1

Concentration camp memorial sites

‘It is a fact that we either want to learn from the past, or we condemn ourselves to repeating old mistakes. The facts of concentration camp conditions, the causes of the atrocities there, the assessment of degrees of guilt and the naming of the victims are, taken together, important areas of information which must never be repressed nor forgotten.’

(Schafft and Zeidler 1996:7)

Sites of crime, sites of memory

Concentration camps have long been a method of terrorizing and neutralizing groups identified as ‘the enemy’. The very first of these were set up in Cuba in 1896 (campos de concentración), where the Spanish governor ‘concentrated’ Cuban rebels in camps in an attempt to break their resistance to Spanish colonial rule. In 1900, the British established ‘concentration camps’ in South Africa during the Boer War. Arguably, it was during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933) that the first concentration camps were created in Germany. Reich President Ebert used emergency decrees in 1923 to quash political unrest: communists were taken into ‘protective custody’ in former prisoner-of-war (POW) camps. These camps, and those set up in the early 1920s in Stargard and Cottbus-Sielow to ‘concentrate’ Eastern European Jews who had fled from the Poles and Russians, were in some very limited respects precursors to the Nazi camps (Drobisch and Wieland 1993:16–21). Although conditions in the Weimar Republic camps could be poor, they were not murderous; and they were not a typical feature of the Weimar political system. It was the Nazis who institutionalized, perfected and made a murderous machine of the concentration camp system. After the arson attempt on the Reichstag on 27 February 1933—which the Nazis blamed on the communists—the regime set about incarcerating communists in prisons and camps. The earliest camps were ‘ad hoc affairs, set up by local Party bosses, the police and the SA’ (Burleigh 2000:198–9). The most notorious ‘wild’ SA camp was probably that at Oranienburg (Morsch 1994). But it was under the SS that the concentration camp system was to be developed into a monstrous instrument. The first SS-run camp to be established was Dachau, opened in March 1933. In the course of the 1930s, the whole concentration camp empire was coordinated and centralized by SS leader Heinrich Himmler, who placed it under the authority of Theodor Eicke. Eicke had become Commandant at Dachau in June 1933. He was responsible for building up the notorious Death’s Head units, from which camp guards were recruited. Other camps followed Dachau: the main ones were Sachsenhausen (1936), Buchenwald (1937), Flossenbürg (1938), Neuengamme (1938) and Ravensbrück (1938–1939), the latter for women prisoners. The new camp at Sachsenhausen was valuable because of its proximity to Berlin—it could be used to incarcerate ‘enemies of the Reich’ quickly in case of war. But economic factors played an increasingly central role in the choice and development of sites, as the SS sought to turn the camp empire into a thriving economic concern. Thus prisoners at Sachsenhausen slaved away in nearby brickworks; bricks were needed to fuel Speer’s rebuilding programme in Berlin. In Flossenbürg prisoners were put to work in quarries. Many satellite camps were set up at the site of armaments firms.

The number of inmates rose rapidly in the course of the first five years Hitler was in power. The composition of the inmate population changed over time and was different from camp to camp. A few generalizations, however, can be made. Prior to 1937, it was principally political opponents of Nazism who had been held—social democrats and communists, but also ‘dissident’ members of the clergy; among the communists and social democrats, however, were many Jews. Increasingly, racial politics played a part in reasons for internment. In 1938, the Nazis stepped up their campaign of terror against Jews. In the course of the ‘Action Workshy Reich’, and subsequent to the Reichskristallnacht pogrom of 9–10 November 1938, thousands of Jews were detained in the concentration camps, many of them, however, only for a short period. Thus between April and December 1938, 13,687 Jews were sent to Buchenwald by the Criminal Police and Gestapo (GB 1999:76). The sharpening of the laws against homosexuality in 1935 led to the imprisonment of homosexuals in the concentration camps, although their number remained relatively low. Another group to suffer incarceration was the Sinti and Roma, many of whom were arrested in April and July 1938 along with the so-called ‘asocials’ in line with the ‘Basic Ruling on the Preventative Combating of Crime’ (Wippermann 1999:50). Jehovah’s Witnesses, who refused allegiance to Hitler and military service, were interned in concentration camps as of 1935, and particularly from 1937: by the end of 1938, the number of Jehovah’s Witnesses in Buchenwald had reached 477 (GB 1999:70).

