- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1998. This is an accessible book about working with people who have challenging behaviours for professionals, parents and carer. The focus and emphasis is on the practicalities- what is good practice? What do you do in challenging situations? What are good incident management procedures- particularly ones avoiding needless conflict and the user of dominance by staff? How do staff work together, plan and problem solve? Staff from a variety of disciplines provide accounts of their work and the editor's commentary and summary highlights issues of practice, technique and theory from the accounts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Commentary: Helping the Person Learn how to Behave

Introduction

Firstly a confessional, to assist the reader further with understandings about my orientation to the contents and purpose of this book. I started working with people with learning difficulties as a teacher, more than 20 years ago. Circumstances and some of my own preferences caused me quickly to gravitate to working with people who had challenging and, frequently, severely challenging behaviours.

In my early years, I was fortunate to work with some lovely colleagues who taught me many useful things about doing this work. It would also be true to say, however, that attitudes and practices were in general somewhat different in the mid 1970s. My experience was that there was a more easygoing attitude to what staff were allowed to do in order to control people’s behaviour and to try to make the behaviour go away. Shouting, being angry and the use of casual physical force were much more in evidence as part of the staff’s technique. I was one of these staff. Being allowed, or even expected, to indulge in that behaviour style unfortunately chimed in with some existing tendencies in my personality to indulge occasionally in angry and aggressive behaviour.

However, I moved on and changed. Bitter, often painful, experience taught me that it was very difficult to change people and the way people behaved simply by dominating them and demanding that they behave differently. I commenced a happy and as yet incomplete process of addressing the personal factors which contributed to my own occasional challenging behaviour. Significantly I started working with a staff group who increasingly dedicated themselves to cool, technical appraisals of the people and the challenging behaviours they were presented with. They dedicated themselves also to the development of the warmest and most understanding set of practices they could devise. Most of them were younger or less experienced than me, but with them I learnt proper calmness, how to defuse situations, how not to get into situations you didn’t have to be in, and how to be truly relaxed and positive. We were working with people who were likely to provide the more severe challenges and we loved our work. I hope the reader will be comforted, however, by my mentioning that whatever criticisms of ‘poor’ practices might be implied by some of the points in this book, I have probably indulged in those practices.

The following chapters all describe practice which reflects the preferences I have developed for what should be the basis of good work with people’s challenging behaviour. The intention is to describe the experiences of staff who enjoy working with people who are difficult to be with, who feel that they are, at the very least, effective as practitioners, and to give a feel for what it is that they do. The emphasis is on the practical and the basic, and the thought and discussion which goes with those things. This emphasis is much influenced by John Harris’ formulation of ‘everyday good practice’ (Harris and Hewett 1996).

‘Everyday good practice’ implies the necessity for staff to put a great deal of thought and energy into developing positive attitudes and acquiring good interpersonal skills for managing people’ schallenging behaviour effectively. Hand-in-hand with everyday good practice should be attention to needs such as making the environment agreeable, having good programmes of work for matters such as communication and relationships, helping people progress, develop and move forward, as well as teamwork and documentation of their work. If these basics are properly addressed, challenging behaviours can feel less challenging and most people will be less challenging.

Working with people’s difficult feelings and the behaviour generated by them can seem like a complex affair, but it can be reduced to two straightforward aims:

- cope with the way that the person behaves at present;

- help the person to make progress and change.

Coping may be the aim which is frequently not properly attended to for several reasons. Staff can feel under a great deal of pressure to ‘cure’ people of challenging behaviour, and as quickly as possible. This aspiration can lead to inadequate time and energy being spent on developing good coping procedures. Some very human frailties can get in the way also. When a person’s behaviour is particularly challenging, it can be easy to become so fixed on changing the person as a priority, that one forgets to put effort into coping. Additionally, a feeling of resentment that the person just should not be behaving like this, can also be a barrier to giving coping procedures the time and effort they deserve.

Most people do not change their lifestyle and behaviour easily and quickly, so it is good practice to make the priority the ability to cope well with the reality of how they presently behave. Staff groups who do this are then in a much better position to operate the second aim – to do good, effective work with the person on changing and moving forward with their abilities and understandings. The contributors show these two elements as essential strands in their work – a fundamental orientation to viewing their work in as simple and straightforward fashion as possible.

