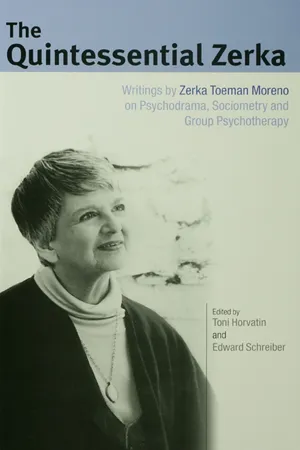

The Quintessential Zerka

Writings by Zerka Toeman Moreno on Psychodrama, Sociometry and Group Psychotherapy

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Quintessential Zerka

Writings by Zerka Toeman Moreno on Psychodrama, Sociometry and Group Psychotherapy

About this book

The Quintessential Zerka documents the origins and development of the theory and practice of psychodrama, sociometry and group psychotherapy through the work and innovation of its co-creator, Zerka Toeman Moreno.

This comprehensive handbook brings together history, philosophy, methodology and application. It shows the pioneering role that Zerka, along with her husband J. L. Moreno, played in the development, not only of the methods of psychodrama and sociometry, but of the entire group psychotherapy movement worldwide. It demonstrates the extent to which Zerka's intuitive and intellectual grasp of the work, combined with her superb ability to organize and synthesize, continue to exert an influence on the field. Toni Horvatin and Edward Schreiber have selected articles that span a career of some sixty years, from Zerka's very first publication to recent, previously unpublished, work. Personal anecdotes and poetry from Zerka herself provide a valuable context for each individual article. The selection includes:

- psychodrama, it's relation to stage, radio and motion pictures

- psychodramatic rules, techniques and adjunctive methods

- beyond aristotle, breuer and freud: Moreno's contribution to the concept of catharsis

- psychodrama, role theory and the concept of the social atom.

This book provides a rich source of insight and inspiration for all those interested in the history, development and practice of psychodrama, sociometry and group psychotherapy, whatever their level of experience. It will be of interest to anyone involved in the fields of psychology, counselling, sociology, social work, education, theatre, or human relations.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Zerka T. Moreno

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Permissions

- Beginnings 1944–1948

- Role Analysis and Audience Structure Toeman, Z. (1944) Sociometry, A Journal of Inter-Personal Relations VII, 2: 205–221

- Psychodramatic Research of Pre-marital Couples Toeman, Z. (1945) Sociometry, A Journal of Inter-Personal Relations VIII, 1: 89

- A Sociodramatic Audience Test Toeman, Z. (1945) Sociometry, A Journal of Inter-Personal Relations VIII, 3–4: 399–409

- Audience Reactions to Therapeutic Films Toeman, Z. (1945) Sociometry, A Journal of Inter-Personal Relations VIII, 3–4: 493–497

- Clinical Psychodrama: Auxiliary Ego, Double, and Mirror Techniques Toeman, Z. (1946) Sociometry: A Journal of Inter-Personal Relations IX, 2–3: 178–183

- Psychodrama: Its Relation to Stage, Radio and Motion Pictures Toeman, Z. (1947) Sociatry, Journal of Group and Intergroup Therapy I, 1: 119–126

- The “Double Situation” in Psychodrama Toeman, Z. (1948) Sociatry, Journal of Group and Intergroup Therapy I, 4: 436–446

- Early Pioneers 1949–1965

- History of the Sociometric Movement in Headlines Toeman, Z. (1949) Sociometry, A Journal of Inter-Personal Relations XII, 1–3: 255–259

- Psychodrama in a Well-Baby Clinic Moreno, Z.T. (1952) Group Psychotherapy, Journal of Sociopsychopathology and Sociatry IV, 1–2:100–106

- Psychodrama in the Crib Moreno, Z.T. (1954) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal VII, 3–4: 291–302

- Note on Spontaneous Learning “in situ” versus Learning the Academic Way Moreno, Z.T. (1958) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XI, 1: 50–51

- The “Reluctant Therapist” and the “Reluctant Audience” Technique in Psychodrama Moreno, Z.T. (1958) Croup Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XI, 4: 278–282