Following the outbreak of war in 1939, more and more foreign nationals from the occupied countries—Czechs, Poles, Dutch, Russians, French—were deported to the concentration camps within Germany, either as hostages, because of their role or alleged role in resistance, as prisoners of war, because they were Jews or in other ways ‘racially inferior’, or for purposes of slave labour (often motives were mixed). In 1942, as the Nazis stepped up their programme to make Germany ‘Jew-free’ and, ultimately, exterminate them in the ‘Final Solution’, most Jews in concentration camps within Germany were deported to work or annihilation camps in Poland, such as Auschwitz. Those considered too weak for deportation were killed: thus many of Buchenwald’s Jews were gassed at Bernburg, a euthanasia centre (GB 1999:128). The ‘detention camp’ at Bergen-Belsen, set up in April 1943, was something of an exception: it was used to hold ‘exchange Jews’, Jews of foreign nationality whom the Nazis planned to exchange for German POWs. In the course of 1944, it developed into a full concentration camp. As the Red Army pushed the Wehrmacht back in 1944 and 1945, the Nazis were forced to evacuate the work and annihilation camps in the occupied territories. Thousands of Jews died during the transport to Buchenwald, Dachau and other camps. In the overcrowded camps in Germany, the mortality rate in the final months of the war—as a result of hunger, disease and murder—was catastrophically high. As the Allies approached the concentration camps, further evacuations, or ‘death marches’, claimed the lives of thousands. In a terrible error of 3 May 1945, British bombers attacked two ships in Lübeck Bay that were full of evacuated prisoners. More than 7,000 of them died (see AIN 1995).

Generally speaking, the concentration camps within Germany were not centres of industrialized genocide, in contrast to the annihilation camps in Nazi-occupied Poland where the ‘Final Solution’ was for the most part carried out. But systematic slaughters and innumerable gratuitous killings were still the norm. One of the most notorious massacres was the methodical execution of Soviet POWs. With the cooperation and collaboration of the Wehrmacht, political commissars, state and Communist Party functionaries and other ‘undesirable elements’ among the Soviet POWs were rounded up, deported to Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald, and then killed in their thousands by means of a specially constructed apparatus which delivered a fatal shot to the neck. Eight thousand Soviet soldiers died in this way at Buchenwald alone between the summer of 1941 and the summer of 1942. Many concentration camp prisoners died when they were deported to Nazi extermination centres in Poland. Others perished as a result of labour, starvation and disease in the concentration camps. Thus, all in all, about 50,000 people lost their lives at Bergen-Belsen, 56,000 at Buchenwald. Those who survived till liberation died soon afterwards, or lived with lifelong traumas—victims of a concentration camp system notorious for its injustice, exploitation and murderous brutality.

After the end of the war, Auschwitz-Birkenau, site of the mass murder of over a million Jews, lay beyond the East German border in Poland, and far enough away from West Germany for its citizens to be tempted to forget it had once existed—at least until the 1963–1965 Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt. But the former camps at Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Flossenbürg and Neuengamme became potential sites of memory for West Germans; Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald and Ravensbrück potential sites of memory for East Germans. More than anything else, the post-war treatment of these sites was going to be a measure of the preparedness of Germans to face up to the criminality of National Socialism. This chapter will demonstrate that, while memorial sites were set up at the former camps in both Germanys (more resolutely in East Germany, and also with more staff), these sites were subjected to the process of divided and one-sided memory outlined in the Introduction. Ideology, with its attendant overemphases, distortions and omissions, made its mark on forms of representation at the memorial sites (more so in East Germany). From the immediate post-1945 period onwards, more-over, most former camps were subjected to a process of refunctionalization, and thus of historical estrangement. Only as of the 1980s, but particularly after unification, did a concern to create a more rounded picture of camp life, of victims and perpetrators, and to recover the original topographies become noticeable. This concern has resulted in significant changes to the exhibitions at all concentration camp memorial sites, especially in eastern Germany, where the ideological imprint was more pronounced than in the FRG. It has also resulted in an ‘expansion’ of the memorial sites, as they reach out to encompass the original extent of the camps—the inclusive model of memory at work.

