![]()

This book addresses the meanings that have become attached to print mediums in the industrial West since 1800. Even in the digital era, the styles and appearance of letterpress, lithography or silk screen continue to resonate in the graphic design languages we come up against in public space and in our private encounters with the page. We still engage with print culture by thinking about print, using print and producing printed artefacts. Looking at print as a designed object or ‘marked surface’, the approach taken in this book, is a good way of getting into the thick social and cultural contexts that have created current attitudes, and it also challenges the common assumption that we are now bombarded by texts and images that have somehow become dematerialised by new media developments. In fact, it is quite the opposite; digital equipment at home and in the office invites us to compose and print out more new documents on a daily basis. In considering print as a made object, the book will contextualise and integrate narratives of production and reception at a time when both these roles are becoming available to non-specialist writers and authors.

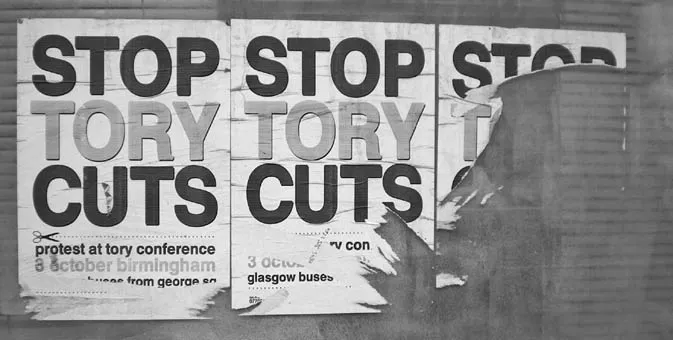

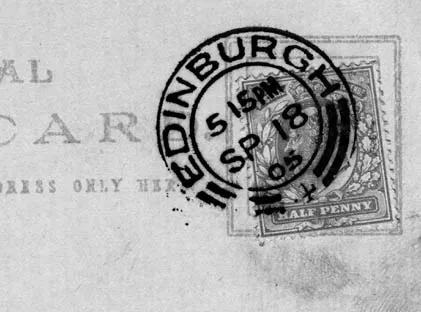

The poster in Figure 1.1 is a home-printed agitational gesture; ‘print’ in this book is not limited to a discrete specialist area, but will be considered in relation to many social and material transactions. Although print culture is often celebrated as a medium of information transfer, promoting knowledge, print is also about litter, bus tickets and propaganda. In fact, before knowledge exchange, print functions more to record how we work to establish trust amongst strangers. We see this when we use and print banknotes, cheques and receipts as material tokens that underwrite a social agreement. Postal services replicate similar print transactions in miniature, for example in Figure 1.2 where the residues of many separate lives in 1905 were suddenly brought together and fixed through print at a quarter past five one September afternoon. This book aims to bring to account such overlooked elements of print in culture, while also considering various incarnations of print culture as broader and deliberative discourses about print. Everyday and localised examples of printing from the past two centuries are open to almost every researcher, wherever they may be based, and are useful for testing their research against broader narratives of print culture. Local examples can suggest that apparently universal statements about the workings of print culture actually come from particular circumstances. For example, Western academics writing for peer-reviewed publications are more ready to characterise printed matter as the vehicle of reliable and lasting information, while the samizdat readers we meet in Chapter 6 would bristle with suspicion when confronted with similar texts. In giving an open acknowledgement of the fact that this book reflects the circumstances of its writing, the book seeks to recognise the contradictions and tensions of trying to describe a medium that is at the same time collective, individual and contested. Singular examples of print open up connections to the material and social circumstances of production. The business of print is populated with competing groups of publishers, print entrepreneurs and workers, all primed to forge and disseminate information. Different groups might construct and nurture their own version of print history for decades until forced into confrontation, as we see in the bloody strikes in Wapping associated with the move from hot metal to digital newspaper production in the 1980s. Self-conscious celebrations of print and its benefits have surfaced at various times, from Victorian promoters of progress to the media-conscious 1960s (when the term ‘print culture’ first came into circulation), and again more mournfully in the 1990s. Just as print culture was often linked with the rise of modern industrial society, so the alleged demise of print under the onslaught of new media is often correlated with the demise of modernity. This book charts the constellation of elements involved in such claims – print, culture, technology, history – through a method that examines the iconography of materials, marks and processes of print. We see how the notion of print culture, first promoted in the work of scholars such as Marshall McLuhan (1962; 2001 [1964]) and Elizabeth Eisenstein (1979; 1983), was connected with the particular cultural moment and the anxieties of these authors who were writing in a period when the expansion of new electronic communications after World War II appeared to threaten older media, and made the qualities of established printed communication more apparent, rather than just as the stuff of everyday life. Now, with the advent of more recent digital communication technologies since the 1990s, the end of print culture once again appears to be inevitable (Birkerts 1994; Finkelstein and McCleery 2005: 26; Gomez 2008). In considering print as a made object, this book in one sense acknowledges McLuhan’s characterisation of print culture – that the medium, as much as the message, is the bearer of meaning – but beyond this it will also question the term by arguing that print culture can only makes sense in the plural, as a diversity of differing practices.

