![]()

1

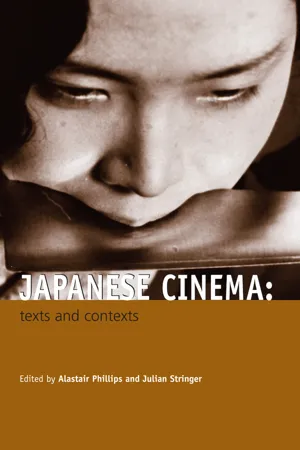

The Salaryman’s Panic Time

Ozu Yasujirō’s I Was Born, But … (1932)

Alastair Phillips

By the time that Ozu Yasujirō directed I Was Born, But … (Umarete wa mita keredo) in 1932, he had been working for Shochiku studios for almost a decade. His film went on to win a number of awards that year, including the prestigious Kinema Junpō First Prize, and it is remembered today as a moving, but also splendidly comic, film about the relationship between a Japanese white-collar office worker or ‘salaryman’ and his two young sons who on moving with their parents to a new house in the Tokyo suburbs have to learn about the disappointing social rules their father abides by. Ozu’s film remains an outstanding example of the director’s inflection of the ‘Kamata style’ which had evolved under the managerial guidance of the Kamata studio boss, Kido Shirō, in order to depict the experiences and concerns of Japan’s ordinary urban citizens as the nation underwent the convulsions and changes of modern life in the late Taishō (1912–1926) and early Shōwa (1926–1989) eras.

I Was Born, But … is an understated, but revealing, investigation of masculine identity, failure and what David Bordwell has usefully termed ‘the social use of power’ (Bordwell 1988: 224). It is also, as the film itself tells us, ‘A Picture Book for Adults’. If we take this latter formulation, we may identify a number of ways in which the film may be related to a discussion of the wider issues of gender, belonging and modernity identified two years previously in Sararīman kyōfu jidai [The Salalaryman’s Panic Time] – Aono Suekichi’s seminal contemporary analysis of the Japanese white-collar businessman’s malaise. Ozu’s film works in many ways as a fascinating compendium of images about modern life, especially in its treatment of the representation of class and social space. One can also see how the film’s picturing of the ordinary Japanese salaryman’s anxieties around industrialisation and social identity intersects with the development of the early Shōwa era’s Shinkō Shashin (New Photography) which attempted, in a similar fashion, to interpret the new cultures of city life and society from dynamic and innovative visual perspectives. These images (often collected in their own picture books) were attempts to record faithfully social change and then interpret this upheaval in terms of a newly mechanised mass culture. By looking at these developments in photography in relation to the film’s own visual and discursive strategies, particularly those concerning the construction of spectatorial knowledge specifically about questions of seeing, we may understand how I Was Born, But …’s careful narrative social concern works within a pictorial regime ideally suited to delineating the unease felt by the salaryman seen here, and elsewhere in contemporary Japanese culture of the time.

It is hard not to think of Ozu himself as a ‘salaryman’ who was to be employed by the same filmmaking corporation for most of his working life. Certainly, the nature of Shōchiku’s managerial and organisational structures confirms the notion that it was one of the pre-eminent sites from which Japanese mass culture engaged with changes in contemporary society. The company had originally become known for its involvement in popular theatre and had established filmmaking operations in 1920 with the appointment of the American-born son of Japanese immigrants, Henry Kotani. Ozu joined after an introduction by his uncle, and a year later, in 1924, the same year that the influential figure of Kido Shirō took over as head of Shōchiku’s Kamata studios, he was appointed to the rank of assistant cinematographer. By 1926, he had become an assistant director under the guidance of Ōkubo Tadamoto. Shōchiku, under the paternalistic guidance of Kido, who made several visits to the West Coast of the US during the decade, soon established a hierarchical set of production methods akin in part to the Hollywood studio system involving teams of trained cinematographers, scriptwriters, editors and publicists. A house journal, Kamata, evoked the evolving ethos of the warm-hearted, but also potentially socially acute, ‘Kamata flavoured’ shōshimin eiga (home drama of lower-middle-class people) and shomin eiga (home drama of everyday folk) which featured, like other Shōchiku genre productions, a rota of new and established stars and actors.

Despite the coincidence of this relationship between Tokyo and Los Angeles and the pervasive popularity of American cinema for mainstream domestic audiences, it is important to note that Ozu’s salaried existence within Shōchiku did not entail a wholescale replication of modern American production methods and ideologies. For one thing, as Hasumi Shigehiko has pointed out, in contrast to a competing company such as Tōhō who based their mode of production around the central figure of the producer, the studio actually favoured a more formalised ‘director system’. This allowed figures such as Ozu the means ‘to assemble a team of people for different, specialised fields of production and to cultivate them so they could continue to work together’ (Hasumi n.d.). Hence we see, throughout the director’s long career, the profound significance in terms of collaborative working partnerships of key figures such as the cinematographers Mohara Hideo and Atsuta Yūharu, the scriptwriter Noda Kōgo and the production designer Hamada Tatsuo.

Like Ozu himself, these fellow practitioners should not be seen as professionals keen simply to emulate the methods and forms of a dominant Western model of influence. The Japanese film industry needs to be observed within the historical context of its own contested and evolving relationship with the nation’s modernity and all its associated economic upheaval and dynamic social and industrial transformation. One way of thinking about this in more concrete terms would be to see I Was Born, But … as a text which, in terms of its production background and methods, is symptomatic of the very culture it seeks to represent on screen. Hence, as we shall see later, the nods the film makes towards its self-reflexive status as a distinctively modern text cunningly concerned with the fallabilities of the modern world and the means by which visual culture can transmit knowledge about the societies that inhabit it.

