- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Museums, Society, Inequality

About this book

Museums, Society, Inequality explores the wide-ranging social roles and responsibilities of the museum.

It brings together international perspectives to stimulate critical debate, inform the work of practitioners and policy makers, and to advance recognition of the purpose, responsibilities and value to society of museums.

Museums, Society, Inequality examines the issues and:

- offers different understandings of the social agency of the museum

- presents ways in which museums have sought to engage with social concerns, and instigate social change

- imagines how museums might become more useful to society in future.

This book is essential for all museum academics, practitioners and students.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Museums and society: issues and perspectives

1

Museums and the combating of social inequality: roles, responsibilities, resistance

Richard Sandell

Museums and galleries of all kinds have both the potential to contribute towards the combating of social inequality and a responsibility to do so. Though by no means entirely new,1 such claims to social influence and agency are still likely to elicit challenges from both within and outside the museum. Within the museum and wider cultural sector, there are many who remain uncomfortable with the assignment of overtly social roles; roles that are perceived as imposed, extraneous and unnecessary. For the majority of those working in social, welfare and health agencies – those whose day-to-day work is concerned with issues of inequality and disadvantage – museums’ roles in terms of education and leisure are more likely to be acknowledged than their potential contributions to social equity. Museums are viewed as unlikely partners2 whose goals are discretely cultural rather than social.

Claims to social agency – the ability to influence and affect society – may not be new, but in recent years these are taking on both a new form and a new confidence. First, claims are moving from the more abstract, theorised and equivocal to become more concretised and more closely linked to contemporary social policy and the combating of specific forms of disadvantage. For example, whilst there has been a burgeoning literature that explores the political effects of representation and the generative potentials of culture, this has focused largely on processes of construction within the museum, rather less on processes of reception and the tangible impact on audiences.3 Here, the social impact of the museum is linked to outcomes such as the creation of cultural identity or the engendering of a sense of place and belonging (as well as negative outcomes such as the subjugation of minorities). These complex outcomes that are difficult to measure have been based, for the most part, on theoretical assumptions around the signifying power of culture. Alongside increasingly sophisticated conceptual development in the area of representation there are now increasingly bold and explicit claims that are beginning to explore the museum’s impact on the lives of individuals and communities and the role that cultural organisations are playing in tackling specific manifestations of inequality – such as racism and other forms of discrimination, poor health, crime and unemployment.4

Second, within the cultural sector, fundamental questions about the social purpose and role of museums and galleries, that have for many decades been marginalised, have more recently been foregrounded and have achieved a currency and confidence that has proved difficult to ignore, even by the most entrenched and traditional sections of the museums and arts community.5 Those who work within and with museums and those who fund and support them are increasingly asking: What kind of difference can museums make to people’s lives and to society in general? What evidence exists to support this view?

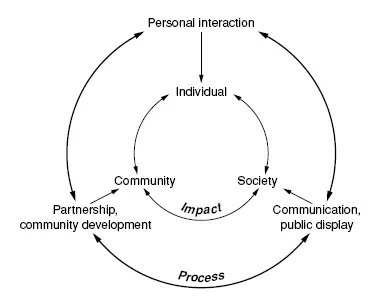

This chapter draws on recent empirical and conceptual research to posit a framework within which the social agency of museums can be further explored. It argues that museums can contribute to the combating of the causes and the amelioration of the symptoms of social inequality and disadvantage at three levels: with individuals, specific communities and wider society. It is recognised that the arguments are presented from a British perspective, though examples of museum initiatives in Australia and the US are cited. The concepts discussed and the conclusions reached are by no means confined to the British context. It is then argued that, whilst not all organisations have the resources or the mandate to deliver benefits at all three levels, nonetheless, all museums and galleries have a social responsibility. The argument for acknowledgement of a social responsibility emerges from discussion around the interplay between the notions of social inequality6 and cultural authority.7 The chapter concludes by suggesting that all museums have an obligation to develop reflexive and self conscious approaches to collection and exhibition and an awareness and understanding of their potential to construct more inclusive, equitable and respectful societies.

