![]()

1

THE GREAT VARIETY OF SPORT BRANDS

The sport marketing literature and the sport brand literature in particular provide various brand classifications. According to a classical perspective, authors either position their classification from the creation and production side (offer) or from the behaviours and contexts of consumption side (demand). As an example, in France, Megabrand System is a brand classification elaborated by the firm Taylor Nelson Sofres which identified nine categories of brands across all markets:

• star brands;

• champion brands;

• everyday-friend brands;

• alternative brands;

• landmark brands;

• baron brands;

• contested brands;

• unknown brands; and

• brands with potential.

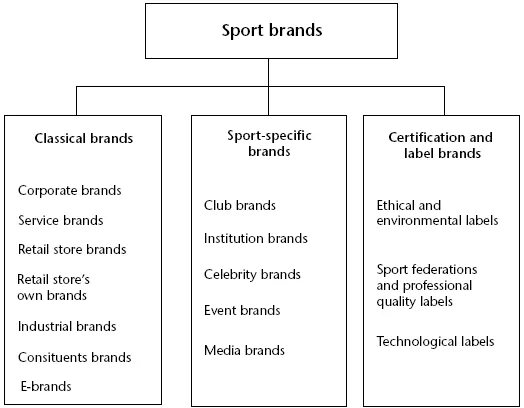

If all classifications provide a different perspective, their profusion creates confusion and does not give credibility to the ‘brand science’. In 2004 Lewi warned that the number of categories of brands and sub-classifications should remain limited in order to keep it clear and simple for managers and consumers. Indeed, according to the contexts and the theoretical fields of analysis, new categories and terms are used such as ‘umbrella brands’, ‘generic brands’, ‘own brands’, ‘parent brands’, ‘source brands’, or ‘guarantee brands’ which generally only add tiny nuances, in comparison with the categories traditionally and widely used by practitioners and experts. They certainly are indicators of an increasing interest and focus on brands but they also tend to blur the identification of brands’ roles and functions either from an economic, cultural or social perspective. Therefore, in order to clarify the roles and functions of sport brands it is necessary to identify their main categories. Besides the types of brands usually found in all industries (corporate brands, service brands, constituent brands and e-brands) that we call ‘classical brands’, two other distinct categories can be identified in relation to sport brands (see Figure 1.1): sport-specific brands and certification and label brands.

FIGURE 1.1 The three main categories of sport brands

Classical brands

Classical brands have been widely considered and analysed in management and marketing textbooks and comprise corporate brands, service brands, and store and distributor brands. Within this category, industrial brands require a specific treatment because, as suppliers’ brands, they can be found and associated with many other brands. Finally, e-brands are also analysed separately.

Corporate brands and trademarks

Historically, the name of a company has constituted the main recognition sign for a brand, and then identifies the corporate brand. Often associated with the manufacture, the founder or the place where a product is made, corporate brands constitute the model for most major contemporary brands. Also frequently linked to a familial enterprise or tradition, they create, manufacture and sell their products which are clearly identified. The development of the service economy however, significantly modified this pattern. Brands in this category are often leaders of their market and are very frequently megabrands with international awareness and reputation. Corporate brands often aim to keep a tradition or a ‘home spirit’, often characterised as their DNA, which relies on respect for specific values and the protection of a unique expertise or know-how. With these brands, the brand’s history very often overlaps the company’s history. For many of them, the name of the brand is the name of the company which is also the name of the founder and entrepreneur. All products are then generally branded under the same appellation. In the sport industry, huge corporate brands such as Nike, Salomon, Adidas, Shimano, Wilson or Prince represent classical examples but sport corporate brands of this dimension are, actually, not so common. Dorotennis, a women tennis clothing specialist is another typical example. After being a pioneer in the 70s, this brand has become a leader in women’s sportswear and is nowadays managed by the founder’s daughter. In another sector, the sport boat industry, Zodiac is a good example of a corporate brand with all its products branded with the company name.

However, besides these well-known and high-profile corporate brands, the hyper-segmentation of the sport markets has allowed the emergence of new corporate brands, either new in their structure or in their philosophy: subculture brands and lovemarks. They generally represent very small companies which have a niche positioning and whose products are limited and sometimes crafted or handmade. Their appeal and reputation mainly rely on the valorisation of a name, an innovation and an alternative and avant-garde image which also represents the key characteristics of their business model. They are above all brands of passionate people for passionate people which mean that they are often associated with emergent and new sport practices such as the sliding ones (e.g. surfing, snowboarding, skating or kite-surfing) illustrated by Quester, Beverland and Farrelly (2006). The most recent examples of brands from the skiing sector such as Movement and Bumtribe do not directly compete with the major ones and target people interested in new, technical and original offers in line with free-ride and free-style practices. Proof of their efficiency and model: many of the subculture brands’ ideas and concepts are copied by the major dominant brands of the sector.

