- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past

About this book

Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past turns what is usually seen as a method for investigating the distant past onto the present. In doing so, it reveals fresh ways of looking both at ourselves and modern society as well as the discipline of archaeology.

This volume represents the most recent research in this area and examines a variety of contexts including:

* Art Deco

* landfills

* miner strikes

* college fraternities

* an abandoned council house.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past by Victor Buchli,Gavin Lucas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Production and consumption

Chapter 2

Models of production and consumption

Victor Buchli and Gavin Lucas

Production and consumption arguably form the central poles of contemporary material life, indeed the material basis of social existence in capitalist and socialist industrialised societies. Much of modern social theory can be caught in the extremes of Marx’s definition of production as the objectification of labour and Baudrillard’s inversion of this formula in an anti-utilitarian conception of consumption. Marx argued that because value in human life came through productive labour, under capitalism neither labourer or capitalist are ultimately content – the labourer because they are alienated from the fruits of that labour, the capitalist because they enjoy what they did not produce. This model, after Hegel’s master and slave relationship, may be over-simplistic, but more importantly it focuses everything around the pole of production which serves as the basis of social and historical existence. The flipside to this perspective, which has tended to dominate the way we see modern society until recently (see the recent works of Miller 1986, 1995, 1998) whether from a Marxist viewpoint or not, is that consumption is unproblematic. Consumption as merely the acquisition of goods on the basis of their utility value – i.e. the provision of basic human needs, and the consumer as the ‘rational man’, making ‘rational’ decisions on the basis of these given needs.

Despite various forays into issues of consumption throughout this century from writers such as Veblen, Simmel and Weber, the study of consumption as a problematic field emerged only in the 1970s and 1980s. Perhaps the earliest critic of consumption was Georges Bataille, who was heavily influenced by earlier anthropological work (e.g. Mauss). Bataille attacked the whole orthodoxy of political economy in his major work The Accursed Share, by challenging the notion that economies worked on a basis of finite or limited resources. Rather he saw this as a restricted conception of the economy and argued that in a more general view, there was always an excess of resources – social and historical structures are not defined on the basis of scarcity therefore, but excess. Cultural life is ultimately characterised by how societies deal with this problem of excess. The notion that consumption, as a means of dealing with excess rather than defined by utility and need was taken up by Baudrillard who has pushed the idea to its limit, questioning both the ‘natural’ basis of human needs and the ‘natural’ uses of objects – needs are not given but socially and culturally created, objects are not inherently useful for anything but can indeed become whatever we want them to be.

In terms of mainstream cultural studies of the 1970s and 1980s, two different strands are identifiable. One, coming out of the same post-modern context as Bataille and Baudrillard, has focused on consumption as a symbolic and semiotic rather than strictly utilitarian activity – the works of Baudrillard but also Barthes exemplifying this strand (Barthes 1973; 1977; Baudrillard 1981; 1996). The other falls more within an empirical and sociological framework and has studied the way consumption is not merely a passive but a creative activity which different groups within society use as a means of self-expression – works by Hebdige (1993) and others on sub-cultures and Bourdieu on class (Bourdieu 1984). Today, both these strands feed into a dynamic and increasingly significant area of research which cross-cuts disciplinary boundaries (Miller 1995; 1998). Indeed, Miller has made a key point about consumption, which in a way takes us back to Marx and the emphasis on production; Miller argues that in contemporary society, precisely because we are alienated from production (most of us do not produce what we consume), consumption, not production, has become the prime means of forging a relationship with the world (Miller 1995: 17). It is moreover within consumption and not production that some of the major social contradictions confront us, epitomised in the figure of the housewife. This has been especially apparent in feminist works. Miller argues that the housewife can metaphorically stand in for the contradictions of the modern consumer, being both of low social status and yet at the same time wielding huge power through choice in a global market economy, ‘the consumer as global dictator’.

Despite the shift though towards consumption as a key category of analysis in modern material culture studies, is there a sense in which the relation between production and consumption has not been properly deconstructed? There is no doubt that there is a disjunction between producers and consumers in terms of both class and geography – but this has probably always been a component of life, even in pre-industrial societies. There is a lurking myth behind the Marxist critique of alienation, the myth of the pre-industrial lifestyle as one of near self-sufficiency so that people lived directly off the products of their own labour. This of course ignores the processes of specialisation and exchange that occur and have occurred in most pre-industrial societies (Sahlins 1974). More generally, the notion of producing in order to give away, in order not to enjoy the product of one’s own labour, is a theme resonant in sacrifice and gift-exchange; Bataille’s point is in fact that people have always been defining themselves more through such acts than everyday production for one’s own consumption. The converse is also the case – we do not just consume for ourselves but also for others – and here Danny Miller’s recent work on shopping and sacrifice, drawing explicitly on Bataille, is a good example (Bataille 1991 and Miller 1998).

