1

The appeal of community, museums and heritage

Community heritage is a notion that is referred to so often and so effortlessly that one might consider it unhelpful to unpick the association – over-analysis might cause the essence of the relationship to be lost when the pieces are pulled apart and considered individually. That is not the goal of this chapter; instead, its purpose is to explore that relationship, to reveal the nature of the connections, and to discover why the two so often come together. The chapter uses recent experiences of how community has been associated with heritage, museums and display to demonstrate the appeal of one for the other.

This chapter begins with a consideration of why the idea of community has been integrated with museums and heritage, both by people inside the museum and by groups who independently pursue heritage and museum projects. With regard to the former, community is shaping museum initiatives; with regard to the latter, museum activity is a means to express community identity. It is the contribution of museums to identity that is the theme of the second section. Since the beginning of museums, their display, architecture and presence have been a means to communicate the identity of the place and people at their core. The third section looks to how a greater awareness of community and community concerns has influenced museum practice, ranging from the types of exhibitions mounted, to the development and management of collections, as well as staffing and new programmes in museums. The closing section looks to how these various aspects of how museums and community have come together have caused us to rethink what a museum is and what its potential might be. As a contribution to this study this chapter lays the foundation of the appeal between museums and community that is the basis for many of the initiatives explored in later chapters.

The currency of community

In museum and heritage studies, community has been considered in numerous ways, from involving the people whose histories and cultures have inspired the formation of collections through to developing an awareness of the shared responses of people to exhibitions and collections. There is now increased use of the phrase ‘community museology’1 and greater knowledge of the complexity of museum audiences. On the ground we can consider the relationship between museums, heritage and community in two ways. First, we can look to the rise of community within the official museum sector, which can be considered as the professional museum sector such as advisory bodies, central or local government funded museums, or private museums with accredited status. This would include museums that are adopting professional standards of best practice and which have or seek the status of such museums. These institutions are more likely to follow the recommendations of professional bodies and to be influenced by government policy. Following on from the rise in profile of policy relating to community, it is now commonplace for museums to appoint a community outreach officer, or at least to have a member of staff with that responsibility. Often such museums have community galleries, may mount exhibitions targeted at specific community groups or, indeed, may have developed a community policy. Many of the established, state-run and ‘official’ museums are willingly involved in community activity, be it community consultation or working with communities on exhibitions; or they may take seriously the impact they may have on their community. Museums Australia, for instance, advocates the formation of ‘community collections’, informed by ‘the keepers of community knowledge’.2 In the US the Museums and Community Initiative, led by the American Association of Museums, was used as a means to gather information about how communities regarded museums and to develop a ‘toolkit’ that would enable museum staff to work better with the community.3 We should remember that within the official museum sector there is great diversity. In the UK, for instance, we should distinguish between national and local authority museums, each of which will have a very different history, mission and relationship with its public. In relation to the issues of governance, national museums are centrally funded and their public is across the UK, with pronounced diversity. The future of these museums is closely tied to central government policy, and as attitudes in government shift so too will priorities for the department funding these museums. Local authority museums, run by local, district or city councils, are often closer to a specific geographical electorate, and in order to continue to receive political support they are aware that they need to reach as wide an audience as possible. As a result they may find it easier to get a clearer sense of who their communities are, the nature of those communities, and how best to respond to their needs.4

The second area to consider is the interest in heritage and museum activity emerging from the communities themselves, and we can refer to this as the ‘unofficial’ museum sector. Community groups, often with no museum training and little care for standards of museum practice (such as how best to write a text panel), often produce the most interesting, passionate and relevant exhibitions or collections reflecting their own experiences and priorities. In most cases, this community–heritage engagement has not been triggered by policy guidelines or recommendations; instead, it comes from members of the community and is inspired by their own perceptions of what they need and how this can best be achieved. There are other characteristics of this form of community heritage initiative: they are sometimes transient, often personality led, and frequently only best used and known amongst the community from which they emerged. They are often highly independent and subject to a different form of scrutiny. Rather than being guided, monitored and even restricted by professional museum standards, expectations and the glare of peers, it is more likely that this form of governance will come from within the community itself. Therefore, community initiatives will develop reflecting the community, as defined by its leaders, incorporating its strengths, as well as weaknesses. The less attractive characteristics of community may not be escaped: its exclusiveness, the boundaries, and its limits. Some of this will be related to why a community interests itself in heritage. Rarely will a community group participate in heritage without reason: there are often distinct motivations behind such activity that reflect the needs and aspirations of the community. Collecting oral histories, the creation of exhibitions and the formation of local history groups will often be drawn into the pursuit of other goals that can be social, economic or political.