Easy to identify, store brands rely on the reputation of distribution chains and companies. Like corporate brands, they were born in the industrial era but really took off with the advent of the consumer society and the mass distribution of corporate brands’ products. Intersport, Decathlon (property of Oxylane Group), Sports Direct International plc, JD Sports Fashion plc (JD), and Foot Locker are all examples of sport specialised retail brands. However, store brands should be distinguished from stores’ own brands and not all stores or chain stores distribute their own products. In many aspects, stores’ own brands can appear like corporate brands: they are owned by retail stores but their name is different. Sometimes names are even different between the types of products. This is for example the case in Europe with Decathlon and its own sport brands such as Tribord (for nautical sports), Artengo (for racket sports) and Quechua (for outdoor activities). These brands’ products can only be found in the owner’s stores. These store’s own brands are often created to respond to the demand of chain and retail stores that want to increase their profit margins and/or cannot obtain exclusive products and deals from corporate brands to differentiate them from their main competitors. However, it is not necessary for them to have a visible brand logo or identification as they are sure to be distributed and the stores themselves can guarantee a good shelf position (Malaval and Bénaroya, 1998). This is not the case for corporate brands which need to be clearly identified and distinguished to be distributed in retail stores.

Derived from corporate brands, service brands provide services for both consumers and other businesses. They develop a competence, specific values and a distinct positioning: renting, consultancy, catering, hospitality… In the sport industry, service brands seem to have a bright future due to the increasing craze for sport in general and sport participation in particular. Brands of sport and recreation parks, fitness clubs, sport travel agencies, media, and marketing and communication companies are good examples of service brands. The Intersport international network seems to be a good example. For many years, it has been demonstrating the service values it has been bringing to sport participants by offering for instance online skiing equipment hire. Since 2005 the website of the brand (www.intersportrent.com) has had a turnover multiplied by two or three per year. Within the same sector, ski resorts are also service brands because they provide various kinds of sport and non-sport services to visitors, sport participants and tourists.

Industrial and constituent brands

Industrial brands are sometimes named supplier brands. Their main difference from corporate, service and store brands is that they are not well-known by the general public because they are mainly present within business to business markets (B to B). They generally supply manufacturing brands providing different components (for example fabrics and textiles, pieces, material) which are used in the composition of sport goods and equipment, ticketing, club brands’ accessories and merchandised products. Industrial brands allow the final brands to provide offers, thanks to techniques, know-how or skills that the final brands do not possess. For instance a tennis racquet brand needs an industrial production process (machines, transport equipment), information and technological systems (computer-aided design, stock and order management system), maintenance and logistic supports, without which it cannot achieve its objectives. Before becoming in 1994 a brand specialised in the production of tennis racquets (currently ranked 2 worldwide) and sport shoes, Babolat, since 1875, had been a supplier of strings for the main international racquet brands.