Museums and inequality: roles and outcomes

In what ways can museums engage with and impact upon social inequality, disadvantage and discrimination? The framework posited below (see Figure 1.1) has emerged from recent conceptual and empirical research and a range of international and UK examples are presented to illustrate the roles described.8

The framework suggests that museums can impact positively on the lives of disadvantaged or marginalised individuals, act as a catalyst for social regeneration and as a vehicle for empowerment with specific communities and also contribute towards the creation of more equitable societies. It is this latter role that will receive greatest attention here, as it is argued that it is through the thoughtful representation of difference and diversity that all museums, regardless of the nature of their collections, the resources available to them, their mission and the context within which they operate, can contribute towards greater social equity. The framework purposefully challenges the notion that the museum’s contribution to the combating of social inequality is confined to its outreach or education work with specific groups and communities. It attempts to illustrate the wide-ranging outcomes museums can deliver and the most commonly deployed means or processes through which these are achieved. It is, however, necessarily schematised and it is recognised that, in practice, the categories of impact and process are neither so distinct nor discrete.

Figure 1.1 Museums and the combating of social inequality: impact and process.

Individual

This category concerns the impact that museums can have on the lives of individuals. Here the potential outcomes are wide-ranging, from the personal, psychological and emotional (such as enhanced self-esteem or sense of place) to the pragmatic (such as the acquisition of skills to enhance employment opportunities).9 In some instances, these outcomes are unintended, peripheral or at least are not always articulated within the goals of the museum or specific programme. For example, projects that may be motivated at the outset by a desire to encourage members of a specific group, under-represented in the museum’s visitor profile, to make use of its services, have later resulted in unexpected positive outcomes for individuals (Sandell 1998). In such cases, the impact on individuals’ lives may only emerge informally through anecdote or remain undisclosed or unevaluated. In recent research undertaken into the contribution of large local authority museums to social inclusion, one gallery described a project with visually impaired and blind people:

The visually impaired group – now just a group of friends – have real rapport with staff and feel at home in the building. One blind person told us how she learned to handle public places through coming to the museum, which took her out of her shell. You only get that kind of feedback from individuals themselves, as evidence from group leaders is always second hand. I hope we are doing that for others too.

(GLLAM 2000: 25)

Another project at Nottingham Museums initially sought to enhance access to its programmes and facilities for users of mental health services in the city (Dodd and Sandell 1998). Over time, the partnership between the museum and the health service developed to include new goals, based around using the museum programmes as a vehicle to deliver skills and confidence that would enhance the quality of life for individuals.

In other instances, museums are purposefully designing programmes that position access to, or use of, the museum, not as a goal in itself but as the means of helping to bring personal and practical benefits to individuals. Though the exact nature of that benefit or outcome is not always known at the outset, crucially the programmes are developed with a focus on bringing benefit to the individual and enhancing their quality of life, rather than the museum.10 Such programmes reflect a belief in the social utility of museums.

An example can be found in the training projects established by the Living Museum of the West, Melbourne, Australia. The museum has provided the setting for a number of projects that have sought to provide training for longterm unemployed people:

In Australia, such job creation schemes have frequently been criticised as merely providing cheap labour pools, and for failing to deliver meaningful long-term benefit to the participants . . . However, for the Living Museum of the West, such schemes offer an opportunity to provide valuable training and skills development for local people, in particular those from disadvantaged groups with few opportunities to gain employment . . . For example, the Koorie Garden Project . . . aims to provide culturally relevant employment for indigenous people within the locality combined with horticultural training. The project enables the participants . . . to develop skills to help them gain employment after the lifetime of the project. The original members of the Koorie Garden Project have now moved on to form a separate company in which all participants are shareholders and run a gardening business within the region.

(Sandell 1998: 413)

Finally, recent research into the role that small museums can play in relation to social inclusion highlights the potential significance for some individuals of voluntary work.

The research [also] highlighted the significance of volunteering as a means by which individuals gained benefit. At the Ragged School Museum in London, volunteers come from many backgrounds and for many reasons. As well as benefiting the museum, volunteers can also gain. Through volunteering, unemployed people can learn new skills, people with mental health problems learn to develop confidence and elderly people can develop a social network and combat isolation and loneliness.

