1

INTRODUCTION

Harvest time. Out in the wheat fields beyond the village the women and men wield their iron sickles, grasping a handful of stalks with their left hand, pulling the curving blade sharply across them with their right. Behind them more women and the older children gather up the swathes and tie them rapidly with a few twisted lengths of straw, and the sheaves are bundled and strapped onto both sides of a donkey. Almost hidden underneath the family’s livelihood, the little line of donkeys is led down the path towards the village.

Each threshing floor is heaped up with the family’s income for the year. This is not stalks and ears, or an abstract number of kilos or litres. This is bread, porridge, gruel, lumps of cracked wheat and yoghurt dried and stored for making soup in winter. They spread out their harvest across the threshing floor with pitchforks, and bring on the threshing sledge. Two oxen, or a horse and a donkey, or a mule and an ox are hitched to it, and an old man or a couple of children are placed on top of it, sitting on an old wooden chair. There is a constant swish and hiss, like the waves on a shingle beach, as the sledge passes over the harvest and its myriad stone blades cut the grain and straw rolling underneath it.

With a prayer to the appropriate deity or saint – in Cyprus it was the Prophet Elijah – a winnowing wind springs up. With a regular rhythm they shovel the threshed harvest into the air, and let the straw, chaff and grain fall into different fractions across the threshing floor. You hear the crunch of the wooden shovel going into the pile, then a patter and whisper as the grain and straw fall to the ground. Everywhere is the wonderfully rich smell of fresh grain and straw. The grain must now be sieved to clean it further, but the chaff is kept for the chickens and the chopped straw for the family ox. They can now be taken into the family’s courtyard for storage.

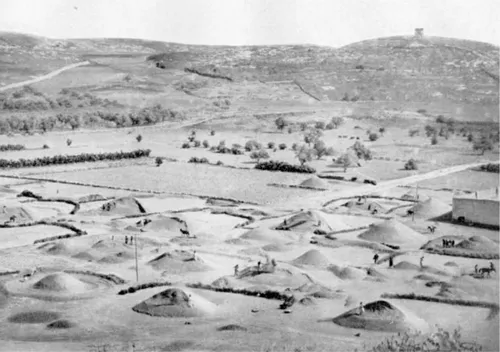

That leaves the pile of grain sitting on the threshing floor (Figure 1.1). This is the very substance of nourishment, prosperity, and the family’s livelihood throughout the year. Pick up a handful, and let the pale kernels dribble through your hand. This is not a symbol of life, or a substitute for money, or a representation of family wealth, pride and prestige. It is that life and wealth, in its ultimate tangible, edible form.

Figure 1.1 Threshing floors heaped with grain outside Nazareth, Palestine, in the early twentieth century. Source: Dalman 1933: plate 12.

And then two strangers come into the village. They come straight to the cluster of threshing floors on the village edge, and begin their work. They are officials; that is immediately clear from the way they dress, and the way they look at the villagers. They might have a uniform or fez or just a badge, as well as smarter clothes and an air of smug self-importance. They go to the first threshing floor, and begin measuring the grain in an old, worn measuring bin. The family and some friends and neighbours stand in a nervous semi-circle, watching every movement as the bin is filled and emptied, filled and emptied. Are they under-filling the bin, these two men, to pretend that there are more measures of grain than there really are? Are they counting the number of bins properly? Will they really take away a third of the harvest as they say, or could the family lose as much as half of its year’s sustenance? What are they like, this year’s tithe collectors? Will they listen to stories of starving children, or perhaps take a bribe in return for a lower count?

The officials finish measuring, and this is the time for negotiation, protest, argument, pleading. But a third or more of the family’s crop is loaded onto government donkeys and taken away to some distant tithe store, never to be seen again. In return, the family receives a piece of paper. The tax men tell them that this paper speaks, and that they must not lose it as it says they have paid their tithes. They look at it uncertainly, and watch the government donkeys carrying away their food.

This is where the experience of being colonized really comes home. It is not so much the pageant of imperialism that affects people’s lives, or the restrictions on speech and political action, or the arrogance of foreign elites. The most direct involvement of ordinary people with imperial rule is when their hard-won food is removed from in front of them and taken right out of their family, their community, and often their country. As well as the loss of livelihood, there is the personal humiliation, the knowledge that they are being cheated, if not by the tithe collector then certainly by the regime.

It makes no difference if the colonizer is a distant imperial power, a foreign landlord who has been given ownership of their village, or a central government supporting its bureaucrats and yes-men by sucking the peasants dry. They are all alien, external, and they all survive by extracting food and labour from their subjects. This is colonialism, as experienced by the great majority of people who lived under it. Tribute begins at the threshing floor.