Themes Present in the Work of the Contributors to This Book

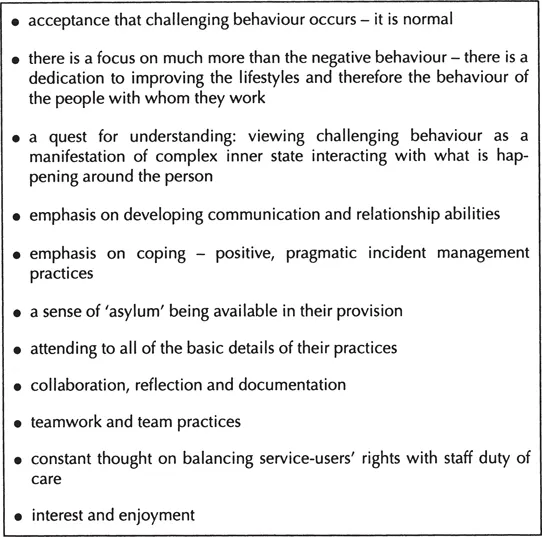

As well as those aims outlined above, other clear themes regularly recur in the stories of practice in this book. The contributors were selected partly because of the diversity of their working situations and the people with whom they work, yet the similarity of so much they describe about their work is a striking feature. Some of the more prominent themes are listed in Figure 1.1. These comprise what may be seen as a ‘practical audit’ of pointers to achieving good practice and each is discussed here in turn.

Figure 1.1 Themes present in the work of the contributors

Acceptance that Challenging Behaviour Occurs – it is Normal

This is the most realistic attitude for staff working with people with learning difficulties to maintain. It can be difficult, especially if staff have ‘curing’ the person quickly as an absolute priority. Tracey Culshaw (Chapter 7) illustrates this. She worked hard with her staff to foster this viewpoint, she wanted it to be a central aspect of staff attitudes and practice. The possession of this attitude contributes to teams and individual members of staff developing practices whose starting point is compassion and understanding. It is one of the foundations of the staff’s ability to remain calm in difficult circumstances and to deal effectively with their own feelings of anger and frustration. It is not in contradiction of the next item below; effective staff maintain both of these viewpoints simultaneously.

There is a Focus on Much More than the Negative Behaviour – There is a Dedication to Improving the Lifestyles, and Therefore the Behaviour, of the People With Whom They Work

The writers here all show the lack of surprise, indignation or resentment at the styles of behaviour they are presented with, which is implicit in the acceptance stressed above. This acceptance does not impede their desire or drive to help each person to find more profitable and rewarding ways of interacting with the people around them. They are able to have an approach which does much more than negatively focus on eradicating the challenging behaviour. They pay attention to many aspects of the person’s lifestyle, attempting to enrich it and diversify it, particularly in respect of social understandings and social interaction. There is a fundamental belief that doing this is more effective than simply focusing on eradicating the unwanted behaviour.

A Quest for Understanding: Viewing Challenging Behaviour as a Manifestation of Complex Inner State Interacting with what is Happening Around the Person.