- A Survey of Psychodramatic Techniques Moreno, Z.T. (1959) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XII, 1: 5–14

- Psychodramatic Rules, Techniques, and Adjunctive Methods Moreno, Z.T. (1965) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XVIII, 1–2: 73–86

- The Saga of Sociometry Moreno, Z.T. (1965) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XVIII, 4: 275–276

- Transitions 1966–1974

- Sociogenesis of Individuals and Groups Moreno, Z.T. (1966) In J.L. Moreno (ed.), International Handbook of Group Psychotherapy, New York: Philosophical Library, pp. 231–242

- Evolution and Dynamics of the Group Psychotherapy Movement Moreno, Z.T. (1966) In J.L. Moreno (ed.), International Handbook of Group Psychotherapy, New York: Philosophical Library, pp. 27–35

- The Seminal Mind of J.L. Moreno and His Influence upon the Present Generation Moreno, Z.T. (1967) International Journal of Sociometry and Sociatry, A Quarterly Journal V, 3–4: 145–156

- Psychodrama on Closed and Open Circuit Television Moreno, Z.T. (1968) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XXI, 2–3: 106–109

- Moreneans, The Heretics of Yesterday are the Orthodoxy of Today Moreno, Z.T. (1969) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XXII, 1–2: 1–6

- Practical Aspects of Psychodrama Moreno, Z.T. (1969) Group Psychotherapy, A Quarterly Journal XXII, 3–4: 213–219

- Beyond Aristotle, Breuer and Freud: Moreno's Contribution to the Concept of Catharsis Moreno, Z.T. (1971) Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama, A Quarterly Journal XXIV, 1–2: 34–43

- Note on Psychodrama, Sociometry, Individual Psychotherapy and the Quest for “Unconditional Love” Moreno, Z.T. (1972) Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama, A Quarterly Journal XXV, 4: 155–157

- Psychodrama of Young Mothers Moreno, Z.T. (1974) Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama, A Quarterly Journal XXVII, 1–4: 191–203

- On Her Own 1974–1997

- The Significance of Doubling and Role Reversal for Cosmic Man Moreno Z.T. (1975) Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama, A Quarterly Journal XXVIII: 55–59

- The Function of the Auxiliary Ego in Psychodrama with Special Reference to Psychotic Patients Moreno, Z.T. (1978) Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama and Sociometry XXXI: 163–166

- The Eight Stages of Cosmic Beings in Terms of Capacity and Need to Double and Role Reverse Moreno, Z.T. (1980) Unpublished paper

- Psychodrama Moreno, Z.T. (1983) In H. Kaplan and B. Sadock (eds), Comprehensive Croup Psychotherapy, 2nd edn, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, pp. 158–166

- J.L. Moreno's Concept of Ethical Anger Moreno, Z.T. (1986) Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama and Sociometry XXXVIII, 4: 145–153

- Psychodrama, Role Theory and the Concept of the Social Atom* Moreno, Z.T. (1987) In J. Zeig (ed.), The Evolution of Psychotherapy, New York: Brunner/ Mazel

- Note on Some Forms of Resistance to Psychodrama Moreno, Z.T. (1990) Journal of Group Psychotherapy, Psychodrama and Sociometry LXIII, 1: 43–44

- Time, Space, Reality, and the Family: Psychodrama with a Blended (Reconstituted) Family Moreno, Z.T. (1991) In M. Karp and P. Holmes (eds), Psychodrama: Inspiration and Technique, London: Routledge

- The Many Faces of Drama Moreno, Z.T. (1997) Keynote Presentation to the National Association of Drama Therapists, New York University, New York, November 15,1997

- The New Millenium and Beyond 2000–present

- In the Spirit of Two Thousand Moreno, Z.T. (2000) Plenary Session Address to the American Society of Group Psychotherapy and Psychodrama, New York, March 21, 2000

- The Function of “Tele” in Human Relations* Moreno, Z.T. (2000) In J. Zeig (ed.), The Evolution of Psychotherapy: A Meeting of the Minds, Phoenix, AZ: Erickson Foundation Press

- Suicide Prevention by the Use of Perceptual Sociometric Intervention Moreno, Z.T. (2004) Unpublished paper

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index