eBook - ePub

Splintering Urbanism

Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition

- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Splintering Urbanism

Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition

About this book

Splintering Urbanism makes an international and interdisciplinary analysis of the complex interactions between infrastructure networks and urban spaces. It delivers a new and powerful way of understanding contemporary urban change, bringing together discussions about:

*globalization and the city

*technology and society

*urban space and urban networks

*infrastructure and the built environment

*developed, developing and post-communist worlds.

With a range of case studies, illustrations and boxed examples, from New York to Jakarta, Johannesberg to Manila and Sao Paolo to Melbourne, Splintering Urbanism demonstrates the latest social, urban and technological theories, which give us an understanding of our contemporary metropolis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Splintering Urbanism by Steve Graham,Simon Marvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 INTRODUCTION

Networked infrastructures, technological

mobilities and the urban condition

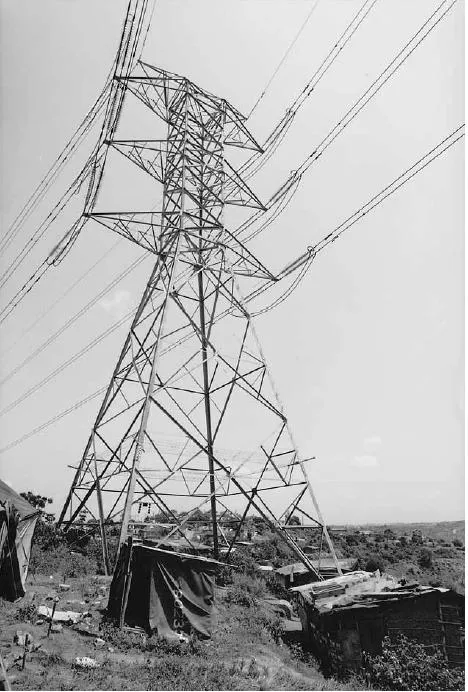

Plate 3 Electric power lines near Durban, South Africa, which run through Umlazi township without serving any of the people who live there. Photograph: Photo Oikoumene, World Council of Churches

A critical focus on networked infrastructure – transport, telecommunications, energy, water and streets – offers up a powerful and dynamic way of seeing contemporary cities and urban regions (see Dupuy, 1991). When our analytical focus centres on how the wires, ducts, tunnels, conduits, streets, highways and technical networks that interlace and infuse cities are constructed and used, modern urbanism emerges as an extraordinarily complex and dynamic sociotechnical process. Contemporary urban life is revealed as a ceaseless and mobile interplay between many different scales, from the body to the globe. Such mobile interactions across distances and between scales, mediated by telecommunications, transport, energy and water networks, are the driving connective forces of much-debated processes of ‘globalisation’.

In this perspective, cities and urban regions become, in a sense, staging posts in the perpetual flux of infrastructurally mediated flow, movement and exchange. They emerge as processes in the distant sourcing, movement and disposal of water reserves and the remote dumping of sewage and waste. They are the hotbeds of demand and exchange within international flows of power and energy resources. They are the dominant sites of global circulation and production within a burgeoning universe of electronic signals and digital signs. They remain the primary centres of transnational exchange and the distribution of products and commodities. And they are overwhelmingly important in articulating the corporeal movements of people and their bodies (workers, migrants, refugees, tourists) via complex and multiple systems of physical transportation.

The constant flux of this urban process is constituted through many superimposed, contested and interconnecting infrastructural ‘landscapes’. These provide the mediators between nature, culture and the production of the ‘city’. There is the ‘electropolis’ of energy and power. There is the ‘hydropolis’ of water and waste. There is the ‘informational’ or ‘cybercity’ of electronic communication. There is the ‘autocity’ of motorised roadscapes and associated technologies. And so on. Importantly, however, these infrastructural ‘scapes’ are not separated and autonomous; they rely on each other and co-evolve closely in their interrelationships with urban development and with urban space.

How, then, can we imagine the massive technical systems that interlace, infuse and underpin cities and urban life? In the Western world especially, a powerful ideology, built up particularly since World War II, dominates the way we consider such urban infrastructure networks. Here, street, power, water, waste or communications networks are usually imagined to deliver broadly similar, essential, services to (virtually) everyone at similar cost across cities and regions, most often on a monopolistic basis. Fundamentally, infrastructure networks are thus widely assumed to be integrators of urban spaces. They are believed to bind cities, regions and nations into functioning geographical or political wholes. Traditionally, they have been seen to be systems that require public regulation so that they somehow add cohesion to territory, often in the name of some ‘public interest’.

