eBook - ePub

Reflection

Turning Experience into Learning

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reflection

Turning Experience into Learning

About this book

First Published in 1985. This is a volume of collected articles on reflection in learning, looking at the model, experience-based learning, development of learning skills, writing and the importance of the listener.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Promoting Reflection in Learning: a Model

Introduction

In the Introduction we presented some illustrations of the role of reflection in common learning situations. We are now in a position to present our own model of reflection in learning. We have been led to this by an analysis of examples of the kind discussed above, by our own experience of the processes of learning and the work of a number of authors who have considered reflection as a part of learning.

We wish to restrict our scope to what Tough (1979) terms ‘deliberate’ learning. That is, learning which is intentional in which learners are aware that they are learning; learning with a definite, specific goal rather than generalized learning, for example, to ‘develop the mind’; learning which is undertaken in order to pursue this goal; and learning which the individual intends to retain (Knapper and Cropley, in press). Of course much of our discussion may also apply to other less conscious or less organized forms of learning, but these involve other considerations which would take us away from our main area of interest. Deliberate learning occurs within educational and training institutions, but a great deal takes place on a less formal basis away from these institutions (Tough, 1979). In addition we wish to focus primarily on experiential or experience-based learning (Boud and Pascoe, 1978) rather than what Coleman (1976) refers to as classroom learning which concerns symbolic or information assimilation, although we believe that similar considerations might also apply in these latter areas.

Reflection is a form of response of the learner to experience. In our model we have indicated two main components: the experience and the reflective activity based upon that experience. In the sense in which we are using the term, experience consists of the total response of a person to a situation or event: what he or she thinks, feels, does and concludes at the time and immediately thereafter. The situation or event could be part of a formal course, eg a workshop, a field trip, a lecture; or it could be more informal: an event arising from a personal study project or from the actions of a community group, or a totally unplanned occurrence in daily life. It could be provoked by an external agent or it could be an internal experience, arising out of some discomfort with one's present state. In most cases the initial experience is quite complex and is constituted of a number of particular experiences within it. In the case of the child care student discussed in the Introduction, the learning experience would consist of the time spent within the classroom, but within that there would be many observations, thoughts, perceptions, reactions, awkward moments, and interchanges which would make up the total experience.

After the experience there occurs a processing phase: this is the area of reflection. Reflection is an important human activity in which people recapture their experience, think about it, mull it over and evaluate it. It is this working with experience that is important in learning. The capacity to reflect is developed to different stages in different people and it may be this ability which characterizes those who learn effectively from experience. Why is it that conscious reflection is necessary? Why can it not occur effectively at the unconscious level? It can and does occur, but these unconscious processes do not allow us to make active and aware decisions about our learning. It is only when we bring our ideas to our consciousness that we can evaluate them and begin to make choices about what we will and will not do. For these reasons it is important for the learner to be aware of the role of reflection in learning, and how the processes involved can be facilitated. Some authors (for example, Taylor, 1981) present reflection as a stage in the learning process which occurs after substantial other activity has taken place, towards the latter part of a one-semester course, for instance. While we accept that major periods of reflection may take place in this manner we also wish to include in our definition more modest reflective activities which may occur daily.

In our view, reflection in the context of learning is a generic term for those intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to new understandings and appreciations. It may take place in isolation or in association with others. It can be done well or badly, successfully or unsuccessfully. However, we wish to focus on what learners and teachers can do to ensure that it is a productive experience.

Probably, for adult learners, most events which precipitate reflection arise out of the normal occurrences of one's life. The impetus may arise from a loss of confidence in or disillusionment with one's existing situation. This could be provoked by an external event, or could develop from one's own reflection on a whole series of occurrences over time, causing a dissatisfaction which leads to a reconsideration of them. Boyd and Fales (1983) refer to this experience as an ‘inner discomfort’, and Dewey writes of:

a state of doubt, hesitation, perplexity, mental difficulty, in which [reflective] thinking originates, and ... an act of searching, hunting, inquiring, to find material that will resolve the doubt, settle and dispose of the perplexity. (Dewey, 1933, p12)

Reflection may also be prompted by more positive states, for example, by an experience of successfully completing a task which previously was thought impossible. This may stimulate a reappraisal of other tasks and the planning of new experiences. For someone who has acquired some facility in reflection, the personal affective aspect would be a more frequent impetus rather than particular activities planned by others.

