Introduction

New university lecturers are not usually formally trained for teaching nor are they expected to have a teaching qualification. They do, however, possess a wealth of knowledge about education and its practices. All lecturers have spent a good portion of their lives as students, know what it is like to be taught and so have many ideas and examples of what they like and don’t like about teaching and learning. They remember their high-school teachers and university lecturers and know what was beneficial for them and also what did not help. This knowledge provides an idealized teaching model that can be a valuable starting position for learning to teach.

Personal experiences of being taught, however, are not enough in themselves. As they develop appropriate skills, lecturers also need to acknowledge the things they do well and what their limitations might be as they work out the full potential of teaching in practice. The new academic can reflect on images of teaching and try to model their disciplinary practices in this way; knowing what sorts of things they enjoyed and connecting teaching with the discipline and its particular knowledge forms. Past experiences must then become a part of an exercise in careful systematic reflection if these are to provide a more meaningful starting point for decisions about how and what to teach. This analytical process provides a useful foundation for practice and it is this type of personal inquiry professional programmes and workshops often support (in contrast to an expert telling academics what to do). The concept has many names and can be called researching one’s practice, practitioner research or simply research into teaching. The focus is always on the subject of a teacher’s learning.

A research approach to learning provides a level of academic and professional integrity and a clear strategy for the lecturer wishing to improve their craft, not just at the start but also throughout a career. New academics already have a measure of skill as researchers in their discipline and in this context are learners and knowledge creators. If they can think of their own teaching as a legitimate subject for study and use the same research skills to investigate this, then they create their own teaching knowledge.

An optimistic or idealistic view of the university might evoke an image of lecturers and students as learners at all times, in all activities, including research, service and teaching. Learning to teach in a university is about valuing the idea that teaching is an important component of academic work that merits and requires a similar investment in critical thought and action normally given to other parts of the job such as disciplinary research.

The case for researching one’s practice

Learning to teach in university is largely a process of trial and error as part of an informal academic apprenticeship. Institutions that offer professional development support provide short introductory or advanced postgraduate courses in teaching, and colleagues with more experience may provide help and advice. However, to a great extent teacher learning comes through carefully thinking about the experiences of practice. How did my class go today, what went well and what needs to change? These and similar questions are the mainstay of personal development and will remain so while university teaching is an individualistic and private activity.

It could be argued that trial and error has served universities well in the past and the potential of the lecturer to gradually build up expertise in this way should not be underestimated. However, this learning strategy tends to take considerable time and also limits what can be achieved. In our contemporary and complex, mass higher-education systems, for which society and most students pay considerable fees, there must be ethical concerns about how long it might take a lecturer to develop their teaching to an acceptable standard. A consequence of substandard teaching is that generations of university students receive a second-rate education while their teachers slowly improve. Should this be a concern to the profession, teaching development needs to start on day one of a new academic’s appointment.

In contrast to teaching, most university lecturers, at least within the research-led university sector, have undergone years of research training to attain a reasonable level of research skills. For example, they know how to design projects, handle theory and make judgements about evidence. These skills have been learnt within their preferred subject but much of this expertise can be transferred into other areas of knowledge, such as studying teaching practice. Yet accepting that teaching, or more specifically ‘one’s own teaching’, can be a subject for study, requires a shift in thinking for many academics.

The starting point for an inquiry into teaching may have roots in the introductory programmes universities offer new academics. Most courses I have come across are designed in a workshop mode with topics such as lecturing, small group teaching and assessment. Participants are asked to reflect on theory and connect new ideas to their own experiences and practice circumstances. These programmes are typically not discipline specific with lecturers from many fields taking part and sharing knowledge. Courses can, if done well, provide a positive start to a university career and also offer a foundation for further professional learning.

However, every lecturer’s practice is constantly changing and for most, becoming a skilled teacher is a continuous undertaking. Lecturers teach distinctive subjects and in ways that are quite unique to the individual. Many have a great deal of freedom to determine what their students learn and the complexity and range of practice situations requires constant attention for every teacher. Using research skills appropriately for an inquiry into practice ensures that any learning is timely, relevant and useful for the individual.

If it is accepted that learning to teach can be done through research then it must share the same characteristics of any other form of research. If research is ‘systematic inquiry made public’ (Stenhouse, 1981), then research into teaching will be organized and methodical with practical decisions based on the best evidence and data available. A teacher’s learning (the intended outcomes of a research inquiry) will be made known to peers in some way. Making this public provides an opportunity for the research and its claims to be reviewed. In doing so colleagues contribute to each other’s learning.

