- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Performance Theory

About this book

Few have had quite as much impact in both the academy and in the world of theatre production as Richard Schechner. For more than four decades his work has challenged conventional definitions of theatre, ritual and performance. When this seminal collection first appeared, Schechner's approach was not only novel, it was revolutionary: drama is not just something that occurs on stage, but something that happens in everyday life, full of meaning, and on many different levels. Within these pages he examines the connections between Western and non-Western cultures, theatre and dance, anthropology, ritual, performance in everyday life, rites of passage, play, psychotherapy and shamanism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

APPROACHES

THE CAMBRIDGE ANTHROPOLOGISTS

For the last hundred years or more, Greek tragedy has been understood as an outgrowth of rites celebrated annually at the Festival of Dionysus. Those rites have been investigated both in their relation to the god Dionysus and in their relation to the primitive religion of the Greeks. The result is a conception of Greek tragedy which is very different from that which prevailed from the Renaissance into the eighteenth century. The Renaissance humanists and their successors saw it in “civilized” and rational terms; in our time we see that much of its form and meaning is due to its primitive source, and to the religious Festival of which it was a part. This new conception of Greek tragedy has had a very wide effect upon our understanding of the sources of poetry in our tradition, and also upon modern poetry itself, including theater and music. . . .

Unfortunately little is known directly about the rites of the Dionysian Festival, or about the poets, Aeschylus’ predecessors, who gradually made the tragic form out of ritual. The scholars who devote their lives to such matters do not agree upon the evidence to be accepted, nor upon the interpretation of the evidence. But some of their theories are extremely suggestive, especially those of the Cambridge school, Frazer (of The Golden Bough), Cornford, Harrison, Murray, and their colleagues and followers. It is this school which has had the deepest influence upon modern poetry and upon the whole climate of ideas in which we now read Greek tragedy. . . .

The theory expounded by Murray has been much criticized by other experts, and the whole field is full of disputes so erudite that the non-specialist can only look on in respectful silence.

(F. Fergusson, in Aristotle 1961: 36–9)

It’s time to break the silence.1 The instrumental books Fergusson alludes to are Jane Ellen Harrison’s Themis2 (1912), Gilbert Murray’s The Four Stages of Greek Religion (1912a – later Five Stages, 1925), and Francis Cornford’s The Origin of Attic Comedy (1914). Cornford’s book is the only one entirely devoted to the theater, and thus it has been extremely popular among theater people. But the ideas espoused by the other books are just as well known. The Cambridge thesis purports to explain not only the origins of Greek tragedy and comedy, but their “essential natures” as well. Second- and third-generation critics have extended the somewhat modest proposals of the Cambridge group into “universal” systems widely used to explain the “basic form of theater” not only in the west but everywhere. Fergusson’s The Idea of a Theater (1949) is a most distinguished American example. Fergusson applies the Cambridge thesis to a wide range of authors, from Sophocles to T. S. Eliot, Shaw, and Pirandello. His essays on Oedipus and Hamlet are classics. But these essays would be just as interesting, and a good deal less cluttered, if he did not insist on a ritual beneath the theatrical action of the plays.

The Cambridge thesis is not difficult. Studying survivials of Greek ritual, these scholars found what they thought to be traces of a “Primal Ritual” from which they felt both Attic tragedy and the surviving rituals derived. Murray began his “Excursus”:

The following note presupposes certain general views about the origin and essential nature of Greek Tragedy. It assumes that Tragedy is in origin a Ritual Dance, a Sacer Ludus. . . . Further, it assumes, in accord with the overwhelming weight of ancient tradition, that the Dance in question is originally or centrally that of Dionysus, performed at his feast, in his theater. . . . It regards Dionysus in this connection as an “Eniautos-Daimon,” or vegetation god, like Adonis, Osiris, etc., who represents the cyclic death and rebirth of the earth and the world, i.e., for practical purposes, of the tribe’s own lands and the tribe itself. It seems clear, further, that Comedy and Tragedy represent different stages in the life of this Year Spirit.

(Murray 1912b: 341)

The rub is: the assumptions of the Cambridge group have never been proven. A tremendous amount of archeological digging has gone on in Greece over the past seventy-five years, but nothing has turned up expressing all the elements of either drama or the Primal Ritual.3 This is crucial because Murray asserts, “If we examine the kind of myth which seems to underlie the various ‘Eniautos’ [death-rebirth] celebrations we shall find an Agon . . . a Pathos . . . a Messenger . . . a Threnos or lamentation . . . an Anagnorisis – discovery or recognition . . . [and a] Theophany” (1912b: 343–4). This formal sequence, propagators of the Cambridge thesis say, is the core action of the Primal Ritual, surviving fragments of the dithyramb, and Greek tragedy. Cornford’s contribution was to do for comedy and phallic dances what others did for tragedy and dithyramb. His reasoning is identical. “Athenian Comedy arose out of a ritual drama essentially the same in shape as that from which Professor Murray derives Athenian Tragedy” (Cornford 1914: 190). Harrison, in Ancient Art and Ritual, gleefully makes the connections:

We shall find to our joy that this obscure-sounding Dithyramb, though before Aristotle’s time it has taken literary form, was in origin a festival closely akin to those we have just been discussing [seasonal deathrebirth celebrations]. The Dithyramb was, to begin with, a spring ritual; and when Aristotle tells us tragedy arose out of the Dithyramb, he gives us, though perhaps half unconsciously, a clear instance of a splendid art that arose from the simplest of rites; he plants our theory of the connection of art with ritual firmly with its feet on historical ground.