(Dodd and Sandell 2001: 27)

The processes by which these individual outcomes are delivered are, for the most part, characterised by face-to-face interaction between museum staff or representatives and members of, for example, a community group. In larger museums, they are often developed by the museum’s education or outreach section. In many instances the most effective of these are developed in partnership with the agencies that have direct links with, and knowledge of, the group with which the museum is engaged (Silverman 1998).

Community

What role can museums play in delivering benefits to specific, geographically defined communities? Within this category we might consider museums’ contributions to regeneration and renewal initiatives in, for example, deprived inner city or rural neighbourhoods. Specific outcomes include enhanced community self-determination, and increased participation in decision-making processes and democratic structures. Though empirical data is limited, it appears that cultural organisations, in comparison with other agencies, might be uniquely positioned to act as catalysts for community involvement and as agents for capacity building. An international conference on the role of culture in regeneration initiatives concluded that: ‘Cultural initiatives are inclusive, and have an unsurpassed capacity to open dialogue between people and engage their enthusiasm and commitment to a shared redevelopment process.’ Furthermore, ‘culture and the development of creativity has a major part to play in helping to develop the capacity of local communities to address their own needs’ (Matarasso and Landry 1996: v).

Although little formal evaluation of the museum’s role in community empowerment and capacity building has been undertaken, those project experiences that have been documented point to the potential for museums to engage and enable groups that have previously been deprived of decision-making opportunities. Museums have provided an enabling, creative, perhaps less threatening forum through which community members can gain the skills and confidence required to take control and play an active, self-determining role in their community’s future. Nancy Fuller, in her account of the Ak-Chin Indian community’s ecomuseum project, provides further insight into the specific role that museums can play and the methods and techniques they can employ in empowering a community. She suggests that the ecomuseum model offers,

a new role for community museums: that of instrument of self-knowledge and a place to learn and regularly practice the skills and attitudes needed for community problem solving. In this model the museum functions as a mediator in the transition from control of a community by those who are not members of the community to control by those who are.

(Fuller 1992: 361)

In the categories of individual and community impact outlined briefly so far, the role of face-to-face engagement, partnerships with non-museum agencies and approaches and working practices that might be likened to those used by, for example, social, health or community development workers can be identified. This perhaps goes some way to explaining the perception that the museum’s role in combating social inequality is equated solely with the outreach and education function. Furthermore, this may also account, in part, for reticence and resistance on the part of some museums’ staff who feel that they are ill-equipped to embark on projects of this kind, lacking the skills and resources to work directly with communities.

However, what role might museums play in tackling inequality through their ubiquitous and long-established functions of collection and display? The growing body of literature that explores the generative potential of museum representations focuses largely on its negative consequences and the museum’s part in excluding, stereotyping or silencing difference through the selection, arrangement and public display of objects. In what ways then are museums reversing processes of exclusion and othering, to include and to celebrate, rather than stereotype, difference? Where this is happening, what impact does it have on the perceptions and actions of those who visit and on the creation of more equitable, tolerant societies?

Society

Claims that museums can change society can appear inappropriately immodest and naïve, a sentiment reflected in Stephen Weil’s cautionary scepticism.

Museums might [also] be more modest about the extent to which they have the capability to remedy the ills of the communities in which they are embedded. We live, all of us, in a society of startling inequalities, a society that has badly failed to achieve community, and a society that seems determined to lay waste to the planet that is its sole source of support. Museums neither caused these ills nor – except for calling attention to them – have it within their power alone to do very much to cure them.

(Weil 1995: xvi)

Indeed, it is problematic to establish a direct, causal relationship between museum practices and contemporary manifestations of social inequality or their amelioration. On the other hand, museums and other cultural organisations cannot be conceived as discretely cultural, or asocial – they are undeniably implicated in the dynamics of (in)equality and the power relations between different groups through their role in constructing and disseminating dominant social narratives. What then of the political role that museums might play, alongside other organisations within civil society,11 in promoting equality of opportunity and pluralist values?

Constructing equality

The ways in which objects are selected, put together, and written or spoken about have political effects. These effects are not those of the objects per se; it is the use made of these objects and their int...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Museums and Society: Issues and Perspectives

- Part 2: Strategies for Inclusion

- Part 3: Towards the Inclusive Museum

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Museums, Society, Inequality by Richard Sandell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.