Putting to a new use

After liberating the camps, the Allies did, to a degree, confront Germans with the atrocities there, as, for example, when the Americans made the citizens of Weimar face piles of corpses at Buchenwald. In November 1945, moreover, the Americans were instrumental in arranging for a small exhibition on SS crimes to be shown at Dachau, concurrently with the staging of the first Dachau Trial. But the Allies also set a precedent of erasing traces and of new utilization. In the case of the burning down of prisoners’ huts by the British in Bergen-Belsen, such erasure was a necessary response to the danger of typhus. Faced with the need to intern or relocate so many people, moreover, the Allies cannot readily be blamed for turning the former concentration camps into internment or relocation camps. Practical exigencies were paramount, and the concentration camps in any case were associated with such dire suffering that it might, at first, have seemed perverse to want to ‘preserve’ them. With hindsight, however, it is unfortunate that the Allies inscribed new historical narratives into the sites, because to a degree these overwrote the first narrative. There was an additional problem. While some of these narratives, as in the case of the imprisonment of SS men by the Western Allies, appeared at least to stand in punitive relation to National Socialist crimes, others created new legacies of injustice. Thus at ‘Special Camps’ set up by the Soviets in Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald inter alia, thousands of Germans died of malnutrition and disease after 1945. This was a narrative East Germans were not able to relate until 1990, but when it was related, there was a danger it would divert the focus away from the atrocities of the concentration camps (see Chapter Two). Even when the former concentration camps had become well established as memorial sites, the Allies continued to use parts of them for military purposes, particularly so in East Germany. Ravensbrück Memorial Site, for instance, opened in September 1959, was perched on the lakeside at the edge of the original camp topography, while the Soviets continued to use the area of the former camp huts, not least for tanks and as materials depots, right up to unification in 1990. Their officers lived in the yellow-painted settlement formerly used by the SS administration and camp guards, and a number of new buildings were constructed for canteen, commercial, industrial and living purposes. A whole new military culture encrusted itself around the fig-leaf memorial site. In Dachau in West Germany, too, the area of the SS camp remained under US military control until 1972, including the camp’s entrancebuilding and the so-called Bunker, a set of cells in which prominent or significant prisoners had been interned. After this, the Bavarian riot police took over these areas, sealing off the original entrance to Dachau camp.

The use of parts of the camps by the Allies continued beyond their immediate post-war remit. The resulting constriction of the memorial sites served to trivialize the past; memorial site visitors left Ravensbrück and Dachau with the impression of an altogether smaller camp complex. The Germans were also quick to allocate other uses to the camps, and here the concern was both one of practicality, and one of hiding an uncomfortable past. When Flossenbürg and Dachau were passed over to Bavaria, the Bavarian Regional Parliament ruled on 29 April 1948 that they should be used to house Germans expelled inter alia from the Sudetenland (in Czechoslovakia). Within the space of a few years, Flossenbürg had seen a series of different occupants come and go. It thus continued to function as a ‘transit’ camp, a role which it had had in the Third Reich. After liberation in 1945, it was used to imprison SS men. From 1946 to 1947, it was used as a United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration camp, housing displaced persons (DPs) such as former concentration camp inmates, forced labourers and prisoners of war. As of 1947–1948, it served as collection camp for Germans who had been forced to leave the Sudetenland and other areas east of the Oder and Neiße rivers. In the mid-1950s, the community of Flossenbürg tore down the former concentration camp huts and sold the ground to the expellees. Family homes replaced the traces of terror as the expellees became a permanent feature of the landscape. The presence of these expellees was a political and psychological statement to the effect that the Germans chose to empathize with this group of victims, rather than with the victims for whose sufferings the Germans themselves had been responsible. The sense of injustice at the expulsion from and loss of the eastern territories was inscribed stubbornly over the narrative of National Socialist perpetration. Street names, such as Sudeten Street and Silesian Way, functioned as signposts to this injustice. A similar practice of street-naming was established near Dachau’s former concentration camp (see Chapter Three).

