![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

This book considers Development Coordination Disorders (DCD) in the context of other specific learning difficulties. It also considers how the child or adult is recognised and managed in school or in the workplace, and the implications of the diagnosis or ‘the label’ being given.

It does not give all of the answers to the problems but rather allows the reader to consider the underlying difficulties, understand the deficits, critically analyse current research and practice and then consider the solutions. It is intended to invite thought and promote discussion rather than being an easy ‘reach for the shelf for the answers’ book.

Why diagnose/why label in the first place?

This is really dependent upon who gives the label and who wants to have a label.

A label can mean:

- Acknowledgement for the parent of worries and concerns, and confirmation of the condition: allows others to see the parent as not just ‘another over-anx-ious parent’.

- The provision of funds or services for the child.

- The provision of a cohort of individuals with signs and symptoms that may be useful for research.

- Allowing individuals working with the child to read up around the condition and consider what type of support is required.

- It may be used in legal cases as a reference point to consider one child’s support compared to others.

- It may be used to plan service delivery or for baseline assessment and in-school remediation programmes.

- It may suggest negative connotations and may mean that individuals who come into contact with the child have preconceived ideas about the strengths and difficulties based on their experience of others with the same label they have come into contact with, who could even have been atypical.

- Placing children in very small boxes and not seeing them from all perspectives – this may lead to missing a diagnosis.

- The child perhaps ends up with many labels but not the right type of help.

- The child then being ‘tattooed’ for life with what they can’t do rather than what they can do.

- One label does not carry as much weight as another; for instance, medical labels may seem more important than educational ones (e.g. epilepsy versus dyslexia).

Should we give diagnostic or functional labels?

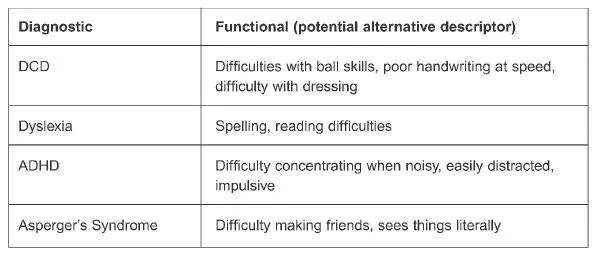

So should we be giving diagnostic or functional labels to help individuals with DCD and other specific learning difficulties? Figure 1.1 contrasts diagnostic and functional labels.

Figure 1.1 Diagnostic and functional labels

What conditions fall under the label of specific learning difficulties?

Specific learning difficulties include conditions such as:

- Dyslexia

- Asperger’s Syndrome

- DCD (Developmental Coordination Disorder)

- ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder)

- DAMP (Deficit of Attention and Motor Perception)

- Dysgraphia

- Dyscalculia

Co-morbidity

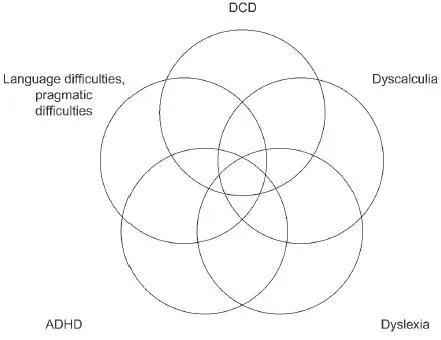

Thought needs to be given to the extent to which there is co-morbidity or whether the above conditions overlap (see Figure 1.2).

‘Co-morbidity is the rule rather than the exception’ (Kaplan et al. 1998) – specific learning difficulties do commonly overlap with one another. Are all conditions coming from some similar root causes, all having atypical brain functioning? It is where and how in the brain the pattern of difficulties arises that leads the individual to have a range of problems which we then label accordingly.

Co-morbidity is described as a situation where two or more conditions that are diagnostically distinguishable from one another tend to occur together. The exact nature of the relationship between co-morbid conditions is a matter of some debate in the research literature (Martini et al. 1999). Henderson and Barnett (1998) also reviewed the labels issue and discussed the issues of classification. Gillberg in 1998 (in Landgren et al. 1998) looked at the overlapping nature of DCD and ADHD and the prevalence of the coexisting conditions in a population study in Sweden. In the study of all 6–7-year-old children in a Swedish community (approximately 25,000 inhabitants), 589 6–7-year-old children from the town of Mariestad were identified. Of these children, 10.7 per cent were noted to have some kind of neurodevelopmental disorder. This was broken down into the following groups: DAMP 5.3 per cent, ADHD 2.4 per cent, DCD 1.7 per cent and mental retardation (IQ less than 70) 2.5 per cent. The estimated rates were: DAMP 6.9 per cent, DCD 6.4 per cent and ADHD 4.0 per cent. All children with

Figure 1.2 Co-morbidity/overlap

DAMP had DCD and attention deficits, and about half of them fulfilled the criteria for ADHD.