Although, for ease of understanding, I have presented two forms of community heritage, in reality it is far more complex than that. It is also the case that a community heritage initiative, emerging from the unofficial sector, can, when longer established, take on the characteristics of the official sector. Over time, a community initiative may well become more closely involved with the established heritage sector, maybe by adopting professional standards or linking with policy initiatives emerging from the sector. Or the established heritage sector may well support a community initiative, and be prepared to keep its distance, so allowing the initiative to emerge independently. It is also the case that the idea of a community museum differs in different contexts. In the UK the Leicestershire County Council Community Museums Strategy, for instance, has been set in place to support voluntary and independent museums in the region. Most of these receive no regular funding, are run by volunteers and are very closely linked to the local communities. Many relate to local historical societies and exist due to the enthusiasm of a few key members. Leicestershire County Council has appointed a Community Museums Officer who, with a grant budget, aims to support these museums in the areas of standards, audience development, sustainability and learning.5 A similar concern for introducing standards to the independent museum sector is found in Canada and is illustrated by the ‘Standards for Community Museums’ initiative in Ontario6 or the ‘Community Museums Assistance Program’ in Nova Scotia.7 In these examples the majority of community museums are local and independent and have been established to communicate the history of the area and the passions of local individuals.

This differs very greatly from the idea of a community museum or centre that has grown popular in Australia or South Africa, for example, where they have been developed with far more radical and social agendas in mind. Moira Simpson discusses the use of museums amongst Australian Aboriginal communities. These museums, she writes, may incorporate aspects of conventional museums, but they are used to counteract traditional museology by omitting or including activities or methods important for their local agendas. In the Aboriginal context this may be a means to protect their communities from intrusion – the museum becomes a ‘tourist stage’ – or to assert cultural autonomy. The museum may be a means to articulate social and political concerns, contest official histories, and present alternative narratives. It may also act as a form of education and reconciliation between different peoples.8 These museums, by being closely linked with community objectives, can also be identified as political spaces. Davalos, for instance, describes examples of the formation of community museums in the US resulting from a sense of exclusion and as a form of resistance. As advocates for ethnic communities, these museums are often directly involved in community development, political action and protest.9 In their description of new museums in South Africa, Mpumlwana et al. refer to them as community resources engaged with the goal of political democratization.10 Community can also be taken as an example of the politicisation of the museum and, as noted by Karp,11 this can raise acute moral dilemmas. At times community heritage may result in requests that are oppressive to another community. A group may have a very exclusive idea of how to represent their particular community, which rejects certain members or expressions of local identity. Such cases will encourage us to ask who is speaking for community and why, and to ascertain whether all demands made by community in relation to heritage are equally valid.

A museum that straddled the idea of a museum originating from established practices, but attempting to take on a more radical agenda, is that of the example of the Anacostia Museum Columbia and its history reveals the tensions that can arise from these different perspectives. The museum was established in 1967 in one of the poorest areas of the District of Columbia and, although always linked to the Smithsonian Institution, in its original format the museum was very much a community initiative that was well connected with the local African American community.12 In her account of its history, Portia James described the museum as having developed along its own independent lines, quite different from many official museums at the time: it involved local community activists and leaders; informal advisory groups were populated by local groups; and management structures were kept simple: ‘there were no curatorial or research personnel and, initially, no departments’. In the early years, an individual identity, separate from the Smithsonian, was deliberately maintained. James describes local community members as regarding the museum as a means to share ‘their insights, their perspectives and their history’, and their interest as inverting the Smithsonian’s original mission in order to suit their needs.13 However, with time, the museum entered a new phase triggered by the professionalisation of its activity. This phase saw a reduction of participation by community members, the museum moving away from a relatively busy area and into a nearby park, and more sophisticated and costly exhibitions. Maybe most revealing was a change of name that dropped the word ‘neighborhood’. In James’s account, mainstreaming the museum ‘weakened the museum’s structural ties to the community it served’.14

The example of Anacostia Museum raises important questions for those interested in the relationship between museums, heritage and community. Heritage has multiple purposes and the motivations for participation in heritage activity will differ according to one’s position in relation to it. There will also be numerous interpretations of the function, impact and success of various projects and how those might be measured and valued. The community group might regard a short-term heritage project, perhaps a collection that has been brought together for a short period, as a success. A professional museum curator, in contrast, might judge success on longevity and permanence. There are many different ways of ‘doing’ museums and heritage, and one judgement on what is appropriate will often be different from another. Sometimes, concern with the professionalisation of collecting or exhibiting practices may well be missing the point of the community initiative. I experienced this when I visited the museum in the Apprentice Boys Memorial Hall, Northern Ireland, along with a group of people that included a local museum curator who was well aware of best practice in collections care, display and handling.