Figure 1.1 | Digital desktop printsa, flyposted to vacant shop window, author photograph. |

Figure 1.2 | Printed postcard, 1905, steel-engraved halfpenny stamp, overstamped with cancellation mark showing time and place of posting, author collection. |

In summing up and saying what now seems to be a premature farewell to the ‘Gutenberg galaxy’ in the 1960s, McLuhan took a distinctive approach. He stressed the importance of the medium of communication, rather than content, in shaping human perception and knowledge. In a similar vein, other scholars of this period such as Elizabeth Eisenstein and William Ivins celebrated the cultural and intellectual benefits of print. Noting that printing can reproduce and spread identical copies of words and images to places far apart in space or time, texts such as Prints and visual communication (Ivins 1992 [1953]) claimed that the invention of printing encouraged scholars to argue about the accuracy of texts, interpretations and data, and hastened the scientific and technological ascendancy of natural philosophers in the West. But descriptions of the workings of print culture in this period often transplanted contemporary values back in time in an anachronistic way. In The printing press as an agent of change (1979) and The printing revolution in early modern Europe (1983) Eisenstein conjured a ‘communications revolution’ during the Renaissance, to which she applied contemporary concepts such as ‘data collection’, ‘storage and retrieval systems’ or ‘communications networks’, suggesting strongly that the development of contemporary secular and industrial society was the result of new kinds of consciousness fostered by the invention of printing. Such ideas are still influential, but they have attracted strong criticism, for example, that the notion of ‘print culture’ is a form of reification (Maynard 1997), that it is a misleadingly over-simplified generalisation (Johns 1998; Dane 2003), or that the term proclaims a naïve technological determinism (Nye 2006). Nevertheless, the term ‘print culture’ is still used and with increasing frequency in many new contexts of study. The term is often used to indicate specific networks of writers, readers and publishers, for example those involved in the expression of radical politics in the nineteenth century (Wood 1994; Gilmartin 1996; Haywood 2004), or in the formation of scientific communities (Latour 1987). Print culture also implies a level of reflexivity – a self-conscious proclamation that print is part of a group’s identity. For example when Eisenstein cited Francis Bacon’s description of printing (in the Novum organum of 1620) as one of three world-changing modern inventions (along with gunpowder and the compass) she implied that the print culture of her existing community of scholars in humanities was also part of a long tradition of print commentary (Eisenstein 1983: 12). William McGregor, an art historian, has argued equally that print was so ubiquitous a medium for visual education that even by the seventeenth century it had become the commonplace guiding metaphor for the workings of the mind and perception, as evidenced in the development of words such as ‘imprint’ or ‘impress’ to denote states of mind (MacGregor 1999: 389–421).

Beginning in nineteenth century, this book gives examples of the ways in which different print mediums and visual languages have accumulated meaning in contemporary visual culture and graphic design and in the study of humanities. Each chapter addresses different kinds of print medium, but in addition the book also follows a chronological progression through to the present. So, for example, Chapter 3 on letterpress printing is connected to cultural and historical debates associated with the mid-nineteenth century, while offset lithography is discussed in relation to mid-twentieth century developments in Chapter 6. The book does not present a comprehensive history of the notion of print culture, but asks how cultural history and theory might mesh with specific print cultures. For example, lithography – a protean medium that gave rise to fears of unbridled piracy in the early nineteenth century – will be explored in relation to the development of ideas of grades of authenticity in the reading of images. The nineteenth century is a good place to start for several reasons, in part because, as we will see, many current assumptions and myths about the nature of print were formulated during this time. With this in mind, it is not surprising that writers such as Elizabeth Eisenstein have described this period as the ‘zenith of print culture’ (Eisenstein 2011: 153–97), or that Ivins now appears to be less of a twentieth-century modernist and more a born-again Victorian. Print gained huge cultural significance as a metaphor for industrial production in general during the first half of the nineteenth century, always tinctured with the ink, oil and metal of the presses and their machine actions. The development of mechanised paper production and the invention of steam printing machinery supported a rapid expansion of the printing and publishing industries. For readers, prices fell; levels of literacy increased and many kinds of texts both factual and fictional were produced (Altick 1957; Eliot 1995: 19; Finkelstein and McCleery 2005: 113–15). Although by definition print is a medium for producing multiples, the expansion of the market through industrial means of production also meant significant fragmentation and conflict at this time. Mass markets are made up of competing groups, all vying for status. In considering the different audiences addressed by different techniques, we can see the limitations of those seductive phrases ‘print culture’ and ‘mass market’ when they are used without qualification.