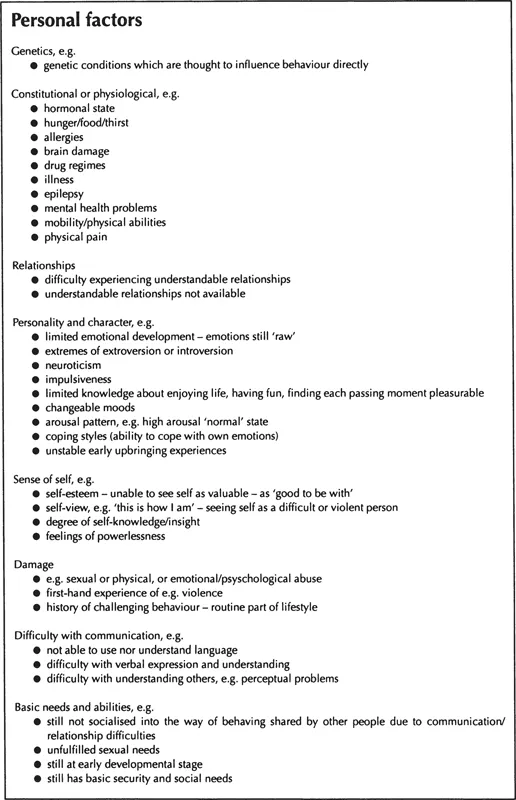

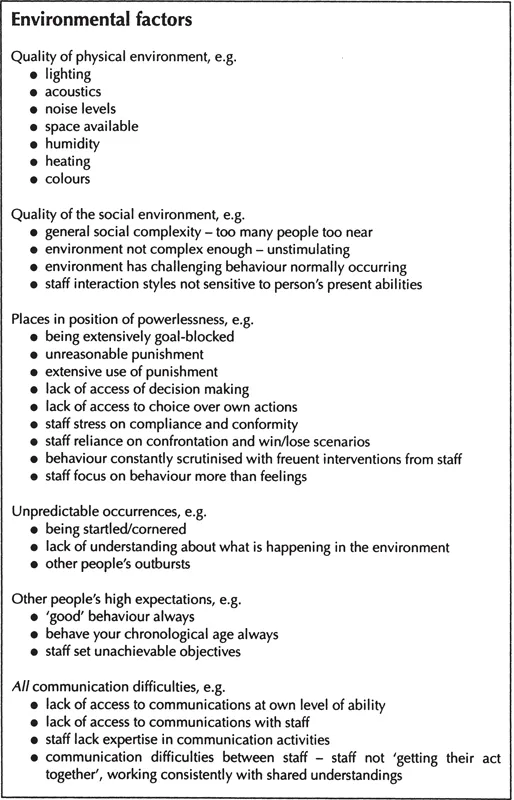

All contributors describe their thoughts on what contributes to the behaviour of the person they are working with. None of them view it as a straightforward issue – there is no great search for the single ‘cause’ of the person’s behaviour and a correspondingly ‘quick fix’. They are all sensitive to the ‘triggers’ of challenging incidents, and there are good examples of approaches to dealing with triggers – by removing them where possible, managing the effects of them where it is not. However, they do not confuse the trigger with the cause of the person’s behaviour. The practitioners writing here recognise the degree to which various factors come together to ‘cause’ the way that a person behaves and to create possible triggers. Nicki Bond and Don O’Connor (Chapter 3) offer a stark list of some of the factors they judge to be present in Andrew’s behaviour. Helping the person to move forward and develop more positive interactions with the world may sometimes be a seemingly complex and painstaking affair of working on the contributory factors inside the person and paying attention to and changing wherever possible, the contributing factors outside the person.

This approach to viewing the causes of the person’s behaviour is illustrated in Figure 1.2 and 1.3. The lists are not exhaustive, but they outline some of the more usual factors which are likely to contribute to the challenging behaviour of people with learning difficulties in our services. (Actually, the lists are useful for all of us in thinking about our own occasional challenging behaviours.) They give a framework for thinking about the aim of helping the person with challenging behaviour to progress and change. They should assist with the development of the sort of work that the contributors carried out on starting to get the world right, working on communication, relationship and well-being, the elements of the environment which interact with personal factors. Simply sitting together and using the lists to do a brain-storm with a service-user as the subject, can be a significant experience for staff teams. The written results can bring home the reality that a great many serious influences are contributing to the behaviour of the person and that it is understandable that she/he indulges in some behaviours which are difficult to deal with.

Figure 1.2 Common personal factors underlying the production of challenging behaviour

Figure 1.3 Common environmental factors underlying the production of challnging behaviour

This conceptualisation underpins the approaches in the various chapters. The contributors are not seeking simply to make the behaviour go away and view that as the job done. They consider the likely factors affecting their service-users, put in place a range of initiatives which address these factors and work to have an environment which is as agreeable as possible. There is even the perception that the people writing here would not be content in their work if the challenging behaviours stopped, but the person with learning difficulties was still unhappy, distressed or isolated.

There is great concern for how people with challenging behaviour view themselves – the issues of self-esteem and self-view. Work on communication and relationship goes hand-in-hand with these issues and is likely to contribute mightily to a person’s self-worth if she/he is having regular positive valuing experiences in interactions with others. This is an area which might require great thought and professionalism, however. It can be very difficult indeed to give, or even desire to give, positive human experiences to a person who is difficult to be with and generally displays negative or abusive behaviour towards others. There is no doubt that these positive experiences are necessary and likely to increase people’s sense of feeling good about themselves, resulting in positive effects in their behaviour. It is only recently that discussion of issues of self-esteem have become more prominent in work with people with learning difficulties (see also Clements 1997, Stenfort Kroese 1997). Whilst the discussion here is short, I would hope that the reader none the less recognises its status as a major issue in the work of the contributors.

