts of SF. However, long before television broadcasts were a common part of our cultural experience, the medium had already become a regular feature of SF discourse and a signpost of that “tomorrow.” It was constantly featured in the various popular science magazines early in the century; it was a common fixture in the literature of SF; and in SF films and serials of the 1920s and 1930s, from Metropolis (1927) to The Phantom Empire (1935) to Things to Come (1936) to S.O.S.— Tidal Wave (1939), television was depicted as a ubiquitous, intrusive, and in some cases even dangerous technology (as a title like Murder by Television [1936] dramatically suggests). In light of this ubiquity, Joseph Corn and Brian Horrigan suggest that in the decades leading up to the development of regular television broadcasting, “the idea [my italics] of television in our future heated the popular imagination as few technologies ever have” (24). It signaled progress, technological modernity, and indeed, as the World’s Fair suggested, a world of the future—and given the impact of the Great Depression and World War II, it was a future that very many people eagerly anticipated.

In the context of that sense of cultural anticipation, it seems only appropriate that some of the first efforts at public television broadcasting involved stories precisely about the world of tomorrow. In the United Kingdom, for example, the BBC produced several ambitious adaptations of classic SF literature focused on the future, including versions of Karel Capek’s R.U.R. in both 1938 and 1948, and of H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine in 1948. However, the intrusion of World War II, with its insistence on a devastating now and its prior claim on technical resources needed to expand broadcasting capability and produce television receivers for the public, pushed the development of American SFTV television into the late postwar period when three types of programming would bring the genre into homes on a regular basis: the film serial, the anthology show, and the adventurous space opera. These shows would quickly establish the popularity of SF with the new audience for television, and they would provide models for the genre’s continued development.

The first two of these types are largely important for the way they helped demonstrate the range of potential SF programming. The serial had long been a popular staple of the film industry and a key place-holder for that industry’s SF efforts, as is evidenced by the prewar Flash Gordon (1936, 1938, 1940) and Buck Rogers (1939) films, as well as postwar serials such as Superman (1948), King of the Rocket Men (1949), and Flying Disc Man from Mars (1950). These cliffhangers flashily displayed the adventurous possibilities of SF by mixing rockets, robots, and ray guns with plenty of more conventional fistfights and high-speed car chases. Typically created in 15–20-minute installments, the serial episodes lent themselves to early television programming needs and were among the first products of the American film industry to be sold to both local stations and the fledgling networks for regular broadcast. By 1948 both the ABC and Dumont television networks were devoting blocks of prime-time programming to various sorts of film shorts, including serials, and many local television stations were using public domain serials to produce their own programming (Barbour 234). And since these films were the products of studios like Universal, Columbia, and Republic, they brought to the small screen the sorts of elaborate sets and special effects that film audiences were both accustomed to and practically expected from the genre.

A second type of influential early programming was the SF anthology show, such as Out There (1951–52) and Tales of Tomorrow (1951–53). Because of their format, these shows, as Mark Jancovich and Derek Johnston explain, had to walk a difficult line in early broadcast television, between the more prestigious single-shot dramatic presentation and the supposedly more formulaic series: “As weekly shows rather than single plays, they could build audience loyalty, and by presenting a different story each week they avoided being seen as standardized and low quality” (75). Although neither show ultimately found great success, both offered audiences adaptations of some key literary works in the genre, such as Frankenstein and 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, while also providing opportunities for up-and-coming SF writers like Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke. More important, the very variety of their stories recalled popular radio programs of the 1940s and early 1950s, series like Escape, Inner Sanctum, and Beyond Tomorrow, all of which opened onto a broad spectrum of speculative narrative, while they also suggested the possibility for addressing a more adult audience than was typically attracted by the serials or, by this time, the spate of new space operas.