(Harrison 1913: 76)

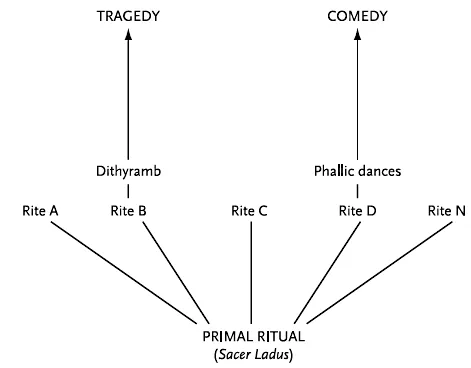

Before discussing how firmly Aristotle had his feet on the ground, let me depict the Cambridge thesis (figure 1.1). The Primal Ritual (Murray calls it a Sacer Ludus) gave rise to a number of rites. One of these developed into the dithyramb from which Greek tragedy arose; another became the phallic dances from which comedy evolved. The argument applies turn-of-the-century anthropological theories of cultural evolution and diffusion. It is highly speculative with several missing links.

Figure 1.1

The clearest example of the Primal Ritual’s form comes from one of the last Greek tragedies to be written, Euripides’ The Bacchae where, from line 787 to the end, Murray finds the “whole sequence” of his Sacer Ludus. To do this, however, he must assume that “Pentheus is only another form of Dionysus himself”4 – thereby “explaining” why it is the young king, and not the god, who is torn to pieces. Nor is there any resurrection or apotheosis of Pentheus. It is Dionysus who appears, not to signal, as Murray says, an “extreme change of feeling from grief to joy,” but to curse the whole city of Thebes. Using The Bacchae at all makes Murray’s argument smell of tautology. But the Cambridge group must use The Bacchae, because other links with the Primal Ritual are even weaker. There is no Primal Ritual yet discovered;5 the connections between what rituals can be shown to have existed and the dithyramb are doubtful; and the connections between the dithyramb and Greek theater are unprovable.6

Theories of cultural evolution have long been challenged by anthropologists. The methodology of J. G. Frazer, which the Cambridge group freely uses, has been almost entirely discredited. Yet Murray maintained as late as 1961 (in his Foreword to Theodor H. Gaster’s Thespis) that “It is hardly an exaggeration to say that when we look back to the beginnings of European literature we find everywhere drama, and always drama derived from a religious ritual designed to ensure the rebirth of a dead world” (Murray 1961: 9). However true this may be about the emergence of Christian theater from medieval church ritual, it is not true of either Greek theater or European theater (and its derivatives) from the Renaissance to the present. We might even see the reverse process: a dynamic braiding of ritual and entertainment (see chapter 4).

The connection between Greek drama and the dithyramb depends largely upon Aristotle’s comments in chapter 4 of Aristotle’s Poetics (Butcher’s translation, 1961):

Tragedy – as also Comedy – was at first mere improvisation. The one originated with the authors of the Dithyramb, the other with those of the phallic songs, which are still used in many of our cities.

Even Cornford doubted Aristotle’s authority as an ethnologist:

How much he [Aristotle] knew or might have inferred about the earliest stages of Comedy we cannot tell. He may have known as little as Boileau knew of the beginnings of the modern French Theatre. . . . If Boileau could be so ignorant of two centuries of ecclesiastical drama, of which tens of thousands of lines were in existence, we need not wonder if Aristotle did not know that the plays of Chionides and Magnes retained traces of a broken-down ritual plot, and that yet fainter traces survived in Aristophanes.

(Cornford 1914: 219)

Pickard-Cambridge is equally clear, but to prove the opposite point:

as regards comedy, it is very doubtful whether he [Aristotle] is strictly correct; as regards tragedy, the difficulties of his view will shortly become plain. We have, in short, to admit that it is impossible to accept his authority without question, and that he was probably using that liberty of theorizing which those modern scholars who ask us to accept him as infallible have certainly not abandoned.

(Pickard-Cambridge 1962: 95)

T. B. L. Webster finds that Aristotle makes “two completely distinct points: 1) tragedy was an offshoot from the Dithyramb; 2) (six lines later) it changed from satyric and was solemnized late; and there is not justification for equating them” (in Pickard-Cambridge 1962: 96). Murray deals with this slippery transformation thus:

It would suit my general purpose . . . to suppose that the Dionysus-ritual had developed into two divergent forms, the satyr-play of Pratinas and the tragedy of Thespis, which were at a certain date artificially combined by a law.

(Murray 1912b: 344)

This rescues the Cambridge thesis, but it is all speculation. The fact is we cannot depend on Aristotle; nor can we accept what he says and arrive at the Cambridge thesis.