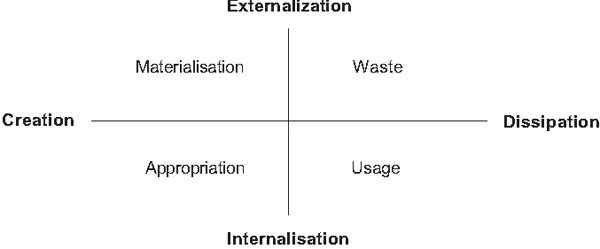

Perhaps we should compare this basically Marxist model of the relation between humans and artefacts with the conventional archaeological model. The Marxist model, constructed from the human viewpoint, articulates the relation in terms of objectification/externalisation and appropriation/internalisation – a kind of cyclical model whereby the production and consumption of material culture is articulated through the externalisation of ideas into things, and then re-internalised into ideas again. In contrast, the archaeological model is more from the viewpoint of the object and expresses the same relation in terms of culturation/c-transforms and naturalisation/n-transforms whereby the production and consumption of material culture is articulated through the synthesis and construction of raw materials into artefacts and their subsequent breaking down and decay back into the natural system. Conjoining the two models in a single diagram, we obtain that shown in Figure 2.1..

The diagram shows two axes, one marking the processes of externalisation and internalisation, the other, those of creation and dissipation, together making up a grid of production and consumption. In each of the four cells delimited by this grid is a term that sustains both the social and physical models of the production– consumption cycle. Starting clockwise in the top left-hand side, the concept of materialisation articulates the process of creative externalisation – that which incorporates both the idea of objectification and production/ manufacture. Moving on, dissipative externalisation is characterised by the term ‘waste’, in the sense of both ejecta and decay, that which is thrown out (of the body, of the house, of society) and which decomposes, breaks down. Dissipative internalisation can be understood through a dual definition of usage, as both ‘using up’ and ‘using for’, to consume an object so it is taken out of circulation or the economy, and to consume it for some purpose. Finally, creative internalisation is appropriation, the attachment of an object to the self or group so it becomes part of its identity and at the same time transforms or shapes that identity.

The chapters that follow can all be seen to investigate different aspects of this grid. All three share in common a commitment to the role of archaeology in investigating these aspects, indeed argue that it can provide something that most other disciplines lack – a strong and long tradition of dealing with material culture. More particularly, Majewski and Schiffer’s and Stevenson’s chapters primarily deal with the creative, left-hand side of the grid, with the issues of materialisation and appropriation. For example, in distinguishing the processes of invention, commercialisation and adoption, Majewski and Schiffer provide a framework for understanding how commodities are materialised, both as part of social and technological processes. Furthermore, in arguing for consumerism as a key term, as something that goes beyond consumption, they are stressing the importance of active consumption or appropriation, the fact that the consumption of goods can be used creatively to alter identities, the economy and more generally the material world, as in the case of the ‘Japan Craze’ in the late nineteenth century. Similarly, Stevenson argues for the active nature of consumption and in the context of design and art history, critiques generic terms such as Art Deco as masking the everyday processes of materialisation and appropriation within which most everyday objects such as ceramics are implicated.

Figure 2.1 Production and consumption.

Significantly, there are a number of similarities in these two chapters – for example, as well as both using case studies of ceramics, both raise the issue of the distinction between high/fashionable style and traditional style as being an important dynamic. Stevenson’s paper in particular brings this out most forcefully in discussing the contradictions in Clarice Cliff’s ‘Art Deco’ ceramics, which were ‘domesticated’ translations of high Modernism as expressed by leading artists of the period. Not only do her ceramics exhibit this duality in design or materialisation through the conflation of Modernist forms with traditional decoration, but also in their consumption or appropriation whereby these modern ceramics were often placed in very traditional, non-modern settings of the contemporary home. The tension between the ‘high’ and ‘traditional’ is thus one good example of how to understand the creative processes of production and consumption.

