- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Techniques of Archaeological Excavation

About this book

Immediately hailed as the standard work and one of the most widely used archaeological field manuals, this survey of current excavation techniques, now in its third edition, remains an in-dispensible guide for archaeologists. his text has been written by an experienced excavator about the inadequacies of excavation techniques and the possible ways of refining them and should serve as a valuable introduction to the subtleties and spirit of modern archaeology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Techniques of Archaeological Excavation by Philip Barker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: the Unrepeatable Experiment

Excavation recovers from the earth archaeological evidence obtainable in no other way. The soil is an historical document which, like a written record, must be deciphered, translated and interpreted before it can be used. For the very long prehistoric periods of human history excavation is almost the only source of information and for the protohistoric and historic periods it provides evidence where the documents are silent or missing. The more, therefore, that we can refine our methods and techniques the more valid will be the interpretations which we derive from our results.

This book does not pretend to be the Compleat Excavator. It does not describe the way to dig every variety of site on every kind of subsoil. But it is written as the result of hard thinking, in the field and at the drawing-board, about the inadequacies of our excavation techniques and the possible ways in which we might refine them. However, each refinement will produce more complicated evidence, which, in its turn, will bring greater difficulties of observation and recording, more data to be sorted, more intricacies to be interpreted and more detailed plans and sections to be published. Yet, however complex and detailed excavations become, we must always keep the wholeness of archaeology in mind. Excavation is only a method of producing evidence about the past, a means to an end, akin to surgery in that it is drastic, unlike surgery in that it is always destructive.

The whole of our landscape, rural and urban, is a vast historical document. On its surface has accumulated a continuous accretion of hundreds of thousands of small acts of change, both natural and human. The purpose of excavation is to sample the sequence and effect of these surface changes at a chosen point. Such samples will, inevitably, always be very small since even the largest excavation covers only a tiny fraction of the landscape it studies. The point chosen will ideally be one which promises to give the maximum information about the things in which we are interested: periods of occupation, types of structure, burial practices, a social unit, past environments or, happily, all of these and more on one site.

Every archaeological site is itself a document. It can be read by a skilled excavator, but it is destroyed by the very process which enables us to read it. Unlike the study of an ancient document, the study of a site by excavation is an unrepeatable experiment. In almost every other scientific discipline, with the exception of the study of the human individual and other animals, it is possible to test the validity of an experiment by setting up an identical experiment and noting the results. Since no two archaeological sites are the same, either in the whole or in detail, it is never possible to verify conclusively the results of one excavation by another, even on part of the same site, except in the broadest terms, and sometimes not even in these.

In the case of an urban excavation it may be feasible to confirm a defensive sequence or the broad stratigraphy revealed on one site, by excavation on another nearby, as equally it may be possible, on a site in which a sequence of stone buildings has been preserved after excavation, to re-examine the evidence as one would a written document. But generally excavation is destruction and often total destruction. Our responsibility therefore is very great. If we misread our documents as we destroy them, the primary evidence we offer to those interested in the past will be wrong and those following us will be misled but will have no way of knowing it.

The excavator’s task is to produce new evidence that is as free as possible from subjective distortions and to make it quickly and widely available to other specialists in a form which they can use with confidence in their own research. This, however, is not enough. There is an increasing number of people who take a highly intelligent interest in the past. To these, the results of excavations and the integration of these results into local, national and continental history must be presented in different, but equally valid, forms, such as museum displays, synoptic books, lectures, television and radio programmes.

One of the tasks of the historian and the archaeologist is to modify our view of the past by continual reconsideration of the evidence and, in the case of the archaeologist particularly, the production of new evidence. For the many thousands of years before the invention of writing and the first surviving documents, whether in stone or clay or papyrus, archaeological evidence is all we have. Increasingly in later centuries, documentary evidence must be married to the archaeological evidence, which is continually expanding in scope and complexity. By contrast, it is unlikely that there are many ancient manuscripts left to be discovered. Inscriptions will be dug up from time to time, some more Dead Sea scrolls may be found, and, like the Haydn Mass recently discovered in Ireland, a precious manuscript may be waiting to be revealed, but there is little doubt that, in the future, new information about the past will derive chiefly from archaeology and from fieldwork, and excavation in particular. The purpose of excavation is therefore to solve, or at least to throw light on, problems which can be studied in no other way, since there is an absolute limit to the amount one can learn from an archaeological site by looking at it, walking over it, surveying it, or photographing it from the air, just as there is a limit to the inferences which can be drawn from documentary references (where they exist) to archaeological sites. Only excavation can uncover a sequence of structures or recover stratified and secure dating evidence, or the mass of environmental or economic evidence which most sites contain.

