- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Coastal Defences aims to present the broad spectrum of methods that engineers use to protect the coastline and investigates the sorts of issues that can arise as a result. The first section of the book examines 'traditional' hard techniques, such as sea walls and groynes, whilst the second looks at the more recent trend of using techniques more sympathetic to nature. By looking at each of the main methods of coastal protection in detail, the book investigates the rationale for using each method and the consequent management issues, presenting a case for and against each of the techniques.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Introduction

1 Introduction to coastal defences

Introduction

In its basic sense, the coastline represents the boundary between marine and terrestrial environments — the place where the land meets the sea. This simplistic statement may describe the coast as a geographic feature, but it does not highlight its complexity; the coast is not a permanent line to be drawn on a map, but a dynamic environment in which land and sea are constantly interacting (eroding and accreting) in response to external factors, both natural and anthropogenic in origin, and acting on a whole range of time scales (Table 1.1). Historically, humans have responded to erosion by building structures to resist it, so ensuring that the boundary between land and sea remains fixed and permanent. This is done under the assumption that the coastline is a feature which has always been in its current position and in its current form, and must never be allowed to change. In more recent times the wisdom of this approach has been questioned and radical changes in how the coastline is protected and managed have occurred.

These changes have been largely driven by new research developments which have provided a greater understanding of how coasts work. A notable example is the work of Per Bruun in the 1960s on the effects of rising sea levels on coastal landforms. More recently, such research efforts have become more focused and coordinated, leading to national and international collaborative programmes. One example is a UK-based programme established to investigate coastal processes and their interaction with engineering structures on a scale reaching beyond the local, scheme-based approach. This project, entitled the Coastal Area Modelling for Engineering in the LOng Term (CAMELOT), was set up to establish and validate coastal models in order to facilitate better and more informed management of long-term coastal change (MAFF 1993). A field-based validation study was also undertaken as part of the wider Land-Ocean Interaction Study (LOIS), funded by a leading UK research council. To date, this work has produced a series of coastal models, such as COSMOS-2D and COSMOS-3D, for the study of beach profile and nearshore bed changes, PISCES for the modelling of coastal behaviour, and BEACHPLAN, which can model variations in coastal position over time. A similar project is the European Union (EU) funded MArine Science and Technology (MAST) initiative, which has involved close links with US facilities, such as the coastal monitoring facilities at Duck in North Carolina.

Table 1.1 Time scale of coastal changes in relation to both absolute and human time scales (After French, 1997).

By using output from these and other research programmes, we now have a more complete understanding of how coastal processes operate, and how processes operating on one part of the coast may be closely linked to the behaviour of adjacent beaches in respect of sediment supply and sediment movement. A more holistic approach can therefore be adopted towards coastal protection which takes into account the knock-on implications of defending one part of the coast for those adjacent to it. For example, building a sea wall in front of an eroding cliff may well stop that area from eroding, but it will also stop the sediment from the eroding cliff entering the coastal sediment budget. If this sediment were important in supplying beaches down drift with sand, this supply would cease and these beaches would lose their sediment supply and may start to erode. Hence, solving one erosion problem has created another. Figure 1.2 illustrates this process for a hypothetical situation, which will be returned to shortly.

The concept of protecting the coast means different things to different people. These contrasting opinions arise from the plethora of concerns relating to the coast, including industry, tourism and residential sectors. It is obvious to people who live at the coast that their homes and businesses should be protected from flooding and loss of land and, because of this, it is paramount that sea walls, or some other engineered structure, hold the sea in place and do not allow it to encroach onto the land. In contrast, it is equally obvious to many coastal managers that the best way to look after the coastal environment is to leave it in as natural a state as possible, and to allow sediment to build up and protect the coast by natural processes. Immediately, therefore, there is a major difference of opinion between the people who live at the coast, and those who are charged with managing it. The question of which opinion ‘wins’ will depend on a multitude of factors, ultimately reducing to how much the threatened land is worth. A second issue here concerns the nature of the coast itself. The question of ‘naturalness’ with respect to the coast will occur time and time again throughout subsequent chapters. Whenever coasts are defended, or when people interact with them in some way, there is a degree of artificiality imparted in them. This may lead to changes in coastal processes, and thus in the behaviour of coastal landforms. The question, therefore, is, just what is a ‘natural’ coastline or, more philosophically, are there any ‘natural’ coastlines left, given the amount of interference on the world’s coastline?

The coastline is generally a highly populated area, both in respect of high resident numbers, and a large transient population who visit during the summer as tourists. Estimates from Goldberg (1994) state that 50 per cent of the world’s population lives within 1 km of the coastal zone, a figure expected to increase by 1.5 per cent by 2010. Given this large population, it is not surprising that many coastal areas are highly developed and, thus, have an associated high land value. In such situations, it is imperative that the development is protected from the sea; some form of defence structure is an obvious solution to the protection of these areas. In contrast, however, smaller areas of development, such as individual hamlets and villages, or individual farmsteads, do not command such high land values and do not justify such expensive defences. As a result, there is an increasing tendency to reject defence construction. This problem touches on another important debate in coastal management, that of whether to construct defences or not. For reasons which will become apparent in subsequent chapters, sparsely developed coasts are increasingly being left undefended in order to maintain sediment supply to the coastal zone, even if this leads to the loss of property.