A different, yet comparable situation, obtained at Neuengamme. In 1948, the city of Hamburg took over the former camp site from the British and promptly turned a significant part of it into a massive prison [Plate 1.1]. The former SS main guard house together with a watchtower became the entrance to this new ‘Institution for the Implementation of Justice’ (Justizvollzugsanstalt), and the crematorium and a number of wooden huts were torn down to make way for it. A year before, in 1947, one legal councillor had opined that setting up a model prison would represent an ‘act of making good’, a means of ‘restoring Hamburg’s honour and reputation’ (quoted in FR, 8 May 1997). Certainly the prison was well intended, but it also represented a rather hurried and defensive attempt at demonstrating self-improvement. Hamburg sought to avoid confronting its past by asserting that it was now operating a penal system in accordance with the highest standards of justice. Worse, there was an all too pervasive implication that the problem under the National Socialists had been the inhumane way the camp was run. Of course this had been one of the problems, indeed the main one. But the other problem had been that the people incarcerated under Hitler were innocent. It was not just the penal environment that was criminal in Neuengamme camp, but the fact that people had been imprisoned there in the first place.

Plate 1.1 Neuengamme Memorial Site. In the background, a prison built after the war by the City of Hamburg.

When, in 1991, the building of a supermarket at Ravensbrück hit the headlines, there was a national outcry—not least from west Germans keen to point the finger at east Germans. Yet in 1991 the prison still stood at Neuengamme despite years of protest from former camp prisoners, and it seemed set to stay; indeed a second prison, a youth detention centre, had been added in 1970. Moreover, in 1973, a wharf company was allowed to lease the east wing of the former concentration camp’s clinker brick factory, and even to use a canal built by camp prisoners. Commercial use was no exception in the West. At Flossenbürg, the SS canteen, first used as a cinema after 1945, became a restaurant. The Upper Palatinate Stone Industry used the quarry area, with its huts and SS administrative buildings, as of 1950; the camp laundry-room and kitchen, together with the roll-call area, was used for years by the French firm Alcatel. In line with this commercial use, new factories were built on the site in the 1970s and 1980s. Nor did the GDR shy from industrial use. One firm (VEB Spezialbau) built technical equipment for the Stasi and SED near Ravensbrück. In Buchenwald, an agricultural collective kept grain in a former concentration camp building until 1985. Both the GDR and FRG used camp sites for military purposes. Traces of the presence of the GDR’s National People’s Army (Nationale Volksarmee) at Sachsenhausen are still visible today, and the West German army (Bundeswehr) used the concentration camp at Esterwegen, where the publicist Carl von Ossietzsky had been held, as a depot. Other institutions also made use of former camp sites. In Oranienburg (East Germany), the concentration camp where the anarchist writer Erich Mühsam was murdered vanished altogether under a new building for the police; the camp at Moringen (West Germany) was smothered by a regional hospital and clinics as of 1955.

The uses described above reduced or even removed the space available for memorialization. In giving the camp sites new functions, the GDR and FRG created new associations for these sites, linking them to the present or future, thus stifling associations with the past. Indeed the former sites were used as a vehicle for demonstrating the selftransformational energies of the perpetrator nation, at the cost of empathy with the victims. West German camp memorial sites became the focus of a constant struggle, principally led by organizations representing camp victims, to ‘win back’ those areas of the camps now used by industry or state institutions. Victims insisted on the revisualization of the true parameters of their agonies. They thus soon found themselves engaged in a new struggle against discrimination, this time in the area of memory. While such protest often went unheard, it could not be articulated, or not to the same degree, in East Germany. The reason for this was the centralized running of Buchenwald, Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen, and the state cooption and control of the streamlined victims’ organization.