The multiplicity of disciplines which go to make up modern archaeology combine to study every aspect of the lives of early peoples—their environment, their trade, their diet, the rise and fall of individual settlements and groups of settlements, their cultural affinities, the influences which shaped their buildings and their art—to look beyond the objects and the debris of everyday life to the thoughts that lay behind them, and the intentions that produced them. The chief function of the excavator is, therefore, to produce primary evidence of as high a quality as possible for the use of other archaeologists, historians, and all those whose interest lies in understanding the past.

This evidence, and the reasoned deductions which can be drawn from it, using all the parallel evidence from other sources, documentary, linguistic, scientific, epigraphic or whatever, enables us by acts of sober imagination to recover fragmentary glimpses of the past, like clips from an old silent film, badly projected.

Slowly we are building up a fuller and more accurate edition of the film. It will never be complete, and like any film will always be subject to the distortions of cutting and editing, and the viewpoint not only of the director but of the audience. Our task is to minimize the distortions, to bring into focus the unclear images and to discern the converging patterns which over the last fifty millennia have brought us to the point where I write, and you read, this book.

2

How Archaeological Sites are Formed

It is much easier to understand the evidence recovered from excavations if we appreciate the ways in which archaeological sites are formed: how a castle becomes an earthwork, or a Roman town a field of corn; how a prehistoric village becomes a series of dark green lines seen only in the spring—though not every year; and how a modern city’s past can be buried under tons of concrete yet still be recovered.

The surface of the earth is almost entirely covered by soil which derives from the underlying bedrock, be it sand, gravel, chalk, granite, clay or any other rock, hard or soft. The nature of the soil cover is determined, therefore, by the rock on which it lies, and this, combined with the drainage of the subsoil, will in turn determine the fertility of the soil, which, in its turn will influence the patterns of vegetation, of farming and of settlement.

Archaeological sites are merely the residues of settlements and structures, reduced to rubble and earthworks by decay, erosion, stone-robbing and the invasions of plant and animal life. Even in temperate Britain the ‘jungle’ returns with astonishing speed to an abandoned garden or neglected copse. Bombed sites in city centres were colonized within a few months, and there are places known to the writer where almost impenetrable woodland cloaks ruined cottages inhabited only half a century ago. Stone buildings, even deeply robbed ones, leave more evidence of their presence than wooden ones, which may be reduced to no more than a line of dark pits, or barely discernible discolorations of the soil, or concentrations of stones.

In order to interpret the evidence which we uncover, we need to understand as fully as possible what happens to a building when it is abandoned or is pulled down, and what happens to rubbish when it is thrown into a pit or spread as manure on the fields. We need to know how ditches and pits silt up and how banks and mounds erode, as well as something of the action of the soil on organic materials from leather and cloth to human bodies.

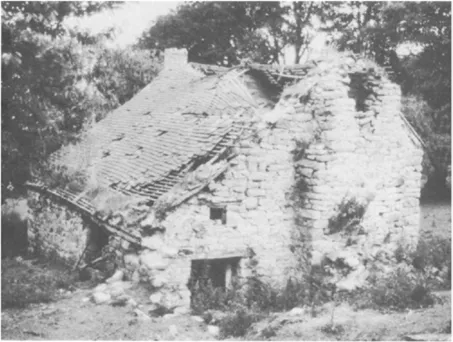

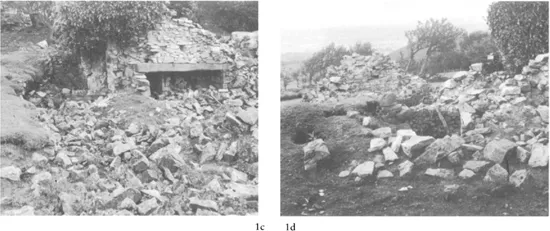

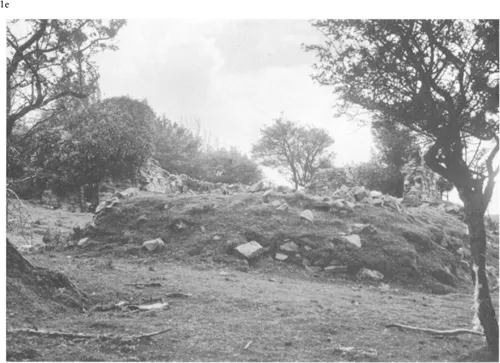

It is illuminating to observe what happens to a derelict building over a period of years, or the way in which plants invade an unused path, or a disused railway. Sometimes it is possible to find a recently abandoned settlement which is on its way to becoming an archaeological site and to observe the processes of regression at work. Because of the more intensive agriculture and redevelopment of the lowlands, such sites are more often found in hill country. One such is illustrated in Fig.1. The processes of destruction and decay which transform structures into the archaeological features which we excavate are perhaps best illustrated by simple examples which can, as it were, be multiplied up into the highly complex series of interrelated components which make up most archaeological sites. Some of the commonest features found on excavations are illustrated later in this chapter.

