1

NUBIA, THE SUDAN AND SUDANIC AFRICA

Introduction

The name of ‘Nubia’ has long been used to describe Egypt’s southern neighbour. Various forms of the name are known, in many languages, since it first appears in classical sources. In the medieval period – known mainly through Arabic sources – Nubia was a large and often ill-defined region covering much of the modern Middle Nile Basin. More recently it has had a more restricted meaning, limited to riverine areas of northern Sudan and southern Egypt, where Nubian languages were still spoken. Historically, other names have also been applied to this region and its inhabitants, ‘Kush’ being a widely used term in the Ancient World, as well as ‘Aithiopia’. To the Arabs, this was all part of a larger ‘al-Bilad as-Sudan’.

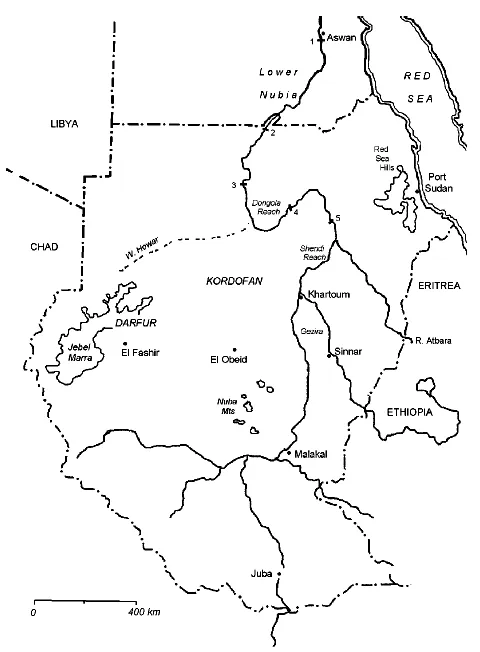

Looking beyond Nubia, however defined, this book will also explore the wider archaeology of the modern Republic of Sudan, which includes the Middle Nile Basin and much of the Upper Nile (Figure 1.1). In its present form the Sudan is, to a large degree, a product of historical processes of the nineteenth century, if rooted in earlier periods. From the 1820s, the Funj Sultanate of Sinnar, heirs to a long history of riverine states, was incorporated into the domains of an expanding Egyptian state. Egyptian ambitions were to extend far beyond the river valley, developing long-standing Ottoman interests along the Red Sea littoral and also looking to the savannahs of the west. Moving first into Kordofan and then Darfur, as well as pushing south into the Upper Nile, their government began to draw together these disparate regions, establishing a new political and cultural hegemony which looked increasingly to a riverine ‘core’. The Egyptians were briefly expelled during the Mahdiyya period (1885–98), but the re-establishment of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium was able to finalize the form of the new state, now bounded by a series of new colonial states created during the last decades of the nineteenth century.

For archaeologists, privileging modern political boundaries, often so arbitrary in their construction, has its obvious problems, particularly in Africa. How do we define areas of study? What is an appropriate scale of analysis? The modern Sudan is vast, with an area of more than 2,500,000km2. Comprising most of Eastern Sudanic Africa the Sudan also represents a region of hugely varied environments, or more properly a series of regions, today ranging from equatorial forests in the south to the empty Sahara in the north. Over the last 10,000 years or so, the natural environment has also varied hugely. In the Early Holocene, much of the region as a whole was a relatively open world of savannah woodlands and grasslands, in which the Sahara was still green. Over millennia this world was gradually to fragment, increasing aridity creating some very distinctive regional environments.

Figure 1.1 Nubia and the Sudan

Some regions where the resources of river and rainland savannahs came together, were to become the focus of a long series of early states, the earliest in sub-Saharan Africa. In the far west of the region, in modern Darfur, the hills and margins of Jebel Marra were also a focus for settlement and political development (McGregor 2001a). Other areas, such as the poorly watered plains of Kordofan, were to become ‘peripheries’ to such regions (Stiansen and Kevane 1998), possessing the resources for survival for their inhabitants, but never really developing their own centres of power.