It seems fitting to start off the book with archaeological case studies of ceramics. They are more traditionally recognisable as archaeological and provide an opening through which we can approach archaeological studies on more recent subjects and their particular emphasis on consumption. It also provides a self-reflexive approach to archaeology’s methodological beginnings as well as earlier forms of modern consumption, for the rise of consumerism and material culture studies along with ethnology and archaeology occur together in the second half of the nineteenth century (Löfgren 1997: 111). Additionally, the role of pottery as the archetypal, traditional waste debris of archaeological contexts is an appropriate way into the aesthetics of waste that Lupton and Miller argue characterises the experience of Modernism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Lupton and Miller 1992). Such quotidian waste has traditionally been the empirical basis of archaeology.

Rathje’s chapter thus takes us to the other side of the grid, to dissipation, both as consumption and waste. While his main point is to emphasise the importance of an integrated archaeology, the strength of Rathje’s garbology can be said to lie in its investigation into the dissipative nature of contemporary society. Through identifying major discrepancies between reported and actual behaviour, the relation between waste and consumption has been painstakingly studied through investigations of fresh and landfill garbage over three decades and produced a wealth of information, his ‘First Principle of Waste’ being a good example. The less consumption behaviour varies, the less waste is generated; such a principle can be seen as a different perspective on the tension between traditional and popular styles elaborated by Schiffer, Majewski and Stevenson. Insofar as the dynamic of old-fashioned and in-fashion articulates processes of materialisation and appropriation, the very speed and variability of this dynamic can be said to articulate processes of usage and waste.

To summarise, the overall social effects of the archaeological act – whereby absence is presenced – can be seen here in terms of the critical insights that Majewski and Schiffer and Stevenson bring to the genealogies of consumer practices and product design that are too often concealed in dominant cryptohistories (Schiffer 1991). Similarly, Rathje’s work offers a more direct critical intervention into our understanding of consumer practices, literally examining the consequences of our excesses – critically presencing what has been dissipated, buried and wasted in order to support our dominant myths buttressing modern consumerist societies.

References

Barthes, Roland (1973) Mythologies, London: Paladin.

Barthes, R. (1977) Image, Music, Text, Glasgow: Fontana/Collins.

Bataille, George (1991) The Accursed Share vol.1, New York: Zone Books.

Baudrillard, Jean (1981) For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign, St Louis: Telos Press.

Baudrillard, J. (1996) The System of Objects, London: Verso.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1984) Distinction, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Hebdige, Dick (1993) Subculture: The Meaning of Style, London: Routledge.

Löfgren, Orvar (1997) ‘Scenes from a troubled marriage’, Journal of Material Culture, 2(1):

95–113.

95–113.

Lupton, Ellen and Miller (1992) The Bathroom and the Kitchen and the Aesthetics of Waste, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Visual Arts Center.

Miller, Daniel (1986) Material Culture and Mass Consumption, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Miller, D. (1995) ‘Consumption as the vanguard of history’ in D. Miller (ed.) Acknowledging Consumption, London: Routledge.

Miller, D. (1998) A Theory of Shopping, Cambridge: Polity.

Sahlins, Marshal (1974) Stone Age Economics, London: Tavistock.

Schiffer, Michael (1991) The Portable Radio in American Life, Tucson and London: The University of Arizona Press.

Chapter 3

Beyond consumption Toward an archaeology of consumerism

Teresita Majewski and Michael Brian Schiffer

In 1982, Kent V. Flannery ridiculed archaeologists – garbologists in particular – who had taken up the analysis of modern American artifacts. Despite Flannery’s denunciation, Rathje’s ‘Projet du Garbage’ and other modern material culture studies have survived and prospered. As a genre of archaeology, however, modern material culture studies have low visibility because, we suggest, they lack a thematic focus. In this paper, we attempt to remedy this situation by redefining modern material culture studies as the archaeology of consumerism, following scholars such as Martin (1993), Schiffer (1991), and Spencer-Wood (1987a).

Modern material culture studies are usually taken to be research on the artifacts of industrial societies that can furnish information about those societies (e.g., Gould and Schiffer 1981; Rathje 1979; Rathje and Schiffer 1982). But, in light of current research in ethno-archaeology and historical archaeology, this definition seems too limiting. For example, in the ethno-archaeology of traditional communities, many investigators, including Lewis Binford (1976), Susan Kent (1984), James Skibo (1994), and Brian Hayden (1987; Hayden and Cannon 1984), have recorded and analyzed imported artifacts of industrial manufacture. These projects suggest that ethno-archaeology in traditional societies, and modern material culture studies ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Production and consumption

- Part II Remembering And Forgetting

- Part III Disappearance and disclosure

- Conclusions