Why then has the Cambridge idea held such sway? It can be compressed, codified, and generalized: it is teachable. It is self-repairing: where the Primal Ritual cannot be found it has simply “evolved out of recognition”; where only “fragments” exist, these are vestiges, and so forth. It seems to explain everything: origins, form, audience involvement, catharsis, and dramatic action – especially the conflicts, mutilations, and deaths that characterize Greek tragedies. In short, the thesis is elegant, brilliant, speculative criticism. But it is no more than that. The “scientific proofs” the Cambridge group sought for their ideas have not been found. And perhaps it is time to abandon the Cambridge thesis as one which is too limiting, that no longer suits current perceptions of theater.

Ritual as the Cambridge group understands it does not seem very closely related to Greek theater – or Elizabethan or modern.7 The meaning of the word must be distorted out of usefulness if it is to apply equally to Seven Against Thebes, Philoctetes, The Bacchae, Lear, Mother Courage, Waiting for Godot, The Bald Soprano, The Tooth of Crime – or any other random group of distinguished plays. Even if one restricts the selection to a single period, the difficulties are immense. To apply the Cambridge thesis is to force the plays into contexts other than their own, to read around and under them. The development of happenings, intermedia, performance art, and so on raises still further questions. As for medieval theater which had as one of its sources church ritual,8 the players kept the biblical characters and plots while soon abandoning the form of the Mass and embroidering the stories with secular incidents.

I am not going to replace the Cambridge origin theory with my own. Origin theories are irrelevant to understanding theater. Nor do I want to exclude ritual from the study of the performative genres. Ritual is one of several activities related to theater. The others are play, games, sports, dance, and music.9 The relation among these I will explore is not vertical or originary – from any one to any other(s) – but horizontal: what each autonomous genre shares with the others; methods of analysis that can be used intergenerically. Together these seven comprise the public performance activities of humans.10 If one argues that theater is “later” or more “sophisticated” or “higher” on some evolutionary ladder and therefore must derive from one of the others, I reply that this makes sense only if we take fifth century BCE Greek theater (and its counterparts in other cultures) as the only legitimate theater. Anthropologists, with good reason, argue otherwise, suggesting that theater – understood as the enactment of stories by players – exists in every known culture at all times, as do the other genres.11 These activities are primeval, there is no reason to hunt for “origins” or “derivations.” There are only variations in form, the intermixing among genres, and these show no long-term evolution from “primitive” to “sophisticated” or “modern.”12 Sometimes rituals, games, sports, and the aesthetic genres (theater, dance, music) are merged so that it is impossible to call the activity by any one limiting name. That English usage urges us to do so anyway is an ethnocentric bias, not an argument.

PLAY, GAMES, SPORTS, THEATER, AND RITUAL

Several basic qualities are shared by these activities: 1) a special ordering of time; 2) a special value attached to objects; 3) non-productivity in terms of goods; 4) rules. Often special places – non-ordinary places – are set aside or constructed to perform these activities in.

Time

Clock time is a mono-directional, linear-yet-cyclical uniform measurement adapted from day–night and seasonal rhythms. In the performance activities, however, time is adapted to the event, and is therefore susceptible to numerous variations and creative distortions. The major varieties of performance time are:

- Event time, when the activity itself has a set sequence and all the steps of that sequence must be completed no matter how long (or short) the elapsed clock time.

Examples: baseball, racing, hopscotch; rituals where a “response” or a “state” is sought, such as rain dances, shamanic cures, revival meetings; scripted theatrical performances taken as a whole. - Set time, where an arbitrary time pattern is imposed on events – they begin and end at certain moments whether or not they have been “completed.” Here there is an agonistic contest between the activity and the clock.

Examples: football, basketball, games structured on “how many” or “how much” can you do in x time. - Symbolic time, when the span of the activity represents another (longer or shorter) span of clock time. Or where time is considered differently, as in Christian notions of “the end of time,” the Aborigine “Dreamtime,” or Zen’s goal of the “ever present.”

Examples: theater, rituals that reactualize events or abolish time, make-believe play and games.

Boxing offers an unusual combination. The length of each round (3 minutes) and the fight (a certain number of rounds) is set time. But a KO can end the fight at any moment and is event time while the measure of a KO (the 10 count) is set time.

In racing, the racers are competing against each other, either directly or indirectly (attempting to set a new record). The clock is the means by which racers are compared to each other. In football, however, the clock is very active in the game itself. Both teams, while playing against each other, are also playing with/against the clock. Time is there to be extended or used up. While stalling is a negligible strategy in baseball and a disastrous one in racing, it is crucial in football, where many games end...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the Routledge Classics Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- Introduction: The Fan and the Web

- 1: Approaches

- 2: Actuals

- 3: Drama, Script, Theater, and Performance

- 4: From Ritual to Theater and Back: The Efficacy–Entertainment Braid

- 5: Toward a Poetics of Performance

- 6: Selective Inattention

- 7: Ethology and Theater

- 8: Magnitudes of Performance

- 9: Rasaesthetics

- References

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Performance Theory by Richard Schechner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.