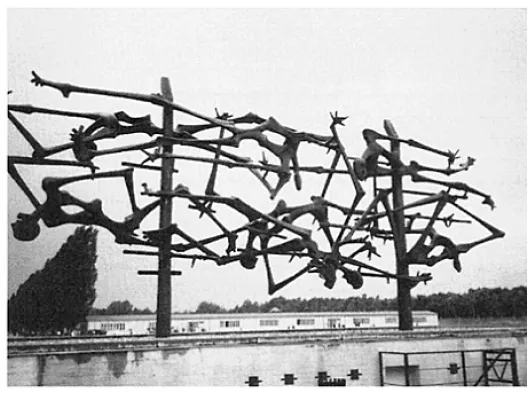

The memorial sites in the West

Against this background, it will come as no surprise that the areas reserved for remembering the National Socialist history of the camps were themselves shaped in accordance with certain ‘diversionary’ tactics. In the case of West Germany, forms of remembering were often heavily Christianized. This was particularly so at Dachau Memorial Site. In 1960, in front of 50,000 people, the ‘Chapel of Christ’s Fear of Death’ was dedicated. In 1963, the foundation-stone was laid for a Carmelite Monastery. Construction of the Protestant Church of Conciliation began in 1965. Given that these confessional buildings were constructed on the site of the former camp vegetable garden and disinfection building, one might see here a certain covering up of traces. Christian opponents of Hitler were incarcerated in Dachau, and Christian forms of remembrance were needed by a considerable number of Dachau’s former inmates. In providing spiritual support, the Protestant and Catholic Churches could make some amends for the degree to which, as institutions, they had tolerated and even collaborated with National Socialism. But there was, equally, a danger that their role in administering consolation in the present would obscure their failures in the past. Moreover, the focus on Christ’s prefigurative agonies invited visitors to the memorial site to view the sufferings of Dachau’s inmates as derived and secondary, or as part of mankind’s condition. Unveiled in September 1968, the International Memorial by Nandor Glid portrays emaciated figures whose thin bodies are so contorted and drawn out that they have become indistinguishable from barbed wire [Plate 1.2]; there are echoes of Christ’s suffering on the cross. Setting camp suffering within a Christian context lends it an air of inevitability and stresses that it can be overcome through divine love and grace. The focus on the consolations of the life after death also usefully deflects attention from issues of immediate human responsibility and redress on earth. As they walk from the top of the memorial site, which houses the exhibition, to the bottom, where the Christian buildings predominate, visitors take part in a ritual of salvation. The journey symbolizes the transition from earth to heaven, or even hell to heaven.

Plate 1.2 The International Memorial at Dachau Memorial Site.

In the former Flossenbürg camp, the Chapel of Atonement ‘Jesus in Prison’ was opened on 25 May 1947. It was constructed from granite stones taken from torn-down camp watchtowers. The Chapel was built at the instigation of former prisoners, notably Poles, but can nevertheless be read as an image of Catholic Bavaria’s ingestion and reprocessing of the past; the vigilant eye of National Socialist guards is replaced by the merciful eye of Christ. Three original watch-towers do remain, one of which is connected to the Chapel by a walkway; but this link implies that the Chapel can transform perpetration into grace and forgiveness. As in the case of Dachau, it seemed that the state of Bavaria preferred to delegate coming to terms with the past to the Christian Church. While it was necessary to lay out graveyards, this could, moreover, serve a dubious purpose, in that the National Socialist past could then be buried along with the bodies. In 1957, 4,387 people who died during death-marches from Flossenbürg were exhumed from provisional graves. They were then reburied in what became the ‘Honorary Cemetery’ with a ‘Park of the Last Place of Rest’ ...