The archaeology of the colonized

The subject of this book is the experience of colonized peoples, as far as we can reconstruct it from archaeological and other sources. It is not concerned with the rulers or elites who gained by exploiting them. The problem is, of course, that the colonized tend to be ‘invisible’ and ‘voiceless’, only becoming part of history when their rulers decide to write about them. Official statistics and government reports reduce them to numbers in boxes or dots on the map, while foreign travellers filter them through a wide array of assumptions and agendas. Only in a very few cases can their actual voices be heard, transcribed, for example, by courtroom clerks recording their accusations or defences.

What happens if we want to go beyond these elite sources and occasional courtroom records? What if we are dealing with a society where there are no such records? This is where archaeology comes in. People experienced colonial rule in specific situations and actual places, such as the threshing floors of my opening narrative. In many cases these can be visited, described and mapped. Encounters with imperial officials centred round structures and artefacts such as state granaries and measuring bins, which once again can be found and analysed. Even forced labour can leave unintended monuments to the attitudes and experiences of the labourers in the form of the actual structures and public works that they built.

When archaeological material such as this is carefully analysed in a framework based on the theories of postcolonialism and agency, then it does indeed become possible to reconstruct the experience of colonized people, even without historical records. For many periods, of course, the archaeological sources can be combined with historical sources such as taxation records, official documents, historical photographs, ethnography and oral history. When this is possible, it gives a broad array of evidence, with the archaeology compensating for the elite bias of the historical sources.

Colonialism is now a popular subject in archaeology, and has a century-long heritage in studies of ancient Greek colonies and the Roman Empire. This long heritage is in fact one of the problems, as the long-standing focus on elite monuments and art work makes a body of published literature which is very biased towards the rulers rather than the ruled. Farmsteads, illicit whisky stills and labour camps are far more interesting and instructive than palaces, villas and temples, but they are grossly under-represented in the archaeological literature. The increasing popularity of intensive survey and landscape archaeology in the last 20 years has begun to redress the balance, and to focus interest on rural structures and societies. Even so, this study of the archaeology of the colonized must remain to some extent preliminary.

I take a broad view of the term ‘colonized’. In its most restricted sense it refers to people who are controlled and exploited by a group who come from another ‘country’, a term redolent of late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century nationalism. For the colonized themselves, what matters is that they are being ruled by a group they see as being alien: coming from outside, speaking a different language, or belonging to a radically different culture. There is little alienation in giving food as a contribution to your chief ‘s feasting, or in paying taxes to support the local services which you clearly need. It is very different when you are forced to give food, money or your own labour to build a fortress which prevents you from rebelling, or to glorify an imperial metropolis to which you will never go. Clearly there are many different stages and combinations in the long spectrum from identification with your rulers to alienation from them. For the purposes of this book, it has proved more helpful to include a wide range of situations than to exclude those which fall on the wrong side of an arbitrary division.

Words and chapters

The power relations between colonizer and colonized, in all their different degrees and manifestations, are played out in specific situations, whether on the threshing floor, in the government office, or in the labour camp. It is in their actual practice that people dominate, resist, negotiate, compromise. The same applies to archaeologists and academics. We are part of a long tradition of legitimizing colonial rule through providing imperial precedents or stereotyping native character. It is through our own practices that we can reinforce or challenge that heritage. Academic neo-colonialism is not an abstract ideology, but a series of actions and statements that are played out in specific and very real contexts: taking part in a big project abroad; talking to the mixed participants of a conference session; shaping the class dynamics between lecturer and student; reading or writing a book.

In all of this, the words are crucial. Are they alienating and jargon-ridden, intended to display the power and knowledge of the author rather than to achieve any sort of communication? Do they claim to be totally objective and omniscient, and so end up dismissing any alternative voices? Or are they condescending, pointing out the reader’s inferior knowledge and skill? In a book or article, these power relations are played out in the details of the word-smithing.

One small way of trying to create communication and understanding is by narrative. It provides the beginnings of a relationship between a reader and a book, through identification and sympathy, feeling an atmosphere rather than trying to penetrate a logical maze. When the little girl goes exploring in the state granary at Karanis (chapter 6), what she finds is in fact the stuff of site reports and transverse sections. Evoking it through her experience, though, allows readers to lift their eyes from the page and go exploring independently of the author.

