1

ARCHAEOLOGY AND COMPUTERS

The decades since the 1960s have seen extensive and varied changes within archaeology and its relationships with other disciplines. One of the most profound developments has been the explicit discussion of theory and the acceptance of the central role of theory within archaeological practice. The theoretical framework of the discipline has been almost continuously reassessed and reworked, initially with the challenge to the traditional culture-historical approach by processual archaeology and, in turn, by the rise of post-processualism. Encompassing these changes, and influencing them in a myriad of complex ways, have been the wider social and intellectual discussions loosely based around understandings of modernism and postmodernism. Embedded within this discourse, and of particular interest to this background chapter, are the information and communications revolution and the associated rise of digital technologies. Here, rather than providing a descriptive historical account of the development of archaeological computing as an insular phenomenon, I think it is of more interest to position these disciplinary developments within the ebb and flow of the wider concerns and debates. The main themes to emerge are the potential of computers as active agents for thought rather than as just passive tools, and the symbiotic relationship between the development of digital technologies and archaeological theory, both of which incorporate a trend towards the concept of increasing contextualism, complexity and data-rich environments.

Data and theory

The word ‘data’ is now in daily use in many different contexts and almost synonymous with the use of computers. That archaeologists ‘collect data’ and ‘feed them into a computer’ are almost taken as givens within everyday conversation to such an extent that to state that both archaeology and computers depend upon data is a meaningless truism. We need to probe a little deeper. What do we mean by archaeological data? Is there a direct relationship between them and data suitable for a computer? What is the relationship between both of these and the archaeological record, material culture, archaeological theory, interpretation, methodologies, analysis and meaning? Where do other concepts often associated with computing, such as ‘technology’, ‘objectivity’ and ‘scientific’, fit into the practice of archaeology and, specifically, what has been claimed as the sub-discipline of archaeological computing?

In essence the discussion concerning data has been whether they fit the Latin meaning of the word and are ‘things given’ or whether they are ‘things made’. This is not an issue in isolation but one that exists within wider philosophical and theoretical schemes of how we move from the empirical reality of the archaeological record through interpretation towards explanations of the ‘past’. It is useful when discussing the changing views of data to maintain the now commonplace historical development from culture-historical archaeology, through processualism to post-processualism (Trigger 1989), although at the same time acknowledging that this is by no means an evolutionary process and that what follows is a considerable simplification of the complexities of the arguments (Hodder 1986).

In general, archaeology pre-1960s was grounded in the empirical description of material evidence which included a strong notion of common sense and a belief that a body of data would ‘speak for itself’. Patterns would emerge from the study of often large collections of descriptive data so that pottery, tools and houses made sense through being grouped together as assemblages according to observed traits, which were then given spatial and chronological definition through the Childean concept of cultures. Culture-history was written, often by invoking diffusionism to explain the spatial and temporal connections within the data, a classic example being the spread of early Neolithic cultures across Europe (Childe 1929). Because of the lack of explicit theory at the time, except by a distinguished few, data were taken as given by most archaeologists and the process of observation, recording and interpretation needed little, if any, justification.

Changes in the form of the ‘new’ archaeology (now processualism) heralded the Scientific Method and a rejection of the perceived subjectivity of empiricism. Set within a wider move towards positivism, epitomised by the philosophy of the natural sciences (Hempel 1965), central to processual archaeology was a belief in objectivity through the systematic observation, measuring and recording of data using quantitative methodologies. Objectivity was possible by separating theory from practice so that objective data existed and could be measured by an observing subject. Whereas the previous link between data and theory was inductive, i.e. an unbiased collection of ‘all’ data will produce theory, the new paradigm had at its core hypothetico-deductive reasoning. In this scheme, knowledge is accumulated by the testing of explicit hypotheses (often by the use of formal statistical tests of significance) against data collected on the basis of being relevant to the analysis. This was seen as being efficient and critical to the advancement of archaeology as a scientific discipline. The wider implication of adopting the Scientific Method, and thus coming into line with the natural sciences, was the possibility of creating a global archaeology united by standard analytical methodologies (Clarke 1968) that could be applied on any set of data to establish cross-cultural generalisations and even ‘laws’.