Historical background to coastal defences

Given that the boundary between land and sea is highly dynamic and constantly changing, one could be forgiven for questioning why some major coastal developments found on today’s coasts were ever built. Clearly, however, this is an historical issue and we cannot equate the original reasoning with the relatively well informed decision making of today’s planning process.

Initially, sea defences were not built to protect development but were constructed to protect land claim (land taken from the marine environment and converted to agricultural land) from inundation by the sea. Evidence of this process includes Romano-British land claim in many areas such as the Severn Estuary (Allen and Fulford 1990), tenth-century reclamations in the Severn (Allen 1986), twelfth-century reclamations on the Dutch coast (de Mulder et al. 1994), thirteenth-century reclamations in Morecambe Bay (Gray and Adam 1973), seventeenth-century reclamations along the north Norfolk coast (Cozens-Hardy 1924), and seventeenth-century reclamations bordering the Dutch Wadden Sea (de Jonge et al. 1993). Increasingly, however, as international trade increased and industrialisation occurred, land also started to be claimed for development as a supply of cheap, flat land close to ports and water supplies for industrial use. This development was driven by nations’ need to establish a solid industrial and economic base. Much of this industrial expansion necessitated the development of ports and harbours, thus impinging on sheltered areas of coasts, such as lagoons, estuaries and embayments. Similarly, industry requiring water in large quantities found the coast an ideal setting. These developments often involved altering the natural coast by land claim and dredging. Although unaware of this at the time, these developers were initiating many of our current coastal problems as the natural coastal environment became more artificially constrained by man-made structures (see French 1997, Chapter 4, for discussion). Nobody would argue that ports and harbours are unimportant. They play a vital role in a nation’s economic and industrial base. Since they are essential facilities, coastal managers need to incorporate them into the overall coastal strategy in as accommodating a way as possible.

Although land claim and port development initiated artificial coastal modification, since the onset of the nineteenth century it also started to become fashionable to ‘take the sea air’ (Goodhead and Johnson 1996). This trend started a new pressure on the coast, that of amenity and leisure use. During the nineteenth century, resort areas began to develop in Europe and, by the early twentieth century, in the USA as well. By the late twentieth century, increased leisure time and prosperity meant that the tourist market grew; many areas caught the tourism ‘bug’, and allowed development of coastal areas for tourism. This, again, put new pressures on the coast, requiring further modification of the natural environment (see French 1997, Chapter 5, for discussion).

This drive for economic prosperity has produced many defence problems for coastal areas, ironically costing large amounts of money to put right. Howard et al. (1985) illustrates these issues for the American shoreline, and shows how millions of dollars have been spent in response to increased coastal problems due to development. Furthermore, some of this defence work has produced a new set of problems for adjacent coastlines by causing increased erosion which has, in some cases, caused the loss of the very property which schemes originally set out to protect.

However, criticism of historical developers cannot always be justified. All the time that a stretch of coast is accreting and developing seawards, the development of the shoreline or the claiming of part of the intertidal zone for development does not pose too great a problem. In such situations, it is understandable that areas of newly formed land were considered available for development. In reality, however, by claiming this land and constructing a line of coastal defence, we are, in fact, artificially moving the coastline seawards, and by building infrastructure on that land, we are committing ourselves to protecting it from any future changes in coastline position. As the accretion/erosion cycle completes and beaches disappear through erosion, these same coastal developments suffer and demand for protection increases.

Problems of a static coastline

Perhaps the main problem with hard defences is that, once built, they fix the coastline in the position it was in at the time of construction. However, coastlines are not static structures; they migrate landwards and seawards over a variety of time scales in response to forcing factors, such as sea level (SL), wave climate, and seasons. The type of coastline will govern the severity of the restrictions; for example, dune coasts will fluctuate seasonally to changes in sediment transfer to and from the beach without which the complex dynamic stability of the dune/beach system will be lost. On cliffed coasts, the main problem lies with the input of sediment to the coastal sediment budget, the loss of which can have important repercussions for the beaches down drift.