The other factor of major importance in the understanding of the formation of archaeological sites and their unravelling by excavation is the theory of stratification. This derives originally from the realization by geologists that those rock strata which lay uppermost were later in date than those which lay below them. In its simplest form it is easy to see that layers deposited on the bed of the sea are formed later than the rocks beneath or that a sheet of lava is later than the moutainside on which it lies. But the earth’s surface is not static—rocks are thrust up through overlying layers; erosion removes upper layers, exposing the rocks beneath; sometimes gigantic folds seem to reverse the proper order. Yet in all these cases the sequence of events can be understood—the intrusive rocks can be seen to be earlier, though the upheaval which caused them to become visible is later; the process of erosion is later than the rock it exposes and the folding which turns the layers upside down presents a stratification which might be misleading if it were not realized that folding had occurred.

It is the same with archaeological sites. This is most easily demonstrated by a series of superimposed floors, where it is obvious that the lower ones must be earlier. Similarly, if a roof collapses on to the uppermost floor, and the walls then fall in on top of the fallen roof, the sequence of events is again obvious and will be revealed when the layers are excavated in the reverse order to the sequence of events. The construction, abandonment and decay of a simple stone building are shown in Fig. 2, 1–9. These examples could be extended to cover every possible situation met with on an archaeological site. Stratification can be defined, therefore, as any number of relatable deposits of archaeological strata (from a stake-hole to the floor of a cathedral) which are the result of ‘successive operations of either nature or mankind’ (Harris 1975, 100). Stratigraphy, on the other hand ‘is the study of archaeological strata…with a view to arranging them in a chronological sequence’ (Harris, ibid.).

1 a-e The way archaeological sites are formed. At Blakemoorgate on the northern end of the ridge known as the Stiper Stones in Shropshire, lies a deserted settlement. The remains of houses and outbuildings are contained within paddocks whose layered hedges have grown into trees, and the drove roads on each side of the site are overgrown with grass and gorse.

Since the site was deserted gradually, eventually leaving only one occupied farm, which was abandoned in the 1950s, the whole process of collapse and decay can be seen, from the empty farmhouse still with its roof, 1a, to a mound of stones and earth, 1e, the site of a desertion of perhaps a century ago. Such a site deserves detailed survey repeated at intervals to chart the processes of decay, and the recording of the memories of people, still alive, who knew it, before it goes back into the hillside.

How post-holes are formed

Many timber buildings are based on posts set into the ground (rather than standing on the surface—see Figs 3–6). In the majority of cases, a pit is dug to the required depth and the post inserted (Fig. 3); the post is sometimes set against the side wall of the pit, sometimes centrally. In either case the remaining space in the pit is backfilled with the earth taken out of it, or with stones or rocks. When the building is abandoned the post can disappear in a number of different ways:

1 It can be removed. In this case it may be possible to see that it has been rocked backwards and forwards in order to loosen it to make removal easier. The hole thus left may be deliberately backfilled with earth in order, perhaps, to remove a hazard, or it may simply be left to fill up naturally. It should be possible for the excavator to tell the difference. The deliberate filling is likely to be coarser and contain stones, and perhaps pottery or other artefacts, rather than fine silty material which has been carried by rain or wind or worm action. However, as wi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Illustrations

- Preface to the First Edition

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the Third Edition

- 1: Introduction: The Unrepeatable Experiment

- 2: How Archaeological Sites Are Formed

- 3: The Development of Excavation Techniques

- 4: Pre-Excavation Research

- 5: Problems and Strategies

- 6: The Processes of Excavation

- 7: Rescue and Salvage Excavation

- 8: Recognizing and Recording the Evidence

- 9: The Recording of Pottery and Small Finds

- 10: The Interpretation of the Evidence

- 11: Scientific Aids

- 12: Synthesis: The History of the Site

- Glossary

- Bibliography