Another population study (Kaplan et al. 1998) also found overlap with children who had DCD, ADHD and dyslexia. Of this diagnosed group, 23 per cent were found with ADHD, DCD and dyslexia. Only 10 per cent had ADHD and DCD, and 22 per cent had dyslexia and DCD only.

It is particularly difficult to determine whether one condition is in fact a symptom of the other – causality versus correlation. These important debates aside, research provides support for a number of conditions co-occurring with learning disabilities more often than expected ‘just by chance’.

The largest body of studies supports a co-morbid relationship between learning difficulties (usually termed learning disabilities in the US) and attention deficit disorder (with or without hyperactivity). This extensive research, featuring comorbidity estimates as high as 70 per cent, was summarised recently by Riccio et al. (1994).

A large percentage of those who have ADHD also have accompanying learning difficulties, while approximately 30 per cent of those who have learning difficulties also have ADHD.

A group of disorders also found frequently to be co-morbid with learning difficulties is that involving social, emotional, and/or behavioural difficulties. Studies suggest that anywhere from 24 to 52 per cent of students with learning difficulties have some form of such a disorder (Rock et al. 1997). This group encompasses diagnoses such as conduct disorder and oppositional/defiant disorder (Shaywitz and Shaywitz 1991). Research also suggests that depressive or dysthymic disorders co-occur with learning difficulties (San Miguel et al. 1996) although the nature of the relationship continues to be controversial and requires further research. This is discussed more fully later in the book.

A recent report in the British Medical Journal (June 2002) showed that in the US 7 per cent of the childhood population has ADHD, with half supposed to have an associated ‘other learning disability’. There is difficulty comparing figures because different terminology is used in different countries and so there is a lack of consistency in what specialists are measuring.

Research provides significant evidence supporting the co-morbidity of ADHD with the following disorders: Tourette’s Syndrome, schizophrenia, epilepsy, language/communication disorders (Riccio et al. 1994) and Developmental Coordination Disorder (Martini et al. 1999, Missiuna and Polatajko 1995).

What is the evidence for co-morbidity in DCD?

The difficulty of counting ‘clean’ populations that do not have a mixed profile has been discussed time and again by researchers. Other research work completed by Martini et al. (1999), Henderson and Barnett (1998), and Clarkin and Kendall (1992), has discussed how difficult it is to determine whether one condition is in fact a symptom of another.

The same quandary is seen if you look at material written by the specific learning disability charities such as the BDA, I-CAN, the Dyslexia Institute, and AFASIC, to name a few. You may be confused to see similar symptoms and signs for differing conditions such as ADHD, dyslexia, DCD and Asperger’s Syndrome. It seems that one disorder ‘pinches’ symptoms and signs from another. Is the reason for this that we tend to assess only bits of the child in isolation, and tend not to look at the ‘whole’ child? The label is sometimes determined by which service the child and family access.

It is important to diagnose these underlying difficulties accurately in order to decide how to help remediate and support the child. This then enables and informs the education system how to create and develop an appropriate Individual Education Plan (IEP) for the child. Accurate diagnosis leads to accurate intervention plans tailored to the specific needs of the child and not packaged neatly to fit the label.

How do we define DCD?

DSM-IV Sourcebook American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-IV)

Diagnostic features

The essential features of Developmental Coordination Disorder are:

(Criterion A) A marked impairment in the development of motor coordination.

(Criterion B) The diagnosis is made only if this impairment significantly interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily living.

(Criterion C) The diagnosis is made if the coordination difficulties are not due to a general medical condition (e.g. cerebral palsy, hemiplegia, or muscular dystrophy) and the criteria are not met for Pervasive Developmental Disorder.

(Criterion D) If mental retardation is present, the motor difficulties are in excess of those usually associated with it.

The manifestations of this disorder vary with age and development. For example, younger children may display clumsiness and delays in achieving development motor milestones (e.g. walking, crawling, sitting, tying shoelaces, buttoning shirts, zipping pants). Older children may display difficulti...