The problems of a static coastline can be summed up as follows:

- inability to respond to sea level changes in the medium and long term (coastal squeeze);

- cessation of beach/dune interactions;

- cessation of sediment inputs to the sediment budget;

- instability in fronting beaches

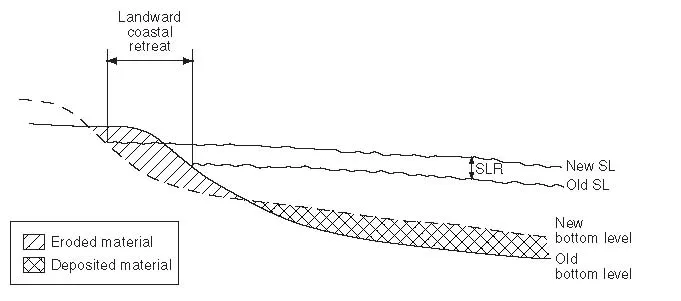

All of these factors will promote instability in the coastal system and therefore induce erosion as the system attempts to regain a form of dynamic equilibrium. Preventing a coastline being able to respond to sea level rise (SLR) is of paramount importance. In a world where many of our coastlines are experiencing this phenomenon, increased coastal instability will occur as the mean sea level increases. Of critical importance in this is a process referred to as ‘coastal squeeze’. This is explained in detail in connection with managed realignment (see Chapter 10); however, it is a problem which can affect all coasts. The Bruun rule of sea level rise (see Chapter 2 for full discussion) states that in order to maintain dynamic equilibrium under conditions of sea level rise, the equilibrium beach and nearshore profile needs to relocate upwards and landwards (Figure 1.1). Clearly this is unproblematic where lack of coastal development and an unprotected coastline occur, but where there are hard defences such landward movement is prohibited and the coastline cannot reach an equilibrium with the new sea level conditions. This is proving a major problem along many shorelines, not least because the inherent instabilities which result from the inability of coastlines to adjust to sea level rise are often manifest in loss of beach sediments, particularly important in tourist areas. Pilkey and Wright (1988) exemplify this process still further, and suggest that not only do sedimentary and floral environments become squeezed, but so do processes. During storms on undefended coasts, the surf zone widens in the landward direction. Where walls have been built, this landward extension may not develop fully, concentrating the greater intensity of surf zone processes into a confined area. This may help explain some of the observations of walled coasts, where sediment losses are greater during storms than on adjacent non-walled coasts. Indeed, Pilkey and Wright develop their argument with studies supporting the intensification of longshore currents, wave reflection, rip-currents, and pressuregradient related currents; all of these could be responsible for increased sediment losses from beaches fronting walls during storms.

The interaction of dunes and beaches is also important along wind-dominated coasts because it allows the beach to react to summer and winter wave regimes. These ideas are developed fully in Chapter 8 on dune building, but in this context, hard defences will prevent such sediment transfer to and from dunes. This means that during summer (calm) conditions, sediment transfer to dunes is prevented, while in winter, the supply of sand to the beach via draw down from dunes is also prevented; the result is that as beaches change towards their winter profiles, material to support this cannot come from the dunes, but comes from the upper beach instead. This is particularly critical in stormy periods, as there is no available sediment to source beach profile adjustments (Oertel 1974). This may then promote upper beach loss and eventual sediment starvation to upper beach areas. Similar problems also occur in barrier island settings, where over wash is critical in maintaining the stability of the barrier feature. In support of this, Inman and Dolan (1989) identified over wash as accounting for 39 per cent of shoreward sediment movement in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, this process being fundamental in maintaining barrier stability.

Figure 1.1 Simplified model of landward coastal retreat under sea level rise (Bruun rule). Note landwards and upwards movement of profile.

When dealing with cliffed coasts, the use of hard defences to prevent cliff erosion can be very effective. Although the processes are complex (see Chapter 5), the use of sea walls to stop cliff erosion is common. Regardless of technique, however, the fact that the hard defences are preventing any interaction between waves and cliff base means that erosion will stop — but, more critically, the input of cliff sediment to the coastal sediment budget will also stop, potentially leading to the loss of fronting beaches.

Contemporary coastal managers now have to address a legacy of coastal problems which have arisen following hard defence construction, largely as a result of coastal development which must be protected, even though it may not be built in places which are easily defended. Such problems often restrict best defence practice and prevent the ideal defence scheme being built. French (1997) highlights this problem with respect to nuclear power stations in the UK and shows that of the fourteen localities around the UK coastline where such installations occur, nine may have future defence problems due to low-lying land or coastal erosion. Clearly, such significant developments must be protected from any shifts in coastal position and, no matter what factors come into play with regard to coastal movements, these sites will need to be protected.

Historically then, contemporary coastal managers have been left with a legacy of erosion and defence construction which will be expensive to correct and maintain. The former belief that humans are the masters of the natural environment and that science will provide the solution to all problems was unfounded. The fact that this belief led people to build closer and closer to the coast has left many problems which can only really be solved by building hard structures to keep the sea out and by spending a lot of money. Clearly, this cannot happen indefinitely and so, in response, new ideas are starting to appear.

Recent trends in defence planning

When discussing coastal defence, several distinctions can be made. The term ‘coastal defence’ is a much used, but also much abused term for any feature along a coast or estuary designed to protect the hinterland. It is more correct, however, to distinguish between two forms of coastal defence. First, flood or sea defences are structures used to prevent the hinterland from being flooded by the sea, and thus refer purely to the prevention of inundation of the lan...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Tables

- Plates

- Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- Part I Introduction

- Part II Hard Approaches to Coastal Defence

- Part III Soft Approaches to Coastal Defence

- Part IV Coastal Defences in a Changing Environment

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Coastal Defences by Peter W. French in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.