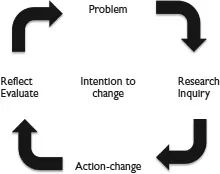

The idea of learning about one’s teaching practice through personal research has a long history that dates from the Action Research movement of the 1930s (Lewin, 1946) to more contemporary ideas about the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) (Boyer, 1990). Action Research is about identifying aspects of practice that need improving and then focusing on these through a systematic cycle of change, evaluation and then further change. Typically this activity will be action-orientated and focused on improving an identified problem:

Figure 1.1 The Action Research Cycle. A problem of practice is identified and this forms the basis of an inquiry. Action is taken after the results of the inquiry have been analysed and this is followed by an evaluation of the changes made. Any new problems are identified and these enter the next cycle of the Action Research project.

Action Research does not necessarily require a high level of research expertise and new academics without a strong background in disciplinary research can use it to change their practice. I would suggest that part of the inquiry process requires that published research and the theories of teaching are taken into account, and so skills in the critical review of primary and secondary sources of data are required to enhance the quality of the research cycle.

The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) came to prominence through the Carnegie Institute of America and its foremost advocate was Ernst Boyer (1990). Boyer brought the older medieval concept of the scholar up to date by suggesting that the idea of scholarship could be applied to all facets of our academic lives. The SoTL model proposes that we are scholars of research and so should be scholars of teaching. The values implicit in this work are congruent with my arguments for learning to teach by research. According to Boyer SoTL has four dimensions with the scholarship of:

- 1 discovery (creating new knowledge through discipline research);

- 2 integration (interpreting knowledge in and across the disciplines);

- 3 application (applying knowledge in service activities);

- 4 teaching (the study of teaching practice).

Boyer’s model has, however, been seen as unnecessarily complex and poorly understood (Boshier, 2009). Being ‘scholarly’ in teaching and learning is a concept not easily defined and many academics do not seem to connect with SoTL, possibly because of embedded ideas about the nature of the structure of academic practice and how we experience this as either research, or teaching or service.

SoTL has certainly not attained the widespread adoption that Boyer might have hoped for, although it has generated much debate and seems to have been a catalyst for Carnegie’s more recent promotion of the teacher as ‘inquirer’. Learning to be a teacher through ‘research into university teaching’ can simplify SoTL, if it is accepted that practice can be the subject of research. However, Boyer also wanted to raise the status of teaching in relation to disciplinary research but I do not think new academics need be overanxious about such value differences. Disciplinary research tends to have a higher status than teaching and is rewarded as such (Chapter 7). Yet this simple fact of academic life should not rule out trying to become the best teacher possible.

Sources of data

In any inquiry, whether or not it is Action Research, SoTL or a more general form of research into university teaching, there are similar steps in the process that include formulating a research question and gathering appropriate data. In addition, academics need to have some concept of what good teaching practice looks like.

The first exercise I give to new lecturers who take part in our introductory programmes is to ask individuals to think back to when they were students and identify one inspirational teacher. They then list that teacher’s qualities and, importantly, explain why they think such qualities were significant to them as learners. I have repeated this exercise on numerous occasions and what new lecturers have to say is repeated time and again. They have strong feelings about what a quality teaching and learning experience is and they are also very aware that attaining this in practice is not straightforward. A typical list of attributes collated during a group exercise includes:

Table 1.1 The qualities of an inspirational teacher: examples of responses collated between 2001 and 2010

| Characteristics of a good teacher |

|

High level of knowledge expertise Challenged thinking Explained complex ideas Knew each student Creative Enthusiastic Sense of humour Strict but fair Engaging Good communicator Good voice | Well organized Made it fun Respected an individual’s knowledge Showed humility Listened to what students had to say Showed genuine caring for student’s learning Rewarded student’s hard work Dedicated to discipline |

Sometimes I hear ideas expressed in different ways. For example, one academic described a good teacher as someone ‘you don’t want to disappoint’ and another said they needed to appear professional by ‘wearing a suit’. However, at a certain level there is general agreement on ‘what makes a good teacher’ and these qualities can provide an excellent starting position from which to develop a deeper understanding of practice. Be aware that most o...