Over the long term, when looking at the archaeology and history of the Sudan, there are clearly many regional histories and archaeologies, not only those of the better-known riverine core. While the boundaries of the modern Sudan may not seem to easily form a ‘natural’ unit of study they do provide a useful framework for studies of the longer-term, in which regional histories come together, and diverge. What are today often very disparate regions, with distinctive identities, often had much more in common in the past. Familiar distinctions of the modern world, not least between ‘North’ and ‘South’, may become increasingly blurred as we move back through the past. May we discover pasts in which all of the Sudan was the ‘South’? Before moving on to the core of the book, this chapter will briefly look at how archaeology developed, how its character is changing as well as at some potentially important themes which may provide a backdrop to research in this region.

Archaeology in the Middle Nile

As the first Europeans began to enter the region during the early nineteenth century, their perceptions of the region’s past were still largely derived from classical sources. In 1772, James Bruce, explorer of the Blue Nile and Ethiopia, was to first relocate the site of ancient Meroe which had lain on the fringes of the Roman Empire (Bruce 1790). The Napoleonic campaign in Egypt opened the region up to a new wave of European interest in the Nile Valley, often with strong antiquarian concerns. Early travellers who penetrated south of Egypt, for that was the route they usually took, have left us valuable and often perceptive accounts of the Middle Nile, if mainly of parts of the riverine north. With the growth of Egyptological research, more systematic recording of antiquities also began, notably with the Royal Prussian Expedition of 1842–45 (Lepsius 1849–59, 1913). While other forms of archaeology were only very slowly to become established elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, Egyptological interests were to remain at the heart of virtually all research in this region for the best part of a century (Adams 1998b). Systematic research in Nubia began in Egypt with the First Archaeological Survey of Nubia (Reisner 1910; Firth 1912, 1915, 1927), a response to the heightening of the original Aswan Dam in 1908–10, which flooded some 150km of the river valley south of the First Cataract. The archaeological cultures then described by George Reisner have remained with us to today.

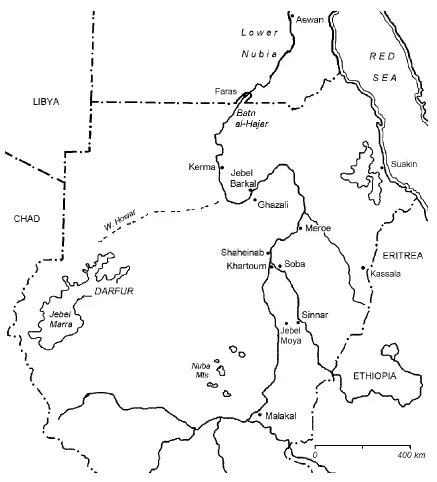

Largely dealing with ‘Nubian’ cultures in contact with pre-Dynastic and Dynastic Egypt, this pioneering work was soon complemented by further expeditions, still largely concentrated on Ancient Egypt’s southern frontier in Lower Nubia. Following a reconnaissance survey of the northern Sudan by the University of Chicago during 1905–06 (Breasted 1908), the first major excavations further south were begun in 1909 at the site of ancient Meroe (Garstang et al. 1911) (Figure 1.2). In 1913, Reisner extended his work into northern Sudan with a series of excavations of the most impressive monumental sites in the region. He began the systematic study of the great Bronze Age centre at Kerma, and major Pharaonic sites of the third and second millennia BC, and Napatan and Meroitic (Kushite) centres of the first millennium BC. His Harvard–Boston Expedition was to dominate research in the region into the 1930s with the investigation of many of the most impressive ancient fortresses, temples and royal cemeteries. In the period 1929–34, the Second Archaeological Survey of Nubia (Emery and Kirwan 1935) extended survey coverage as far south as the Sudanese frontier. The same period also saw further important studies of later prehistoric and Pharaonic sites in Lower Nubia (e.g. Steindorf 1935, 1937) and a preliminary survey of medieval ‘Christian’ remains in Nubia (Monneret de Villard 1935, 1938). Regional surveys in Sudan only began after 1959 in advance of the construction of the Aswan High Dam, extending systematic fieldwork as far south as the southern end of the Batn al-Hajar region, between the Second and Third Cataracts.