Infrastructure operators are assumed in this ideology to cover the territories of cities, regions and nations contiguously, like so many jigsaw pieces. They help to define the identity and development of their locality, region or nation in the process. The assumption, as Steven Pinch argued in his classic book Cities and Services, is that utility supplies (and sometimes public transport and telecommunications networks, too) are ‘public local goods which are, generally speaking, freely available to all individuals at equal cost within particular local government or administrative areas’ (1985, 10). The implication is that, compared with other ‘point-specific’ urban services like shops, banks, education and housing, they are of relatively little interest to urban researchers because, to all intents and purposes, they don’t really have an urban geography in the conventional sense.

What, then, are we to make of the range of examples in the Prologue, which seem so contradictory to such assumptions? What is happening to the previously sleepy and often taken-for-granted world of networked urban infrastructure? How can we explain the emergence of myriads of specialised, privatised and customised networks and spaces evident in the above examples, even in nations where the ideal of integrated, singular infrastructures – streets, transport networks, water grids, power networks, telephone infrastructures – was so recently central to policy thinking and ideology? And what might these emerging forms of infrastructure development mean for cities and urban life across an urbanising planet?

To us, these stories, and the many other tales of networked infrastructure in this book, raise a series of important questions. Are there common threads linking such a wide range of cases? Are broadly common processes of change under way across so many places and such a wide range of different infrastructure networks? How can we understand the emerging infrastructure networks and urban landscapes of internationalising capitalism, especially when the study of urban infrastructure has been so neglected and so dominated by technical, technocratic or historical perspectives? How is the emergence of privatised, customised infrastructure networks across transport, telecommunications, energy and water – like the ones discussed above – interwoven with the changing material and socioeconomic and ecological development of cities and urban regions? And, finally, what do these trends mean for urban policy, governance and planning and for discussions about what a truly democratic city may actually mean?

The rest of this book will address these questions through an international and transdisciplinary analysis of the changing relationship between infrastructure networks, the technological mobilities they support, and cities and urban societies. In this first chapter we set the scene for this discussion. We do so in six parts. First, we introduce the complex interdependences of urban societies and infrastructure networks. Second, we explore how contemporary urban change seems to involve trends towards uneven global connection combined with an apparently paradoxical trend towards the reinforcement of local boundaries. In the third and fourth parts we move on to analyse why Urban Studies and related disciplines have largely failed to treat infrastructure networks as a systematic field of study. We point out that, instead, it has widely been assumed that technologies and infrastructures simply and deterministically shape both the forms and the worlds of the city, and wider constructions of society and history. Fifth, we explore those moments and periods which starkly reveal the ways in which contemporary urban life is fundamentally mediated by such networks: collapses and failures. We close the chapter by drawing up some departure points for the task of the remainder of the book: imagining what we call a critical urbanism of the contemporary networked metropolis.

TRANSPORT, TELECOMMUNICATIONS, ENERGY

AND WATER : THE MEDIATING NETWORKS

OF CONTEMPORARY URBANISM

Our starting point in this book is the assertion that infrastructure networks are the key physical and technological assets of modern cities. As a ‘bundle’ of materially networked, mediating infrastructures, transport, street, communications, energy and water systems constitute the largest and most sophisticated technological artefacts ever devised by humans. In fact, the fundamentally networked character of modern urbanism, as Gabriel Dupuy (1991) reminds us, is perhaps its single dominant characteristic. Much of the history of modern urbanism can be understood, at least in part, as a series of attempts to ‘roll out’ extending and multiplying road, rail, airline, water, energy and telecommunications grids, both within and between cities and metropolitan regions. These vast lattices of technological and material connections have been necessary to sustain the ever-expanding demands of contemporary societies for increasing levels of exchange, movement and transaction across distance. Such a perspective leads us to highlight four critical connections between infrastructure networks and contemporary urbanism that together form the starting points of this book.