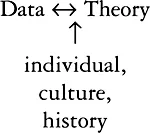

Growing disillusionment with this detached scientific view that failed to incorporate ‘the social’ (both past and present) gave rise to post-processual archaeologies and the rejection of the Scientific Method and its proposed foundation of objectivity (Lucas 1995). Instead, the relationship between the archaeologist and the archaeological record is now seen as an interpretative discourse, sometimes described as the hermeneutic spiral, between subject and object. This does not recover meaning inherent within the object but produces a theorised version of it through the subject-object reflexive relationship. Shanks and Tilley present this argument in detail (1987) and conclude that data are a theoretical appropriation of the archaeological record; it is the theoretical object and not the real object that archaeologists work with. Theoretical and real objects are not the same and exist in relative autonomy from each other. The former, the theoretical objects that we work with, are cultural products of the present formed in given circumstances, i.e. the social and cultural context of the archaeologist, with given purposes in mind, i.e. the present analysis, (ibid.: 110). This is summarised by Hodder (1986: 14) as a changing relationship between data and theory, from the culture-historical one way flow of Data → Theory, through the simplistic processual hypothesis-testing of Data ↔ Theory to the post-processual complexities and uncertainties of

A ‘subjective’ present of relativism, as opposed to an ‘objective’ past of science, accepts that data are not objective but are theoretical in themselves, resulting in a whole range of possible archaeologies, i.e. interpretative archaeologies (Hodder et al. 1995). It follows, therefore, that testing in the sense of processual hypothesis-testing is not valid as there is nothing independent of theory to test. While this makes testing for statistical significance redundant, and this was a mainstay of the Hypothetico-Deductive method, it does not necessarily mean the end of statistics in archaeology, which can still be useful for pattern recognition and description within the interpretative cycle. Despite statistics playing a central role in the early days of archaeological computing and in the formulation of processual theory, as shown by Shanks and Tilley (1987) they can still be important analytical tools depending upon the theoretical framework within which they are used. Processual archaeology was rooted in quantification to such an extent that, it was argued, data could be standardised by unbiased collection and thus rendered comparable. Their recording was determined by categories of analysis designed to enable calculations and, therefore, the philosophy gave primacy to the general methodology rather than to the particularities of the data (ibid.: 56).

Nowadays statistics are just one aspect of archaeological computing, although the need for the quantification of data, in its broadest sense, is still critical to the use of the technology. To be used in a computer, and processed in some way, data have to be rendered digital and this will require a structural link between the data as theoretical object and the data as stored digital bits and bytes. This link is especially obvious when using software such as databases, statistical and spreadsheets which require a data structure to be made explicit. Much archaeological analysis involves being able to compare and contrast different aspects of data which depends on working with counts and categories which themselves depend on making decisions based on observation during data collection. Making decisions implies a subjective/objective tension, although an either/or situation is often not helpful or realistic within the everyday practices of archaeology. In his historical account of objectivity and subjectivity in archaeology, Rowlands (1984) traces the former back through Hempel to the Enlightenment ideals of the eighteenth century based on the aim of explanation. In contrast, subjectivity, as epitomised by the humanist approach of Collingwood in his classic book The Idea of History, stems ultimately from German romantic idealism and aims at understanding. Both, according to Rowlands (ibid.: 113), are based on outmoded categories of thought which need to be dissolved and integrated within contemporary archaeology. So while theoretical discussions are a necessary framework for archaeology, and processual and post-processual positions are useful extremes for focusing an argument, most practising archaeologists occupy a pragmatic middle ground and use a range of methods and approaches. Data collection and interpretation are still the bread and butter for most working archaeologists who aim for both explanation and understanding.

Traditionally data collection involves first the identification and then the measurement of ‘significant’ attributes (which must have two or more states to be measurable). While the former of these two stages is embedded within the theory outlined above, there are well-established methods for the latter. It has been recognised for many years that computerisation forces an explicit description of data structure through the identification of measurable attributes and the relationships between them. While it has been argued here that this is not an objective process, it need not be totally arbitrary. By recognising that the concepts of ‘precision’ and ‘accuracy’ are different to objectivity, and that they can both be applied to data collection, Richards and Ryan (1985: 16) have identified four factors underlying the collection of data to enable computerisation:

- The avoidance of duplication in the selection of attributes;

- The separation of attributes from attribute states;

Both of these are characteristics of classification which require an explicit logic reflected in the eventual structure of the data (Forsyth 2000). - The identification of deliberate human selection, for example, the height of a pot may be considered to be a reasonable attribute to record but not the number of clay molecules;

- The frame of reference of the study so that the presence or absence of a pot may be suitable for a study of funerary ritual but a study of a pottery assemblage will require a single pot to have many attributes such as height, width, decoration, etc.

Following these principles during the construction of a database, for example, does not make the data any more ‘objective’ although it does make them precise and accurate within the data structure made explicit through the process of computerisation.

Applying similar concepts of precision and accuracy, data used within a quantitative analysis can be classified into variables using the long-accepted levels of measurement of nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio (Stevens 1946). In this scheme the first two levels are qualitative and involve a subjective categorisation of the data while the other two are quantitative, i.e. objective measurements (or at least physical measurements: the choice of what to measure is not necessarily objective). Again there are theoretical considerations of importance here when trying to relate this scheme to archaeological data and subsequent interpretation. Not least is the danger of spurious accuracy as illustrated by Spaulding (1982) who argues for the importance of nominal level variables as a closer correlate to human decision-making processes (past and present) which involve concepts and categories such as ‘big’ and ‘small’ rather than accurate absolute measurements to three decimal places. Another consideration within data collection is the issue of scale, an issue with particularly important ramifications for spatial data where analysis should take account of, and be based upon, the scale of collection.

