![]()

The discourse of advertising

Advertising is the rattling of a stick inside a swill bucket

George Orwell (1936)

Introduction

Well, how would you define advertising? And what exactly counts as an advertisement? Most dictionaries focus primarily on its function as a public notice or announcement, but the art of advertising clearly extends much further than this. In our everyday lives we meet advertising in many forms, from the well-known media of press promotions, television commercials or billboard posters, to the less obvious devices of advertorials, product placements, event sponsorships, junk mailings or carefully staged large-scale public relations exercises — all, incidentally, requiring very much more time and effort (and language) than is needed by Orwell’s swineherd calling his pigs to the trough.

Some advertisers choose to address us with direct or hard-sell techniques, while others send us messages which are far more indirect, subtle or even subliminal. There is a trend at the moment, for example, for record companies to pay buskers in busy underground stations to perform acoustic versions of the label’s latest releases: the hope is that commuters will find themselves humming the tune on the way home and so be motivated to buy the record. Are the record companies really advertising here? There is some debate about this tactic: detractors call it stealth marketing; proponents liken it to the viral buzz of internet-led promotions, and indeed many are forecasting that the advertising industry is about to change dramatically along these very lines. Either way, the process certainly accords with Leacock’s (1924) famous definition of advertising as ‘the science of arresting the human intelligence long enough to get money from it’.

It goes without saying that the power of advertising is immense — as is the time, money and skill that goes into it. Producers of commercial goods and services routinely pour vast sums into promoting their wares through the advertising media, knowing that a successful campaign can win them vital market share and that failure to advertise effectively can have devastating results on the bottom line and the share price. The stakes are high: advertising agencies command steep fees and a successful brand manager is one of the hottest properties a business can have. Advertising is widely regarded as the driving force behind our consumerist culture; so much so that it is plausibly credited with having kept Western economies growing and thriving over the last 50 years.

The function of advertising, of course, is promotional: to draw to our attention and keep in our minds the availability and desirability of a product, service or brand. In order to achieve this function it must first reach its target audience, then capture that audience with a message that is both attractive and memorable. At its best it is a stunningly powerful means of communication, every bit the equal of any popular hit in modern music or film (indeed, advertising mixes with both these genres in a highly interactive way), and truly classic advertisements rightfully take their place at the cutting edge of modern art.

My own favourite advertisement never appeared on the TV or in the press and would never have won any prizes as a work of art. Nevertheless, it had all the essential qualities of a great ad: it alerted the audience to the availability of the product and emphasized its desirability and value. It was the call of a market trader in West London, selling slightly overripe bananas at the end of the day: ‘Come and get ‘em! The ones with the spots are the ones with flavour. Your money saver.’

Exercise 1a

Examine the following 1960s advertisement for Coca-Cola (© Coca-Cola] and consider what makes it such a typical example of advertising discourse.

• What is the overall tone of the advertisement? If the campaign were running on TV, what sort of voice would you expect to be hearing?

• Examine the words used in the copy. How carefully do you think they have been chosen? How innovative are they?

• What do you notice about the grammatical structure of the sentences?

• Who is the advertisement addressed to?

• What is they key message of the advertisement?

Sound, words and sentence structures, together with the construction and manipulation of meaning will be key themes in our analysis of advertising discourse. Consider your answers to the above questions as the chapter develops.

Much — though by no means all — of the power of advertising derives from language. In no other field (apart from poetry, perhaps) is so much creative energy put into producing so few, carefully chosen words. Slogans, catchphrases, jingles and puns are crafted with such skill and cunning that, while deconstructing a piece of advertising copy can sometimes look embarrassingly like literary criticism at its worst, it is hard to overstate the forethought that will have gone into constructing it in the first place.

No one would pretend that advertising slogans or catchphrases will pass into everyday usage in the same way as phrases from the Authorized Version of the Bible or Shakespeare’s plays have done.When they do, however, all the more credit is due to the copywriter, for we can safely assume that the inspiration will not have come from the contemplation of divinity or through the graces of the Muse; he or she has probably had to conjure a little gobbet of eternity from something far more mundane.

Be they ever so humble, phrases such as ‘your flexible friend’, ‘naughty but nice’ (coined by Salman Rushdie, no less), ‘it’s the real thing’, ‘stop me and buy one’, ‘hello, boys’ and ‘say it with flowers’ have all passed into British vernacular from advertising copy. Thus, just as John Mortimer’s civilized barrister Rumpole delights in quoting from the Bard and the Bible, so too in John Sullivan’s Only Fools and Horses wheeler-dealer Derek ‘Del Boy’ Trotter delights in serving up advertising straplines: his ‘you know it make sense’ and ‘a little dab’ll do ya’ were originally slogans for road safety and hair cream ads, respectively. Del Boy’s most characteristic catchphrase, ‘lubbly jubbly’ (normally uttered when easy money is in sight) even includes the name of the product: Jubbly was an orange drink sold in the 1950s in a triangular carton. The original slogan, ‘Lubbly Jubbly’, for reasons we will see as this chapter proceeds, is a beautiful example of the technique of crafting a wordmessage for an advertisement.1

At this point we should note again that language is by no means the only tool in the advertiser’s locker. Indeed, sometimes it is barely needed at all: ads for fashion houses, for example, will often feature only a carefully crafted visual, accompanied by a discreet name or logo. Occasionally a brand’s logo becomes so well known that it enables us to identify the company without any linguistic clue. See, for instance, how many of the logos you can recognize in Figure 1.01 overleaf.