While working with a concept of factors may seem to be a complex undertaking, there is none the less also a strong sense that the staff writing here view it as a logical and highly practical way of working. They are also flexible, reviewing their conceptualisations of their service-user’s state and modifying their action plans accordingly. No procedures become ‘carved in stone’, staff complacency can turn out to be a significant environmental factor in challenging behaviour occurring.

Emphasis on Developing Communication and Relationship Abilities

There is striking repetition of these issues in the accounts. Rosemary Hawkins’ work (Chapter 11) with Ann is fully focused on these factors, in recognition that her behaviour is part of a lifestyle formed by her limited abilities to make contact with other people. Although Ann was ‘full of life’, little of it was concerned with relating to others. One of the major contributing forces to a person learning to have ordered behaviour is the effect and influence of other people’s behaviour on them. If the person has limited ability to relate and communicate with others, she/he has correspondingly limited opportunity to be socialised into the ways of behaving shared by others. This recognition of a person’s ability should have a fundamental effect, as it did for Rosemary Hawkins, on the extent to which people with very severe learning difficulties are expected to have self-control and be ‘disciplined’ by external forces. Realistically, they may have little ability to respond in this way. This does not mean that staff should not be doing what they can to control the person, but it does mean that such attempts to control should take into account the person’s actual ability to have self-control and be set also within a more far-ranging application of effort on communication and relating.

Although Ann presents us with the most extreme example of this state of affairs, the issue applies equally to the work of contributors who may be caring for or teaching people with more developed abilities. They all recognise the absolutely fundamental nature of communication in human behaviour and that lack of social understanding results in so much difficulty. Karin Purvis (Chapter 7) illustrates this application even with people who have apparently extensive ability to speak and understand speech. In my work with the staff group I described earlier, we powerfully formed the view that even small improvements in communication ability could have correspondingly beneficial and welcome outcomes in terms of behaviour (see Nind and Hewett 1994). The message from the contributors here is simply, never have a behaviour programme – without also having a communication programme.

An Emphasis on Coping – Positive, Pragmatic Incident Management Practices

Coping first and foremost is a major theme of the accounts. Coping well with the person’s behaviour and all aspects of the working situation is attended to in detail. Some of the writers, notably Maggie Roberts (Chapter 8) and Nicki Bond and Don O’Conner (Chapter 3) may be considered fortunate to have working situations where appropriate time could be devoted to these considerations, without the compromises necessitated by the conflicting needs of more than one student or client. However, the work of Bernard Emblem’s (Chapter 4) staff also illustrates the team pragmatically adjusting themselves to the reality of the behaviours they were presented with. This was partly influenced by whether the person actually has the ability to be ‘controlled’, but also by some seemingly natural serenity on the part of the staff. The result was some realistic and practical approaches to incidents, coping well with what takes place, while working hard at all other times to help the person progress.

There is also the reality that coping can take time. Lewis Janes and his staff (Chapter 10) worked through some long situations with Brenda. Their ‘patience’ was partly founded on a realistic appraisal of the consequences if they did not give the time necessary, and partly on an implic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Commentary: Helping the Person Learn how to Behave

- 2. Positive Incident Management – Insights from Staff Involved and Issues for the Organisation

- 3. A Flat for One – Social Service Provision at the Extreme

- 4. The Challenge of Class Six

- 5. Commentary: Managing Incidents of Challenging Behaviour – Principles

- 6. Working with People with Challenging Behaviour in a Further Education Class within a Long-Stay Hospital

- 7. Developing Practice in a Residential Team – Training, Talking, Thinking, Working

- 8. Andrew – A Classroom for One

- 9. Commentary: Managing Incidents of Challenging Behaviour – Practices

- 10. Leading a Well-Challenged Social Services Residential Team

- 11. Ann – the Challenge of a Difficult to Reach Five Year Old

- 12. Exotic Communication, Conversations and Scripts – or Tales of the Pained, the Unheard and the Unloved

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Challenging Behaviour by Dave Hewett,David Dalby in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.