CITIES AS SOCIOTECHNICAL PROCESS

First, economic, social, geographical, environmental and cultural change in cities is closely bound up with changing practices and potentials for mediating exchange over distance through the construction and use of networked infrastructures. ‘Technological networks (water, gas, electricity, information, etc.) are constitutive parts of the urban. They are mediators through which the perpetual process of transformation of Nature into City takes place’ (Kaika and Swyngedouw, 2000, 1). As Hall and Preston put it, in modern society ‘much innovation proves to depend for its exploitation on the creation of an infrastructural network (railways; telegraph and telephone; electricity grids; highways; airports and air traffic control; telecommunications systems)’ (1988, 273).

In a sense, then, the life and flux of cities and urban life can be considered to be what we might call a series of closely related ‘sociotechnical processes’. These are the very essence of modernity: people and institutions enrol enormously complex technological systems (of which they often know very little) to extend unevenly their actions in time and space (Giddens, 1990). Water and energy are drawn from distant sources over complex systems. Waste is processed and invisibly shifted elsewhere. Communications media are enrolled into the production of meaning and the flitting world of electronic signs. And people move their bodies through and between the physical and social worlds of cities and systems of cities, either voluntarily or for pleasure or, it must be remembered, through the trauma and displacement of war, famine, disaster or repression.

‘ONE PERSON’S INFRASTRUCTURE IS ANOTHER’S

DIFFICULTY ’ : URBAN INFRASTRUCTURE NETWORKS

AS ‘CONGEALED SOCIAL INTERESTS’

Second, and following on from this, infrastructure networks, with their complex network architectures, work to bring heterogeneous places, people, buildings and urban elements into dynamic relationships and exchanges which would not otherwise be possible. Infrastructure networks provide the distribution grids and topological connections that link systems and practices of production with systems and practices of consumption. They unevenly bind spaces together across cities, regions, nations and international boundaries whilst helping also to define the material and social dynamics, and divisions, within and between urban spaces. Infrastructure networks interconnect (parts of) cities across global time zones and also mediate the multiple connections and disconnections within and between contemporary cities (Amin and Graham, 1998b). They dramatically, but highly unevenly, ‘warp’ and refashion the spaces and times of all aspects of interaction – social, economic, cultural, physical, ecological.

Infrastructure networks are thus involved in sustaining what we might call ‘sociotechnical geometries of power’ in very real – but often very complex – ways (see Massey, 1993). They tend to embody ‘congealed social interests’ (Bijker, 1993). Through them people, organisations, institutions and firms are able to extend their influence in time and space beyond the ‘here’ and ‘now’; they can, in effect, ‘always be in a wide range of places’ (Curry, 1998, 103). This applies whether users are ‘visiting’ web sites across the planet, telephoning a far-off friend or call centre, using distantly sourced energy or water resources, shifting their waste through pipes to far-off places, or physically moving their bodies across space on highways, streets or transport systems.

The construction of spaces of mobility and flow for some, however, always involves the construction of barriers for others. Experiences of infrastructure are therefore highly contingent. ‘For the person in the wheelchair, the stairs and door jamb in front of a building are not seamless subtenders of use, but barriers. One person’s infrastructure is another’s difficulty’ (Star, 1999, 380). Social biases have always been designed into urban infrastructure systems, whether intentionally or unintentionally. In ancient Rome, for example, the city’s sophisticated water network was organised to deliver first to public fountains, then to public baths, and finally to individual dwellings, in the event of insufficient flow (Offner, 1999, 219).

We must therefore recognise how the configurations of infrastructure networks are inevitably imbued with biased struggles for social, economic, ecological and political power to benefit from connecting with (more or less) distant times and places. At the same time, though, we need to be extremely wary of the dangers of assigning so...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PLATES

- FIGURES

- TABLES

- BOXES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PROLOGUE: TALES OF THE NETWORKED METROPOLIS

- 1. INTRODUCTION: NETWORKED INFRASTRUCTURES, TECHNOLOGICAL MOBILITIES AND THE URBAN CONDITION

- PART ONE: UNDERSTANDING SPLINTERING URBANISM

- PART TWO: EXPLORING THE SPLINTERING METROPOLIS

- PART THREE: PLACING SPLINTERING URBANISM

- POSTSCRIPT: A MANIFESTO FOR A PROGRESSIVE NETWORKED URBANISM

- GLOSSARY

- BIBLIOGRAPHY