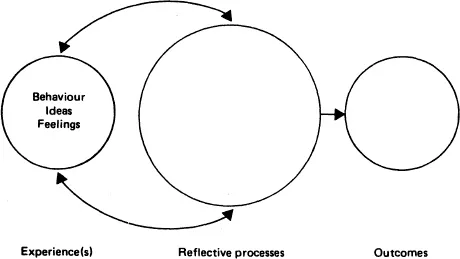

We believe that the more teachers and learners understand this reflective aspect of learning and organize learning activities which are consistent with it, the more effective learning can be. The model points to the starting point and objects of reflection: the totality of experiences of learners, the behaviour in which they have engaged, the ideas of which learners are aware and the feelings which they have experienced. It designates the outcomes of reflection, which may be a personal synthesis, integration and appropriation of knowledge, the validation of personal knowledge, a new affective state, or the decision to engage in some further activity. It also points to the various intellectual and affective processes involved in reflection. These may be facilitated by individual learners or, in some cases, by others assisting them in learning. Figure 1 presents this diagrammatically.

Figure 1 A model of reflection in the learning process

In discussing the model we will for the sake of simplicity refer to the initial learning experience as if it were a singular event; we will also assume in talking about reflection that a particular event has occurred which is the focus of reflection. Of course, in practice we all have a number of experiences over a period of time some of which will become the focus of reflection and some of which will not; often these will not be perceived as separate incidents and it may not be possible for us to identify a particular event which acts as a trigger. However, the general features of reflection in such circumstances are similar. Although we have defined the scope of what we term reflection, and we believe that this corresponds generally to current usage, other authors use different terms for this concept. For example, van Manen (1977) following the German tradition uses the word ‘experience’, and More (1974) uses ‘learning’.

Despite all that has been written about reflection it is difficult to be precise about the nature of the process. It is so integral to every aspect of learning that in some way it touches most of the processes of the mind. As yet little research has been conducted on reflection in learning and that which has been undertaken offers few guidelines for the practical problems which face us as teachers and learners. However, it is possible to extract some principles from those who have examined their own learning processes.

John Dewey wrote a great deal about what he referred to as reflective thought and, in common with a number of philosophers who have discussed reflection (cf Ryle), he assumed it was highly rational and controlled. He defined reflective thought as:

Active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and further conclusions to which it leads ... it includes a conscious and voluntary effort to establish belief upon a firm basis of evidence and rationality. (Dewey, 1933, p9)

Dewey considered that reflection involves an integration of attitudes and skills in methods of inquiry; that neither attitudes nor skills alone will suffice (Zeichner, 1982). Although we acknowledge a great debt to Dewey, we do not fully follow his path. In particular we give much greater emphasis to the affective aspects of learning, the opportunities these provide for enhancing reflection and the barriers which these pose to it.

In order to explore this model in more detail we shall consider each aspect of it in turn and focus on those issues which in our view are important in ensuring that the process of reflection is an effective one. First, we will examine some of the characteristics of learners and the significance of these for their response to the initial experience. As by definition the experience which will be processed has to be experienced by the individual, what the learner brings to the event is essential to an understanding of what occurs. Second, we will look at what we regard as the three major elements of the reflective process itself: returning to the experience, attending to feelings, and re-evaluating the experience. These elements are concerned with how the learner works on the experience, links new knowledge with old, re-examines the initial experience in the light of his or her own goals, integrates learning into his or her existing framework, and rehearses it with a view to subsequent activity.

The Learner

The characteristics and aspirations of the learner are the most important factors in the learning process. The response of the learner to new experience is determined significantly by past experiences which have contributed to the ways in which the learner perceives the world. The way one person reacts to a given situation will not be the same as others and this becomes more obvious when learners from diverse backgrounds work together.

Those who approach the new learning experience from a history of success in similar situations may be able to enter more fully into the new context and draw more from it. The person who is adequately prepared in the particular area of learning can approach it with feelings of competence and confidence and is more likely to find it a rewarding experience at the time and will be drawn into it more easily. A history of positive associations with teachers can also contribute to productive involvements in new learning experiences. The building of a good climate in which to conduct learning activities is directed towards bringing these positive attitudes to the fore.