Figure 1.2 Major archaeological sites in the Middle Nile

Only very slowly did an interest in prehistoric archaeology develop in the region (Seligman 1914–16, 1916) or in areas outside the sphere of Egyptian influences. A notable early venture was the excavations of Sir Henry Wellcome at Jebel Moya and near Sinnar in the Gezira region in 1910–14 (Addison 1949). The first excavations of the Sudan Antiquities Service in 1944–45 began as rescue excavations within the grounds of Khartoum Hospital (Arkell 1947), discovering the first major Mesolithic/Epipalaeolithic site in this part of Sudanic Africa. This was soon followed by excavations of a Neolithic site at Shaheinab, just north of Khartoum (Arkell 1953). In the same period, Myers (1958, 1960) undertook some limited work on the Neolithic of the Second Cataract region. Such work was not however followed up until the 1970s and until relatively recently only a handful of prehistoric sites have been investigated. While the medieval archaeology of Lower Nubia, especially its churches, had received some attention from the early 1900s, more wide-ranging work was initiated in the early 1950s by the Sudan Antiquities Service with excavations at the medieval townsite of Soba (Shinnie 1961) near Khartoum and the desert monastery of Ghazali (Shinnie and Chittick 1961). Other projects of the 1950s were almost entirely restricted to the clearance of Pharaonic and Kushite monuments and finds-rich tombs.

The High Dam Campaign, at least within Sudanese Nubia, began to see more comprehensive treatment of a wider range of archaeological sites. The Survey of Sudanese Nubia also saw much more detailed survey than was ever carried out in Egyptian Lower Nubia, with the identification of more than a 1,000 sites along some 160km of the Sudanese Nile Valley. While the full results still remain unpublished, the many preliminary reports have vastly increased our knowledge of this region and its cultural history. In its aftermath and the flooding of the whole region beneath Lake Nubia, archaeology has begun to look beyond Lower Nubia and its special relationship with Egypt which was celebrated in more popular syntheses of the time such as Egypt in Nubia (Emery 1965) and Nubia under the Pharaohs (Trigger 1976). The monumental Nubia, Corridor to Africa by W. Y. Adams, published in 1977, provided a first overview of the results of the successive Nubian surveys while also drawing together what was then known about the rest of the Middle Nile.

With the disappearance of Lower Nubia, archaeology has had to move south. Traditional interests in large monumental sites have remained strong, mainly in the Dongola Reach and the Shendi Reach, with an emphasis on the Kushite (Napatan and Meroitic) and medieval (‘Christian’) archaeology. The considerable advances in our knowledge are reflected in recent and valuable syntheses of the archaeology and history of the Kushite (Welsby 1996) and medieval (Welsby 2002a) periods. Other periods remain rather less well-served, despite a growing knowledge of the Neolithic and Bronze Age (Kerma) archaeology in several areas, while interest in the ‘Islamic’ post-medieval period also remains limited (see Adams 1987a; Soghayroun 2000). By the 1990s, a growing awareness has been shown of the importance of continuing field surveys, both in response to direct threats such as road construction (e.g. Mallinson et al. 1996) and dam projects (e.g. Paner 1998, Welsby 2003) as well as to more generalized impact of ‘Development’, beginning to explore areas still otherwise unknown (e.g. Eisa 1999; Welsby 2001a). Such surveys are beginning to open up the potential for more ambitious studies in settlement and landscape archaeology, moving away from traditional more site-focused work.

Archaeology has also slowly begun to penetrate some totally new areas. One major development has been the exploration of parts of northwestern Sudan, notably the Wadi Howar, the now dry river system that once linked Darfur to the Nile (Kropelin 1993). This work has transformed our knowledge of environmental change and the history of human settlement in the region during the Early and Middle Holocene. To the west, some limited fieldwork has been carried out in Darfur (Musa 1986; Ziegert 1994), building on scattered reports of ancient sites and oral traditions associated with them collected during the period of the Condominium (Arkell 1946b, 1959a, 1959b; Balfour Paul 1955). Other recent work has begun to explore the region’s settlement history (Häser 2000) as well as re-examining historical and archaeological records (McGregor 2001a). Surveys and excavations have also begun east of the River Atbara and in the Kassala region (Fattovich 1990; Marks 1991; Sadr 1991). More southerly regions of the Middle and Upper Nile have however, remained largely neglected. The preserve of anthropologists during the Condominium (Wengrow 2003), despite occasional exploratory work by colonial administrators (e.g. Titherington 1923) very few archaeological projects have ever been carried out there (Kleppe 1982b; Mack and Robertshaw 1982) and the long-standing civil war has made this largely impossible for much of the period since Independence. We do however have a wealth of ethnographic descriptions (e.g. Seligman and Seligman 1932), many with a considerable historical value, dating back to the nineteenth century. Our knowledge of the archaeology of different parts of the Sudan is thus very variable, and in many areas still non-existent. Nonetheless, however fragmentary our knowledge, we are beginning to be able to assemble a picture of a larger whole, comprising these disparate regions.