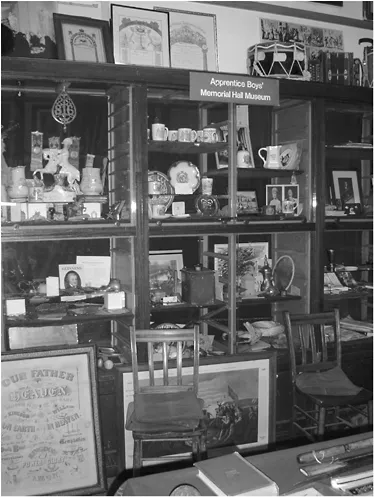

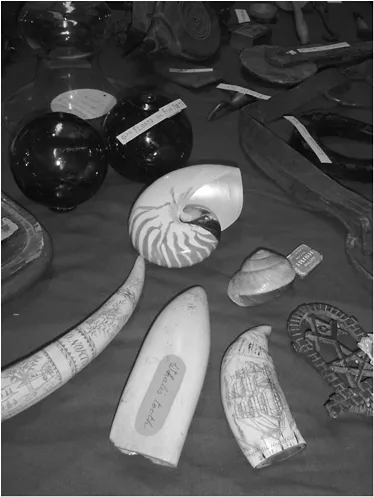

The Apprentice Boys is a members-based group that was established in the early nineteenth century to mark the Siege of Derry in the 1680s. The collection on display was formed by a member of the organisation and is held in one of the most important meeting rooms within the Memorial Hall. Over the years the museum has become a disparate collection of artefacts, some of which are related to the social and political history of the locality while other items simply make up a most bizarre cabinet of curiosities. In the summer the museum is open to the public one day a week and some of the most historically important objects within the collection are on open display, for visitors to handle (see Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). Documentation of the collection is minimal and concern for collection care issues in little evidence. For the professionally trained curator amongst my group this was anathema and, indeed, made his visit very uncomfortable. Although I have great respect for the best of museum standards, in this case their adoption was not the primary concern of the collector and would perhaps contravene the aims of the collection. If it was suggested that the collections should be moved to the nearby city council museum, which employs high standards of collections care and display, this would lessen the value and meaning of the collection for the local community group. The fact that community members, who care greatly about the history of their local area, can regularly and easily handle items dating from the Siege and later historical events is important, and the ability to hold local meetings in the community hall, amongst the artefacts that inspire the group, is of immense value. For this group the material culture in context is a means to construct community identity and form bonds between members, both past and present. The objects are the tangible link between imagined communities – they are the link to people the members can never meet.

Museums and formation of identity

Whether one’s interest is increasing the profile of community within the official museum sector or understanding better the role of heritage in community-led initiatives, one can sense a re-evaluation of how museums are defined and engaged with. Museums are no longer only being established in imitation of the grand Louvre or Hermitage expression of a museum as high culture, created in the eighteenth century. Instead, the broader concept of the folk, eco or living museum is gaining popularity. This early idea of a museum and its collection was born from activity of the elite: vast collections were created by royalty and the upper classes, packed with the products of the Grand Tour. These were the hobby museums that became the pastimes of the leisured classes. Recent research into the history of collecting in nineteenth-century England has shown how an interest in developing natural history and antiquarian collections occupied the minds of these men. It is these people whom we should acknowledge for the wealth of many of the county museums as well as the national collections in the London capital. In Scotland and Ireland a similar tradition also emerged, with gentlemen’s clubs forming the early collections of the Scottish Antiquaries Museum and the Royal Museum of Edinburgh, now part of the National Museums of Scotland, and the Dublin Museum of Science and Art, renamed the National Museum of Ireland early in the twentieth century. Still today collecting is a popular activity, although its expression may not be so recognisable to the collectors of the past. A new form of contemporary collecting has emerged outside museums. This is not the art and archaeology found in the museums we may frequent; today’s collectors include those who are occupied with building collections of ephemera – be it packaging, badges or posters.

Figure 1.1 The Apprentice Boys Museum, Apprentice Boys Memorial Hall, Londonderry, 2006

Figure 1.2 The Apprentice Boys Museum, Apprentice Boys Memorial Hall, Londonderry, 2006

Museums are not only about the collections they house – they are also about the sense of the past they represent. Museums symbolise culture, identity and heritage. For new nations the story told in museums by the objects on display can endorse a political message, and can give a tangible link to a frequently elusive concept. The method by which nationalism has employed museums reveals much about how they hold their significance. An aspect on which the many theories of nationalism agree is that a sense of ‘the past’ plays an important role in fostering national identity. According to how one understands nationalism, this past may be one that is reinterpreted, revived, invented or imagined. In each case, however, references to past events and heroes are used to unite the people around the idea of ...