It is this third type of programming, the space opera, that would have the most significant impact on the early trajectory of SFTV. Introduced in 1949 with Captain Video and His Video Rangers, the live-action space opera adapted many of the conventions of the film serial—in fact, Captain Video, the most popular of these shows, both incorporated serials into its regular broadcast slot and was itself eventually adapted as a big-screen serial—and it would quickly come to dominate early SF broadcasting, so much so that one contemporary commentator noted of these shows, “if you haven’t watched the spacemen on TV, you haven’t lived in the future” (Robinson 63). For slightly more than six years, that future was solidly linked to the exploits of the Captain and a long line of imitators who sought to capture his success with what was predominantly a children’s audience. In addition to Captain Video (1949–55), we might especially note these created-for-television followers: Tom Corbett, Space Cadet (1950–55), Space Patrol (1950–55), Captain Z-Ro (1951–56), Rod Brown of the Rocket Rangers (1953–54), Rocky Jones, Space Ranger (1954), and Captain Midnight (1954–56), along with new television versions of both Buck Rogers (1950–51) and Flash Gordon (1954–55). Operating from Earth but quite easily and frequently venturing into the far reaches of space, these futuristic tales not only offered audiences the familiar thrills of the space opera, with its simplistic characters and conventions, adventuring focus, and well-worn, often overblown plots, but they also gave audiences at least a taste of what Lincoln Geraghty refers to as “the aesthetics of technological innovation and visualizations of the future” (American Science Fiction 27) with their constant invoking of new and intriguing inventions, such as Captain Video’s Opticon Scillometer and Mango-Radar, or Tom Corbett’s Paraloray Gun, along with their cheaply done but visually intriguing sets.

Of course, that visual excitement—an element that, as we have noted, viewers already associated with cinematic SF—was somewhat qualified by these series’ minimalist special effects. As John Ellis reminds us, the early television experience was characterized by a “radically different” weighting of the image than we are used to in the cinema, as we are also accustomed to today with our digital, high-definition, even 3-D home theater systems(Visible 127). With its small screen, often live-action presentation, and limited camera work, these television adventures were for the most part distinctly “pared down” (112) visual events. But those experiences offered audiences another sort of pay-off. For with their repeated depictions of video screens and video monitoring devices, with their stylistic reliance on reaction shots and looks of outward regard, and with their embedding of commercials that frequently used the series’ stars in character as product spokesmen, these shows also demonstrated a level of self-consciousness about television story-telling. It is as if they were all engaged—and trying to engage us—in another sort of SF adventuring and exploring: exploring how SF narrative might best function in this new medium and how audiences, especially the children’s audience at which much of this early work was aimed, might best relate to the medium.

Some of this same impulse would be further developed in the next major wave of SF programming, a return to the earlier anthology format that would, according to M. Keith Booker, mark “the maturation of science fiction television as a genre" (Science 6). Shows like the Ivan Tors and Maurice Ziv-produced Science Fiction Theatre (1955–57), which began each episode with the assurance that it would “show you something interesting”; Rod Serling’s justly famous and expensively produced The Twilight Zone (1959–64), which promised to “unlock … another dimension of space and time”; and the more special effects-oriented The Outer Limits (1963–65), which told viewers to “sit quietly and we will control all that you see and hear”—these all directly addressed an implicitly adult audience, promising them something new, something that would capitalize on the new medium’s (as well as the genre’s) immense possibilities. And with their generally first-rate scripts, written by such figures as Jack Finney, Ivan Tors (Science Fiction Theatre), Richard Matheson, Charles Beaumont, Rod Serling (The Twilight Zone), Joseph Stefano, and Harlan Ellison (The Outer Limits), they consistently provided SF drama that competed well with the more conventional theater-like dramatic productions that were so popular on American television in the 1950s and 1960s, shows like General Electric Theater, Kraft Television Theater, and Playhouse 90.