Print culture is fermented in many different academic disciplines, but also in daily life and in workplaces. Academic research into book history is one notable stronghold of print culture, in both senses, as this is a community caught up in print technologies that is also constantly engaged in self-reflexive and critical debate about its own assumptions and methods. In addition to a large and expanding body of research and literature from individual scholars, book history is also promoted through various national and international initiatives, such as the Centre for the History of the Book at the University of Edinburgh, the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing (SHARP), or the Program in the History of the Book in American Culture that set in motion the five volume collaborative project of A history of the book in America (2007–10). Book history is a fairly recent field of study, emerging from older disciplines such as bibliography, literary studies, and social or economic history. Because books come together through a totality of different activities book history favours a synthetic approach. For example, literary criticism alone could not address the task of examining the conditions of production, or why printers or designers have chosen certain styles of typography and layout in different editions. Equally, while bibliographers used to concentrate on the physical materiality of books and their internal evidence, for example, by comparing and contrasting the evidence of wear on metal types and printing plates in order to ascertain when and where a certain volume was produced, these observations began to feel thin without some explanation of the social field in which the book was produced, disseminated and read. With these newer sociological approaches printers, readers, publishers and distributors have all come to be considered as the makers of texts. French scholars such as Chartier, Febvre and Martin (1997 [1976]) influenced English speaking historians, for example Robert Darnton with his concept of the ‘communication circuit’ or D.F. McKenzie’s expansion of the ‘sociology of texts’ (Finkelstein and McCleery 2002; 2005; Howsam 2006). The ‘sociology of texts’ approach embraces many groups of people beyond the world of books and scholars, showing many more diverse fields of production and use, the ‘full range of social realities which the medium of print had to serve, from receipt blanks to bibles’ (McKenzie 1986: 6). Looking at the social and cultural construction of texts in this way has pricked critical awareness about the very notion of print culture itself. Writers such as David McKitterick or Adrian Johns attacked earlier claims in the work of Eisenstein or Ivins that printing produced identical texts, or ‘exactly repeatable visual statements’. Whereas Elizabeth Eisenstein argued that standardisation, dissemination and ‘fixity of texts’ created a reliable resource for scholars in the early modern period, Johns disputed this claim. Instead, many texts were regarded with suspicion due to piracy or malicious parody, for as the enemies of print argued; what could be worse than multiplying a dangerous lie? Even with the best and most scholarly intentions, many printed texts were simply not the same even within one edition (Johns 1998: 28–33; McKitterick 2003: 151–64). Trust in print and in ‘fixity’ was a later development, and came about through the machinations of people, not because there is some inherent quality in print as a medium.

The idea that print is a medium of and for social formation is the starting point in many histories of media and communications, in cultural theories of media, and in the very broad field of ‘visual studies’ (Elkins 2003; Barnhurst, Vari and Rodriguez 2004). Cultural theory in part derived from the critical projects of writers and thinkers associated with the ‘Frankfurt school’ from the 1920s onwards, who sought to examine society and the formation of cultural assumptions in order to prompt a questioning attitude in the reader and hasten public action for change. Mass media, and the role of representations in the formation of individual consciousness and social hierarchies, was an important focus of study for these theorists such as Walter Benjamin, Theodor Adorno and Jurgen Habermas. Habermas, for example developed an account of the so-called ‘public sphere’, created through late eighteenth-century print forms of newspapers and novels. The ‘public sphere’ is now a term that has been applied to many contexts, but originally denoted an imaginary realm in bourgeois market-oriented culture where educated free citizens engaged in rational debate about public and social policy (Habermas 1989 [1960]; Briggs and Burke 2009: 79–90). In a similar style, print has been described as the medium that developed ‘imagined communities’ (Burke 2004: 62–64). In Europe, vernacular languages such as modern French, German or English eventually displaced Latin as the language of officialdom through prestigious projects such as translating and printing the Bible, for example in the English Authorized Version of 1611 (Briggs and Burke 2009: 29). Separate vernacular languages that were regimented and stabilised by print then began to form the imagined communities of nations and ethnic groups (Finkelstein and McCleery 2005: 18–19; Anderson 2006 [1983]).