It is also necessary to take into account negative experiences from the past. An example of the unique response of an individual and how this can affect teaching plans is shown by a recent incident. In one of our classes a group of adults was shown a film about the life of the German theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer. It was intended that this should stimulate discussion on some of the values implicit in his work. After the film there was a period of discussion in small groups focusing on a series of questions provided to help each participant formulate his or her own response to the values presented. After the exercise was complete the group commented on the activity. Most of them had responded to the film in the way anticipated by the teacher. However, in one case the entire experience had been quite different. During the film there had been very brief flashes of atrocities inflicted in concentration camps: these appeared to have been included to provide a background for the issues presented in the film. However, they were sufficient to arouse in one participant a reaction quite unlike that of the others. This person, as a child, had experienced at first hand atrocities similar to those portrayed, and the film's brief flashes of them had caused her to relive those past events. Her response to the intellectual values presented in the film had been drowned in the emotional upsurge that had been triggered in her. The teacher's facilitation of reflection on the experience of the film in no way related to what this person had experienced, and, for her, the whole exercise was of a dramatically different nature from that of the others.

This example may appear a little atypical, but in all situations we find that our perceptions of events are conditioned by past experience which has shaped our response to the world around us, and that knowledge of how this has affected us in unknown or unknowable to a teacher. Less vivid examples of the above occur every day in other ways. A student who has had unpleasant experiences in, say, a mathematics or science class may, when exposed to similar situations in the future, experience again the same feelings of discomfort. These can interfere with the process of subject-matter learning as the student may become so preoccupied with emotional reactions that the new information presented by the teacher is not clearly perceived. The learner does not relate to the mathematical or scientific content but rather responds covertly to the past humiliation and embarrassment. This emotional load can carry over into the learner's processing of the subject, and unless some way can be found of resolving these feelings there will be no new learning of the content in question. Such negative reactions to formal classroom situations are more common than we usually care to admit. Of course, there are also the mathematics students who have had enjoyable experiences and for whom maths is fun. After the particular class is over they continue holding their positive attitude; they may be good at mathematics not because of any special natural ability but because they feel comfortable about learning it.

George Kelly (1955) in his personal construct theory refers to the individual and unique perception of each person. He highlights the differences in individual perception and response to the one event and identifies the need for teachers to be aware that what is in their heads is not necessarily translated to the heads of their students. In Kelly's view objects, events or concepts are only meaningful when seen from the perspective of the person construing their meaning. This suggests that techniques to assist reflection need to be applied to the constructions of the learner, rather than those of the teacher. A similar emphasis can be found in the work of Paulo Freire (1970) although he stressed cultural rather than psychological factors in learning. His team of literacy workers adopted the view that learners have a personal perception of the world which is culturally induced, so that their personal meanings or constructs can only be comprehended in their unique social and political context. Both Kelly and Freire highlight the centrality of individuals’ perceptions in learning. As Abbs (1974) puts it, ‘one must again and again return to the person before us’.

One of the most important areas of learning for adults is that which frees them from their habitual ways of thinking and acting and involves them in what Mezirow (1978, 1981) terms ‘perspective transformation’. This means the process of becoming critically aware of how and why our assumptions about the world in which we operate have come to constrain the way we see ourselves and our relationships. He suggests that there are two paths to perspective transformation: one is a sudden insight into the structure of the assumptions which have limited or distorted one's understanding of oneself and one's relationships; the other is directed towards the same end but it proceeds more slowly by a series of transitions which permit one to revise specific assumptions about oneself and others un...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: What is Reflection in Learning?

- Chapter 1: Promoting Reflection in Learning: a Model

- Chapter 2: Autobiographical Learning

- Chapter 3: Writing and Reflection

- Chapter 4: Debriefing in Experience-based Learning

- Chapter 5: Reflection and Learning: the Importance of a Listener

- Chapter 6: Reflection and the Development of Learning Skills

- Chapter 7: Reflection and the Self-organized Learner: a Model of Learning Conversations

- Chapter 8: Judging the Quality of Development

- Chapter 9: The Role of Reflection in a Co-operative Inquiry

- Chapter 10: Action Research and the Politics of Reflection

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reflection by David Boud, Rosemary Keogh, David Walker, David Boud,Rosemary Keogh,David Walker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.