A discussion of data would not be complete without mentioning the word ‘fact’, usually defined as ‘something known to be true’ and thus originating within the positivist scientific tradition. The discussion on objectivity/subjectivity above raises obvious problems when considering the status of facts in archaeology, problems that have been recognised for some time. Concerning the historical disciplines generally, Collingwood (1946: 132) discusses the false analogy between ‘scientific facts’ and ‘historical facts’. The former are based on observation and verified through experimentation whereas the latter are based on inference arrived at through a process of interpretation using accepted disciplinary rules and assumptions. Another historian, Braudel (1980: 42), when discussing the potential impact of computers (‘calculating machines’) in the 1960s and the emergence of related schemes of quantification (‘social mathematics’), identifies three different kinds of facts: necessary facts are those that can be proven within the scientific tradition, contingent facts are based on an associated probability, and conditional facts are neither of the above but behave under known constraints or rules. These two examples suggest that the use of ‘facts’ is likely to be contentious within archaeology although, because it is such a broad discipline, the word is more acceptably applied in some areas than others. Some scientific archaeology does provide data derived from direct observation that is capable of reproduction through experimentation and would justify being called factual evidence, therefore, by most archaeologists; the chemical analysis of materials for example.

A term that is becoming increasingly important is ‘information’, as reflected in the suggested change of ‘computers’ into the more generic Information Technologies. Associated with this are the claims for wider social and cultural changes towards an Information Society (Webster 1995), discussed more fully in Chapter 8. While ‘data’ retains a generally perceived element of ‘scientific objectivity’ based on an idea of direct measurement, ‘information’ is a softer, all encompassing term seen as representing knowledge at any and all levels of interpretation.

Modelling the past

Another central plank of processual methodology was the use of models and the concept of modelling. Again, these ideas were explored in related disciplines especially within the early adoption of computers and the required quantification of data to enable the application of computing. For example, modelling was particularly important within Systems Theory thinking across a range of subjects which sought to reduce human reasoning to formal rule-based systems of logic (Bloomfield 1986). Braudel (1980: 40) saw models as central to the process of historical analysis, ‘systems of explanation’ especially useful within a structuralist framework so that ‘laws’ underlying cultural behaviour could be expressed mathematically. He classified the types of model likely to be useful within history as a series of opposites: simple or complex, qualitative or quantitative, static or dynamic, mechanical or statistical.

Models and modelling have been most thoroughly explored in archaeology by Clarke (1972). Although these are often ill-defined terms that have been used in many different ways in archaeology, the concept of models is useful here to develop the argument concerning the relationship between data, theory and computers. At a basic level of agreement, a model is a simplification of something more complex to enable understanding. Clarke saw models as idealised representations of observations (ibid.: 2) which in general terms acted as devices for the construction and development of theory, and more specifically were heuristic, visualising, comparative, organisational and explanatory devices. Within this same definition, models are structured, although selectively, and operate within specified fields of interest. Clarke claimed that these three qualities open the possibility of more than one model for any one situation making them pluralist and, therefore, not ‘true’ but a part of the hypothesis generation and testing procedure which resulted in explanation (ibid.: 4). He then went on to provide a detailed classification of models ranging from reconstructions of prehistoric roundhouses to statistical formulae representing an abstraction of hunter-gatherer social structure. Voorrips (1987) simplified the classification emphasising the difference between empirical and formal models with combinations of the two. The roundhouse reconstruction, artefact drawings or site plans are empirical models based on direct observation, whereas formal models are abstract simplifications of a complex reality such as simulations of social relationships.

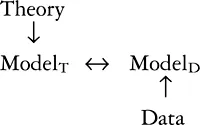

It is formal modelling which is useful here in providing the explanatory argumentation that relates data to theory, as suggested by Read (1990). This link, or interaction as it is a two-way process, is created by the comparison of two models, a theoretical model, ModelT, and a data model, ModelD, as shown here (ibid.: 34):

Both are abstractions: ModelT is structured with reference to the abstractly defined relationships within the theory while ModelD is an idealisation of empirical conditions with reference to the data in question. Correspondence between the two models represents an explanatory argument while a mismatch between the models causes problems in interpretation. The potential for mismatch is created by ModelD constructs being rigorously defined (as in the arguments for precision and accuracy above) whereas ModelT constructs are likely to be less systematic, as Cowgill (1986) suggests ‘archaeological theory is rarely couched in mathematical terms’.

Models are not confined to processual ideas of explanation and knowledge acquisition. Shanks and Tilley (1987) see them as heuristic fictions used to organise the archaeological record and make it meaningful by extracting what is most pertinent to understanding. Here the positivist and post-positivist use of models converge somewhat, with both arguing that the power of modelling is in moving from what is observable, material culture or its theoretical object equivalents...