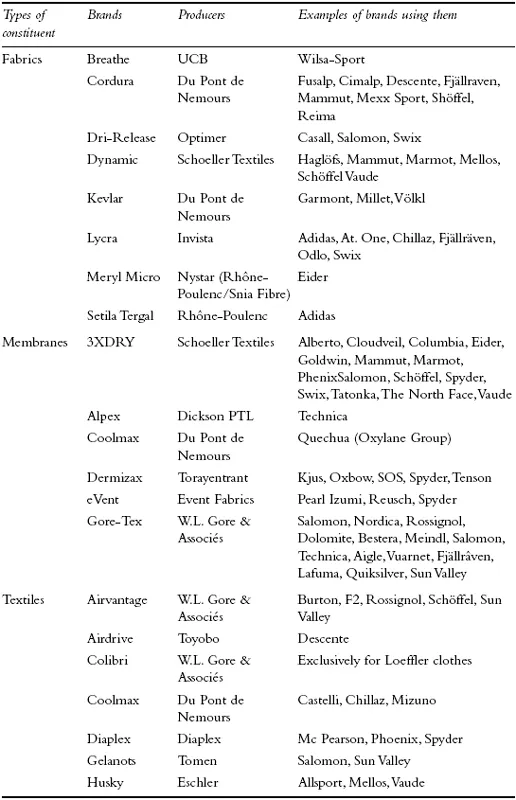

But as we said before, because industrial brands are not always in direct contact with final consumers they are generally not well-known. According to some observers, these industrial brands are corporate brands which did not go to the end of their logic as they stayed at a technological level and did not reach the consumer-product encounter level. The success of industrial brands is linked to the prescription (positive word-of-mouth) surrounding the brands and companies they supply to. In this sense, the success criterion is quite similar to those of B to C brands. Within industrial brands we can distinguish raw and transformed material brands, constituent brands, small equipment brands, big equipment brands, industrial service brands (catering and ticketing functions) and management and consulting brands. With regard to the specificities of sport markets, the focus will mainly concern constituent brands. Contrary to raw material or industrial service brands, some of these constituent brands are well known to the public because their contribution is widely promoted by corporate brands. For instance, in the sportswear sector, Gore-Tex is a constituent brand with a good reputation and a high level of awareness. Sportswear brands extensively use Gore-Tex’s reputation to sell their products because it provides an added value, which is often translated into higher prices too. In the sport goods industry and beyond the brands supplying accessories and specific equipment (for example Shimano and Sach for bikes, Wichard for marine hardware and sailing equipment, Vibram for free climbing rubber compound), are numerous. Among the most famous we can cite Gore-Tex, a brand which belongs to W.L. Gore & Associates, Kevlar, Nylon, and Lycra which belongs to the American giant Du Pont de Nemours. Many others exist but often known only by professionals and specialists (see Table 1.1 for some examples).

These ‘hidden brands’ as Lewi (2004) called them, can become true technological labels whose quality and reputation can even go beyond the final brands that use these constituents. This is for instance the case with Gore-Tex and other Gore products which allow famous brands such as Patagonia, Columbia, Millet, Rossignol, Nike, Lafuma, Rip Curl, Quiksilver, Eider or less well-known brands such as Mammut, ACG, Schoeffel, Trango, Wild Roses, Lowe Alpine to increase their sales of outdoor equipment. In some cases, sportswear brands do not even need to promote their products because of the reputation and image the constituent brand holds. For this reason, sportswear brands increasingly use famous constituent brands because they provide a clear technical and marketing value (see Table 1.2 for an example of constituent brands and final sport brands using them).

From a strategic point of view, this association can be assimilated to a successful functional co-branding and a co-advertising strategy as consumers have become more and more sensitive to constituent brands and because they simultaneously ensure additional revenues and differentiate products (Cegarra and Michel, 2003).

E-brands

E-brands represent a quite new category of brands which are present on the Internet via a website using the name of the brand. Like Amazon, Google or Yahoo, websites which support these brands have become powerful assets. For Lai (2005), e-brands provide three types of services: (1) transactional services, selling online products or services; (2) informational services and (3) relational services, by allowing a brand community to gather, discuss and share their opinions about the brand. The transactional e-brands essentially serve functional and utilitarian purposes; it has to be easy, efficient, clear and comfortable for the consumer. On the contrary, informational and relational e-brands rather serve a hedonist and experiential dimension of consumption (Holbrook and Hirschman, 1982). These e-brands offer many services traditional brands find difficult, such as providing information without time constraints or providing individualised and customised products. Sport markets have witnessed increasing numbers of online transactions and products sold which undeniably demonstrate the consumer appetite for this type of distribution. This is illustrated for instance by a 2012 Mintel report dealing with the UK sport goods retailing market1 which found that two-fifths of sport goods buyers were happy to buy from an Internet retailer. In parallel with these forms of retail, new e-commerce actors such as websites organising private, discount and destocking sales (secretsales.com and vente-privee.com) have also emerged and are showing great success. For instance, vente-privee.com, which boasts to be the global leader in online private sales relying on 14 million members and featuring more than 1,450 major international brands, is present in eight European countries and has just launched a joint venture with American Express in the USA.2 Consequently, several sport-specific websites following the same models have been emerging such as leftlanesports.com, theclymb.com and privatesportshop.com and are now competing with the generalist private sales websites.

TABLE 1.1 Examples of constituent brands in the sport textile sector

TABLE 1.2 Constituent brands and sport brands using them

The progression of e-commerce has forced traditional brands to invest in this new sector. This is the case of retailers which have expanded their offer online such as Sports Direct with sportsdirect.com and Made In Sport with madein-sports.com. Among them, professional clubs and franchises benefiting from a strong reputation have developed their own websites not only to promote their brand but also to sell tickets and products to a wider audience. In this sense, websites allow sport organi...