Changing perspectives?

A century after the first pioneering projects began to work in northern Nubia, much has changed. Nubian archaeology is not just about Lower Nubia and the margins of Egypt. We are increasingly in a position to look beyond Lower Nubia, and begin to appreciate its place within wider macro-regional contexts. The cultures of Lower Nubia, once perceived as discrete entities, can increasingly be related to much more widespread traditions encountered across much of the northern Sudan. The results of new surveys in Upper Nubia are also now overshadowing the impressive archaeology of the north. Where Late Neolithic and Bronze Age cemeteries in Lower Nubia rarely held more than 100 burials, those of the Dongola Reach hold thousands. While Lower Nubian sites are often rich in imported Egyptian artefacts, their southern counterparts may display a different but often far greater wealth in indigenous materials. Where earlier generations of archaeologists were so impressed by the archaeological wealth of Lower Nubia, it is becoming clear that the region was very often peripheral to much richer and more densely populated regions further south. Such wealth as it did display and many of the more distinctive cultural features encountered there may be related to its proximity to Egypt, as a corridor linking sub-Saharan Africa to the North.

Such changing perspectives may also be accompanied by a shift away from many of the traditional preoccupations of archaeologists working in this region. Largely coming from Egyptological backgrounds, Egyptocentrism has long been pervasive. The pioneering generations, reflecting the attitudes of the day, could consider Nubian history might be ‘hardly more than an account of its use or neglect by Egypt’ (Reisner 1910: 348). Much early research in the Middle Nile was concerned with the ‘civilizing mission’ of Pharaonic Egypt and the ‘North’ in Wretched Kush (Smith 2003), very often echoing the rhetoric of Colonial governments. Such attitudes should not be surprising in an era when any evidence for African cultural achievements – Great Zimbabwe being another case in point – was only explicable in terms of external stimuli. That indigenous African cultures might be of interest in their own right was a largely foreign idea.

When the monuments and cultural achievements of Bronze Age Kerma were first discovered they were attributed largely to an Egyptian presence. Such Egyptocentrism has proved remarkably resilient. Even today, explanations for the rise of Sudanese states still look to Egyptian influences (Morkot 2003). Narratives of the Pharaonic state’s conquest of Nubia are still commonly implicit in celebrations of Imperial values and the triumphs of ‘civilization’ (Patterson 1997). There remains an enduring fascination with the temples and fortresses of ‘great’ Pharaohs, while the brutal histories of military conquest and destruction which underpinned their ‘achievements’ (Kemp 1989: 318–9) remain rather less closely observed. That much of Egypt’s interaction with Nubia was at this level tends to be ignored. Chronologies of Bronze Age Nubia still remain structured around the historical frameworks of Pharaonic Egypt. Unfamiliar cultural forms are still simply described as ‘African’, as if nothing more needs to be known about them.

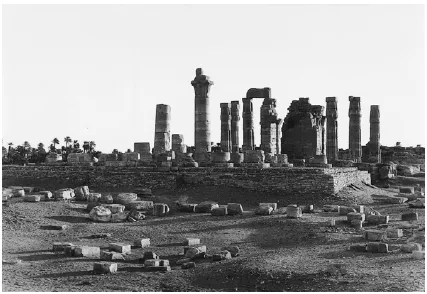

Prior to the 1960s, they were few voices which suggested that it might be of interest to look beyond the Egyptianized temples and monuments in order to recover other histories in the region (Figure 1.3). O.G.S. Crawford was one notable early champion of a more broad-ranging archaeology, which he forcefully argued in a famous essay ‘People without a history’ in the journal Antiquity (Crawford 1948). As he observed , the ‘Sudanese . . . do not need to be told that there is such a thing as Sudanese, as distinct from Egyptian archaeology, . . . to many others this is a new idea’. Provocatively, he went on to suggest that ‘the excavation of a Nilotic mound-site is more suitable to be undertaken at the present moment than that of yet another Egyptian temple’ (1948: 12). More than half a century later, no more than a few trial trenches have been excavated in any such mounds (e.g. Kleppe 1982b and c). Temples continue to be cleared.