Wandering narratives without any structure or theoretical underpinning, of course, are recipes for a confused and frustrated reader, and just produce a different sort of alienation. My theoretical framework is built round four headings: ‘resistance – agency – landscape – narrative’ (chapter 2). Focusing on resistance and agency highlights the active and dynamic role of colonized people in making their own decisions and forming their own communal and social structures, even when that has to be done in the face of colonial oppression. The landscape context is essential for understanding the experience of any group of people, particularly given the importance of dispersed rural activities in resisting colonial rule. Because of narrative’s useful role in the communication of context and experience, its background and function need to be fully explained.

The struggle between the colonized and their rulers over agricultural surplus lies at the heart of the colonial experience. ‘The archaeology of taxation’ (chapter 3) is a new area of archaeological research which investigates this. Archaeological evidence for taxation can be seen in the areas such as threshing floors where crops were processed, in the standard measures that were used, in storage facilities, and in the various seals, stamps and receipts used in the administration of taxation. To demonstrate that this approach can be used even in a prehistoric period, a case study examines the management of the olive oil crop in the valleys of southern Cyprus in the Late Bronze Age.

Colonial rule affects people’s lives in many more ways than just by removing their surplus food. The first thing they had to endure when their area was taken over by a new external regime was ‘the settlement of empire’ (chapter 4). A complex machinery of roads, communications, military forces and administration had to be set up, including of course the facilities for the assessment, collection and processing of taxes. An excellent example of this is the settlement of the Roman provinces of Asia Minor, ancient Anatolia. For people travelling or living ‘on the road’, there were constant duties of forced labour and forced hospitality, as well as regular military posts along the roads themselves. Many people chose to exploit these new situations, and a large and prosperous pro-Roman elite grew up in the cities. Many others chose to stay ‘off the road’, and either lived as bandits or groups in semipermanent rebellion, or else continued with their rural lives with only a minimum of intrusion from the Roman administrators and officials.

The common colonial obsession with census, survey and mapping meant that for many the experience of being colonized was one of ‘living between lines’ (chapter 5). This was particularly the case for Cypriot forest villagers and goatherds under British colonial rule in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To protect the forests, the British forestry department mapped out the boundaries of state forests and marked them with whitewashed masonry cairns. They directed a battery of regulations and exclusions against the Cypriots, who responded with an equally wide range of activities. These ranged from maintaining their detailed knowledge and understanding of the forest landscape to downright disobedience and arson attacks.

For many, the experience of colonial rule was a very physical one, and every blow was felt in ‘the dominated body’ (chapter 6). This was the case even with something as apparently mundane as the processing of the grain tax in Roman Egypt. Farmers and their families had to deliver the grain to the state granary themselves, as well as undergoing a wide range of other unpaid and highly laborious duties. In all the towns, along the roads and along the rivers were a series of gates and barriers which controlled their physical passage from one place to another. For all the impressiveness of monumental architecture, it can also be an unintended monument to the labour of thousands of people, often forced labourers. This can be seen in the contrasting cases of the pyramids of Old Kingdom Egypt and the Nazi building plans for Nuremberg and Berlin. Is participation in such massive projects intended to incorporate people into a new state, or alienate them through punishment?

Resistance to colonial rule is often played out in people’s conversations and stories, and can centre on figures such as the Cypriot Saint Mamas, ‘the patron saint of tax evaders’ (chapter 7). In the Medieval and Ottoman periods his story and the many landmarks associated with him encouraged people in their attempts to grow food for themselves and their families without the knowledge of their rulers. The evidence for this can be seen archaeologically in remote production areas such as threshing floors and pitch kilns, which were clearly operated away from the knowledge of the colonial regime. Sometimes archaeological survey can find whole settlements which seem to have escaped the colonial surveyors and tax assessors.

Social changes in the highlands of Scotland in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries stimulated some very striking examples of ‘landscapes of resistance’ (chapter 8). Before the highland clearances and agricultural improvements, people in the farming townships had an intimate knowledge of their local landscape and the rhythms of rural life which bound together themselves, their settlements, and their environment. Those rhythms were broken when they were expelled to unproductive coastal sites and forced to become labourers, fishermen, or to emigrate outright. In contrast to the picture of depressed and passive acquiescence given by many eyewitness accounts and modern historians, an archaeological study of the landscape shows that there was a wide range of activities that allowed people to maintain their pride and identity and their knowledge of an integrated landscape. One of these was the production of illicit whisky, which became an enormous industry in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

This book includes a wide range of case studies, from Old Kingdom Egypt to post-Medieval Scotland, and from Roman Anatolia to Nazi Germany. They are intended to illustrate an approach which can be applied to many different societies, and to suggest ways of understanding social relationships and experiences at a local level where historical sources are few or unhelpful. The voice of the colonized may be drowned out by elite sources or ignored by generations of archaeologists, but it is always there.