Historians of science are now also important contributors to the study of print culture. In the late twentieth century science and technology studies adopted cultural and sociological approaches in order to understand the construction of systems of knowledge and practice through publications such as The social construction of technological systems (Bijker, Hughes and Pinch 1987). For example in the period since the foundation of the Royal Society in Britain in 1660s, men of science worked to establish trust in their knowledge through establishing belief in their printed communications. In an influential text, Leviathan and the air pump, Shapin and Schaffer examined how trust in print was built up. Men of science used ‘three technologies’ (that is, material, literary and social technologies) to recruit supporters and gain allies for the new methods and theories of empirical science (Shapin and Schaffer 1985: 18–25). In The nature of the book: print and knowledge in the making Adrian Johns continued this theme of the interlocking relationship of print and the history of scientific practices through further case studies that demonstrate how knowledge was made and defended in the context of warring research allegiances through to the late eighteenth century (Johns 1998: 6). In Victorian sensation, James Secord (2000) synthesised approaches from printing and publishing history, history of reading and history of science in a detailed and exciting account of the making and reception of the publishing outrage of the 1840s, the anonymous Vestiges of the natural history of creation, a work that carried ideas of natural science and evolution into the cultural context of nineteenth-century Britain. In histories of technology and industry, less critical attention has been given to the print culture of manufacturing until fairly recently, even though, as this book will demonstrate, the prophets and promoters of the ‘machine dreams’ of industrialisation (Sussman 2000) in the nineteenth century used printing as an extended metonym for the virtues of the entire factory system. Recently, however, in The arts of industry in the age of enlightenment (2009) Celina Fox developed an account of the formation of technical styles of representation by asking how skills in the ‘useful arts’ in Britain were built up and communicated in the period before 1850. She considered the practices of drawing, model-making, and the convivial technologies of clubs and societies, alongside prints and print communications such as encyclopaedias and self-help magazines (Fox 2009: 8, 251–87), following from the work of earlier Victorianists and social historians such as Klingender (1972) or Briggs (1979).

Evidently, print is a medium of images as well as texts, and the study of visual print culture extends into art history and cultural history – from worlds of fine art connoisseurship to folk art and ephemeral satire, or to the workings of the print trade (Lambert 1987; Anderson 1991; Ivins 1992 [1953]; Griffiths 1996; Hallett 1999; Briggs and Burke 2009: 45–50). Print culture, as a business of design and graphic communication, is also part of design history (Margolin 1988; Drucker 2009) and architectural history (Carpo 2001), just as the study of visual representations and their circulation in print is now also a key aspect of the history of science. There is also a vast literature on print culture from graphic designers and working practitioners of all kinds. Many publications are examples of enthusiastic ‘trade’ literature, documenting for example the triumphs of an advertising campaign; works like these are excellent resources for research. More recently, however, design professionals have developed more distanced and critical registers of analysis directed at their own history and practices, particularly from those who are also involved in teaching or academic research. One constant theme amongst concerned professional designers since at least the 1960s has been to draw attention to the power of their own specialism, either when used to dominate the civic realm or, in the service of advertising, to persuade, dazzle and indoctrinate. Ken Garland’s witty manifesto First things first of 1964 for example lamented a system that applauded designers and new students for applying their skill and imagination to sell such things as: ‘cat food, stomach powders, detergent, hair restorer, striped toothpaste, aftershave lotion, beforeshave lotion, slimming diets, fattening diets, deodorants, fizzy water, roll-ons, pull-ons, and slip-ons’, rather than in more worthy outlets and lasting expressions such as ‘street signs, books and periodicals, catalogues, instructional manuals, industrial photography, educational aids, films, television features’ (Garland 1999: 154–59). Although such ‘reformist’ positions appear at first glance critical, nevertheless they still serve to bolster the power of the professional designer in society. In the second half of the twentieth century the development of university departments of graphic design has prompted a further expansion of academic and critical writing amongst teachers and researchers who are also professional designers (Margolin 1988; Bierut et al. 1994; 1999; Heller and Ballance 2001; Lavin 2001: 121–23). Although this book is indebted to this extensive literature, it will not present a guide or history of typography and graphic design practice as this area is very well served by many design professionals and practitioners who bring deep expertise and knowledge to their publications, from specialist guides to student introductory texts on graphic design languages, history, typography and other aspects of visual communication (Heller and Pomeroy 1997; Meggs 1998; Baines and Haslam 2005). Instead this book recognises this powerful group of practitioners as one element in contempo...