This Egyptological legacy has certainly also been an important factor in isolating archaeological research in the Sudan from that of the fledgling ‘African’ archaeology, especially where it might have shared interests and concerns with other parts of Sudanic Africa. That the Sudan was a region which was somehow fundamentally different from other parts of Sudanic Africa had also become a more widely held perception since Egyptian rule penetrated the region. From the early twentieth century prominent anthropologists like Herskovits (1924) would suggest that it formed a culturally and politically distinct ‘culture area’. It is only relatively recently that historians have begun to argue for a realignment of research which again attempts to locate the Middle Nile within its wider Sudanic context (e.g. Horowitz 1967; Hasan and Doornbos 1979; O’Fahey and Spaulding 1974). How its ‘Arab’ and Islamic identities – which distinguished it from the ‘African’ – were also created in the post-medieval period has also become better understood. Popular perceptions, and politics, all too often still perceive an ‘Arab’ north and ‘African’ south as somehow a natural and timeless condition, rather than a creation of relatively recent history.

Figure 1.3 New Kingdom temple at Soleb.

The necessity for broader Sudanic perspectives also begins to be more obvious as research moves away from its traditional northern riverine foci. The results of recent research in the Wadi Howar demand more wide-ranging perspectives, exploring linkages between the Nile Valley, the Chad Basin and the wider Sahara. For millennia it was an important corridor linking the Nile and the West, remaining so until such links were largely broken by the encroaching desert during the third and second millennia BC. To the west, Darfur with the Jebel Marra massif in its centre, marks another crucial area on the watershed between the Chad Basin and the Nile Basin, which has also been a frontier zone for millennia (Musa 1986). Through Kordofan it was to provide a link between central and Eastern Sudan and West Africa.

RESEARCH THEMES

Regional histories and changing environments

One key theme which lies at the heart of any construction of long-term histories of the Middle and Upper Niles must be the relationships between its many regions, and how they may have changed over time. An acknowledgement of the existence of the varied histories of different regions is indeed fundamental to any attempt to write an archaeology of the Sudan, a political entity of such recent invention. Archaeological cultures, often manifestations of political entities, were often restricted to relatively limited areas, especially in riverine northern and central Sudan. These were not, however, isolated from neighbouring areas. Over time the connections and linkages between different regions were also dynamic and shifting. In the favourable environmental conditions of the Early Holocene, populations, while sparse, were potentially part of far more extensive worlds extending over the vast savannahs in what is now Sudanic and Sahelian Africa. With ongoing desiccation, new constraints were imposed. One result of this may have been the development of increasingly distinct regional cultural traditions, not least in what was to become the linear oasis of the Nubian corridor running through the Sahara. Such narrowing options may have become more important in the north. Elsewhere, they may have been balanced by expanding horizons. In the South, as drier conditions established more favourable savannah environments new opportunities may have been created for new ways of life, while new connections were also being established, both to the West and with Eastern Africa.

Such changing environments were clearly implicated in other long-term processes. In riverine regions, there has been a progressive shift towards the south of major political foci (Anderson and Johnson 1988), undoubtedly related to increasing arid conditions spreading from the north. During the Bronze Age, the first kingdoms of the region were established in Dongola Reach. By the mid-first millennium BC, the focus had shifted to the Shendi Reach at Meroe (Figure 1.4). A thousand years later, probably the greatest of the medieval Nubian kingdoms was centred at Soba, near the confluence of the Niles. By 1600, the heart of the Funj Sultanate lay even further south along the Blue Nile at Sinnar.

Over the millennia people engaged in complex interactions with their environments, both as victims of environmental decline as well as agents of landscape change. Major developments are likely to have occurred with the innovations associated with the ‘Neolithic’, first with the introduction of domesticated livestock, and later with the shift from the exploitation of wild plant resources to the management and cultivation...