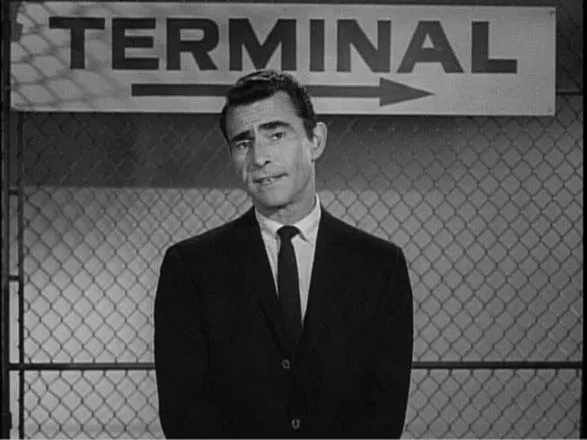

Arguably the most important of all SFTV shows, and one that would subsequently be revived twice (1985–89 and 2002–03), The Twilight Zone appeared at a time when the Western had replaced the SF space opera as the most popular programming for younger audiences. In fact, when it premiered in 1959, nine of the top twenty national series were Westerns. But The Twilight Zone’s success with an older audience helped counter a growing sense that the genre, as it had been embodied in the early space operas, was both moribund and essentially “a subliterary form of culture designed to appeal to children or to … lowbrow plebeian tastes” (Booker, Science 8). Its critical and popular success was due not only to its higher budgets, talented writers, and obvious parallels to the highbrow live-action dramatic anthology shows—for which Rod Serling himself had previously labored—but also to its rather different style (Figure 1.1).

The Twilight Zone was shot on film, and used the various set, prop, and costume resources available at the MGM movie studio where most of the episodes were created. Furthermore, it was photographed by veteran cinematographers like George T. Clemens and directed by established Hollywood directors, including Richard Donner, Don Siegel, and Jacques Tourneur. Moreover, The Twilight Zone often foregrounded that same emphasis on video and technologies of reproduction that was commonly featured in the space operas. As a result, Jeffrey Sconce’s description of the show as a kind of “perverse ‘unconscious’ of television” (134) might well be extended to suggest that it represented a cultural unconscious as well, as it pointed to the already media-haunted nature of contemporary America, an America that, in light of the ongoing space race and the international tensions of the Cold War, was very much primed to look at the future more seriously and with a bit more anxiety than had audiences for the earlier space operas.

Figure 1.1 Creator Rod Serling introduces his groundbreaking The Twilight Zone

Not only was The Twilight Zone a more serious SF effort, but it also fully exploited its anthology format, opening the door to a variety of narrative possibilities. For the series, much like the best of the period’s SF magazines, ranged across the spectrum of narrative types that had become identified with the genre: stories of space adventuring, of utopian and dystopian societies, of alien encounters and invasion, of time and dimensional travel, of extraordinary inventions, of alternate worlds or dimensions, as well as comic takes on many of these story types. As a result, The Twilight Zone also helped spur a revisioning of the space opera, an effect that would show most notably in two of the most important and influential of subsequent SF series, both of which debuted in the 1960s: the British Doctor Who (1963–89, 1996, 2005–present, and first appearing in American syndication in 1978) and Star Trek (1967–69). Both series have obvious roots in the earlier flood of space operas, with Doctor Who, the longest running of all SF series, clearly recalling a show like Captain Z-Ro (1951–56) with its educational tales of travels to real historical events in each episode, and Star Trek, which has generated more spin-offs than any other series, exploiting the potential of those previous adventure shows by emphasizing the infinite wonders of “space, the final frontier,” as its epigraph weekly announced.

Both of these series also underscored the larger promise that was starting to be realized for the television medium, what we might refer to as their televisuality. For Doctor Who, with the Doctor’s TARDIS as his iconic travel vehicle, literally opened up a new dimension for audiences. The Doctor’s surprised companions when first introduced to the vehicle repeatedly observed, “it is larger inside than out,” and they would then exit the TARDIS to encounter a new time and place, indeed a different reality; and in the process they would echo the similarly amazing experience that the series’ audience was supposed to enjoy with each episode. Star Trek’s own iconic vehicle, the starship Enterprise, with its panoramic viewing screen—which pointedly had a wider aspect ratio than any television screen of the period—always seemed to be positioning viewers not only to go “where no man has gone before,” as its introductory narration promised, but also to see what (and as) no one had seen before, at least on network television (Figure 1.2). While these shows were justly prais...