Fig. 1.01 Famous logos

How well did you do? If you recognized several, you might like to consider that it is still relatively rare for a successful logo to be entirely without any linguistic suggestion as to its reference. The Apple and Shell logos depicted are, most obviously, an apple and a shell themselves; the Diners Club and Ericsson devices are based (though fairly abstractly) on the initial letters of the companies concerned; as a clue at least to the product being advertised, the Michelin man is wheeling a tyre, the Bic boy is holding a pen, the HMV dog is puzzling over a gramophone; more abstruse, perhaps, but the Nestlé picture features a nest, and the Johnny Walker figure is striding and carrying a walking stick; finally, the Yellow Pages logo is normally printed yellow in colour. Nevertheless, Citroën, HSBC, Mercedes, MSN and Renault do have logos that are genuinely language-free. If you identified these correctly, then you are in part attesting to the talents of the brand managers involved.

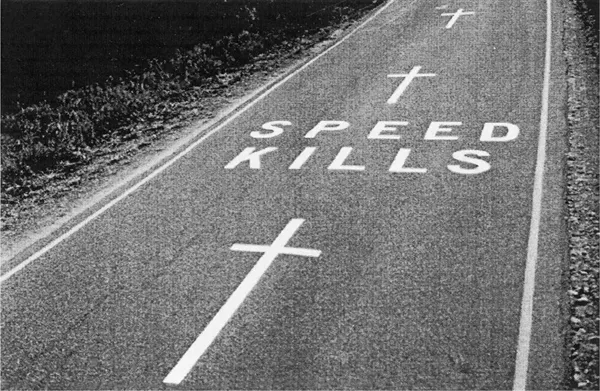

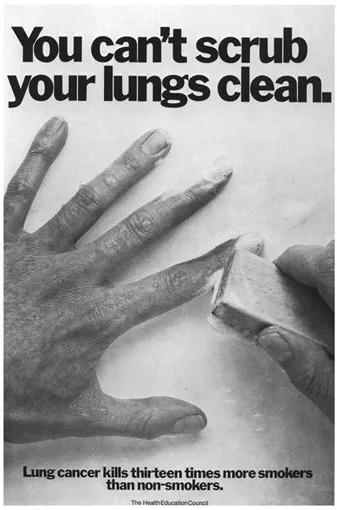

Logos, pictures and visual displays are an integral part of almost all advertising above the level of the newspaper small ad; and of course music is a fundamental and often indispensable element in many broadcast advertisements. While this chapter will naturally focus on the language of advertising, it is nonetheless important to understand that advertisers use language in synchrony with many other forms of communication in conveying meaning in their messages. Often there is an extremely strong relationship between the pictures used and the language employed. In Figures 1.02 and 1.03, designed and distributed in Britain in 1971 and 1994 by one of the world’s most prestigious advertising agencies (Saatchi and Saatchi), the impact of the message derives from and relies on the relationship between language and picture, and it would be more or less impossible to explain the significance of either in isolation.

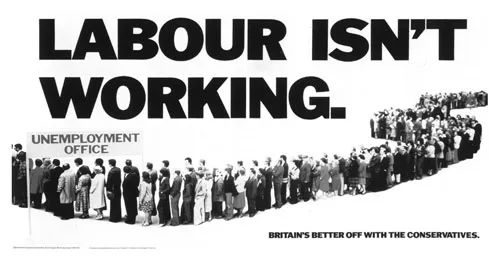

This is a convenient point at which to remind ourselves that not all forms of advertising are aimed at simply selling commodities. The Saatchi ads are examples of ‘social advertising’ — campaigns that encourage us, for instance, to give up smoking, avoid speeding or donate money to charitable appeals. Saatchi was also responsible for Figure 1.04 on p. 7, a political ad from the late 1970s.

Advertising, in one form or another, has been a key weapon in the armoury of politicians for a considerable time, and not necessarily in its most obvious form. Many branches of the press and broadcasting media, in spite of their protestations of independence, operate as mouthpieces for a particular political viewpoint — usually, as it happens, a viewpoint from which certain commercial interests (often their owners) are likely to benefit. The financial structure of almost all press and broadcasting enterprises, it should be remembered, is intricately and inextricably bound up in the advertising revenues they receive from national and multinational companies. Indirectly, then, political groups depend on these commercial interests for an important media channel, and the support of commercial media groups can be vital. John Major’s Conservatives retained power in Britain at the 1992 general election, against all the pundits’ predictions, benefiting enormously from a polling-day headline in The Sun attacking Labour. It was no handicap either that their advertising agency was Saatchi and Saatchi. Politics, commerce and advertising may be strange bedfellows, but they do seem to sleep together fairly regularly.

Fig. 1.02 Anti-speeding campaign. © Saatchi & Saatchi

Fig. 1.03 Anti-smoking campaign. © Saatchi & Saatchi

Fig. 1.04 Conservative election campaign 1970s

With so much at stake, government advertising, like commercial advertising, sometimes needs to be extremely subtle. After all, it is not always in the advertiser’s interest to appear overly promotional — indeed there is a danger that people will be suspicious of such use of the advertising media (and we will see examples of this later in the book). The risk is especially high if a campaign is being funded from the public purse, or if the product or policy being promoted might seem to be at odds with the public good. In such circumstances an advertisement will invariably be better received if it gives the impression of merely imparting information.

Figure 1.05 overleaf was part of a 2004 campaign by the British government to encourage pensioners to claim credits that were due to them. In the leaflet form shown here, the casual observer might be reluctant t...