As Bordwell has convincingly argued, I Was Born, But … is a hybrid genre production which combines the sentimental appeal of the shōshimin eiga with the social commentary of the ‘salaryman film’ and the physical humour of the nansensu (nonsense) idiom so prevalent in Japanese mass culture of the period (1988: 14). Co-scripted by Ozu and Fushimi Akira, the film revolves around the decision of Mr Yoshii (Saitō Tatsuo) and his family to move to a new Tokyo suburb where the two Yoshii sons (Aoki Tomio and Sugawara Hideo) struggle to find acceptance within a group of neighbourhood boys who include the son of Mr Yoshii’s boss, Mr Iwasaki (Sakamoto Takeshi). The Yoshii children hold their father in high esteem, unaware of his vulnerability at work. After the screening of a home movie shot by Iwasaki, and projected in his wealthy residence to his employees and neighbours, the boys are forced to realise how fallible their father is when they see him ingratiating himself in public at the behest of his patron. Stunned, they react angrily towards their parents before learning to realise that subordination and duty are necessary within capitalist social relations and that their predicaments within the school and in play are only a prelude to the necessary compromises of modern adult life.

Ozu had already begun to delineate the milieu of the Japanese salaryman in films such as The Life of an Office Worker (Kaishain seikatsu, 1929), The Luck Which Touched the Leg (Ashi ni sawatta kōun, 1930), The Lady and the Beard (Shukujo to hige, 1931), and Tokyo Chorus (Tōkyō no kōrasu, 1932), and he continued to portray the various affective crises and entanglements of Japan’s white-collar classes in subsequent features such as Where Now are the Dreams of Youth? (Seishun no yume ima izuko, 1932) and the post-war successes Early Spring (Sōshun, 1956), Good Morning (Ohayō, 1959) and An Autumn Afternoon (Sanma no aji, 1962). What marks I Was Born, But … is its subtle, but nonetheless emphatic, questioning of the whole ethos of the system that supported the nation’s white-collar culture. This may well be due to the thesis advanced by Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano who claims that by the beginning of the decade in Japan ‘aspects of modernization such as capitalization, centralized political power, industrialization, propagation of rationalism and urbanism had reached their limits, and the conflict between classes, the widening of the local communities and their ethos, signalled the unfulfilled hopes of the modernization project. The films of Shochiku Kamata studios belong to this period and parallel the vicissitudes of Japanese modernity in crisis’ (Wada-Marciano 1998: 73). In other words, I Was Born, But …, despite its many humorous episodes, is marked by a sense of controlled despair about the price of social change. In constructing such a close analogy between the worlds of the children and the adults it may also be seen to be positing an argument about the future direction of Japan’s modernity.

To examine these issues in further detail, we should first look at the film in terms of its iconography and particular representation of class and space. Ozu’s film is marked by a distinctive sense of social stratification despite the fact that the generational gap between the children and the adults in the film is actually bridged by a comparative strategy which analyses the ways in which the social world of the children provides an echo and precursor of the ways in which the adult characters then lead their lives. There are three groupings which underline this point. At the core of the film are the tentatively mobile petit-bourgeois Yoshii family within which the sons first look up to their father’s lot in life, then reject it, then learn to consider its virtues despite the father’s forlorn admission to the mother that he hopes that neither of their sons will ‘become an employee like me’. Above them we see the casual professional and leisured affluence of the Iwasaki family which includes the smartly dressed son Tarō, a prominent member of the gang which taunts the Yoshii sons. Below them are the young sake seller and another blue-collar worker or tradesman and his son who is reduced to tears by the gang at one point.

To think of the subtleties of the dynamics of class relations in Ozu’s film, we need to consider the social and economic situation Japan was facing at this point in its history. By the early 1930s, the country, like many other industrialised economies, was well into a protracted period of economic depression which had been precipitated by a national financial crisis in 1927 only three years after a temporary post-earthquake reconstruction boom. The beginning of the Shōwa era in 1926 was thus marked by a growing sense of the fragility behind the dynamic, if uneven, process of modernisation which had characterised the preceding Taishō era. If in 1930 ‘one out of five non-agricultural male workers was a clerical employee in a firm or government bureau’ (Bordwell 1998: 34), in 1932, the year I Was Born, But … was made, one in five of all unemployed workers was a middle-class white-collar male (Schwartz 1999). The film thus portrays all the insecurities of a world in which its central male salaryman character is striving to construct a tentative domestic security for his family while simultaneously being beholden to an enterprise seemingly marked by inertia and deference. Aono Suekichi’s commentary in his publication The Salaryman’s Panic Time, published in 1930, the same year that Siegfried Kracauer’s analysis of the malaise of the German office worker, Die Angestellten, also appeared, thus seems particularly prescient. As Harry Harootunian argues, Aono’s work sought to analyse ‘the social structure of the salaryman’s class… within the larger context of capitalist social relations in order to explain how and why they were fated to a life of continued unhappiness and psychological depression caused by the growing disparity between their consumerist aspirations and their incapacity to satisfy them’ (Harootunian 2000: 202). The ‘panic’ that Aono’s text referred to was the abiding sense of ‘both a diminution of [the salarymen’s] social position and the disappearance of the culture they had once known’ (208).

This sense of being locked into an inevitable and potentially regressive working adulthood is vividly portrayed in I Was Born, But … in the famous...