- 400 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Bringing the reader the very best of modern scholarship from the heritage community, this comprehensive reader outlines and explains the many diverse issues that have been identified and brought to the fore in the field of heritage, museums and galleries over the past couple of decades.

The volume is divided into four parts:

- presents overviews and useful starting points for critical reflection

- focuses more specifically on selected issues of significance, looking particularly at the museum's role and responsibilities in the postmodern and postcolonial world

- concentrates on issues related to cultural heritage and tourism

- dedicated to public participation in heritage, museum and gallery processes and activities.

The book provides an ideal starting point for those coming to the study of museums and galleries for the first time.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Issues in heritage, museums and galleries

A brief introduction

Gerard Corsane

Introduction

Where does one start to introduce the myriad of issues that have been identified and brought to the fore in relation to heritage, museums and galleries over the past couple of decades? In a postmodern and postcolonial world, the range of issues has proliferated and spread, especially with the increased information flow and possibilities for exchange of ideas that have accompanied the development of new communication technologies and new media. Discourses on heritage, museums and galleries have become a massive, complex and organic network of often loosely articulated understandings, ideas, issues and ways of perceiving things; a network that is fluid, dynamic and constantly reconfiguring itself as individuals critically reflect on and engage with it. In addition, the way in which individuals reflect on the issues will depend on their starting points. Practitioners, academics, government officials, along with users and non-users of cultural and heritage institutions, will each have different approaches. However, although it is now accepted that no two people will share exactly the same list of perceived issues in the same order of priority, there are a number that appear to have currency in recent and present debates and discourses in heritage, museum and gallery studies. Many of these issues are associated with challenges to modernist Western principles and practices, along with calls for greater transparency and democratization. The selection of material in this volume has been informed by this, and by the range of material included in the suggested further reading list.

To assist in providing a framework for the reader to engage with some of the issues, this volume has been divided into four parts. Part 1 contains a selection of chapters relating to heritage, museums and galleries that present overviews and useful starting points for critical reflection. The items included in this part offer broad contributions that introduce the terminology and concepts relating to recent and current issues. The intention of Part 1 is to provide the reader with a general platform before certain key issues are introduced in more depth in the remaining three parts of the book. Lumley (Chapter 2) and Graham, Ashworth and Turnbridge (Chapter 3) provide a valuable background for understanding many of the issues relating to heritage more generally. Harrison (Chapter 4) and Stam (Chapter 5) identify and chart a number of the key challenges and trends in recent museological thinking that have influenced museum development over the past couple of decades, whilst Duncan (Chapter 7) and Whitehead (Chapter 8) bring useful perspectives on the relationships between people and art museums and galleries. Gurian (Chapter 6) makes an important contribution in showing how the boundaries between museums and other sites and media that store and shape memories are blurring, potentially leading to the reconfiguration of the heritage and cultural sector. The relationships between these sites and individuals or social groups, in terms of memory-making and the sharing of memory, are covered in Crane (2000) and Kavanagh (2000), and relate to Davison (Chapter 14).

Part 2, which has the largest number of articles, aims to draw the reader’s focus more specifically to a number of selected issues of significance. Parts 3 and 4 then go into further depth on issues in two particular areas: Part 3 concentrates on issues related to cultural heritage and tourism and Part 4 is dedicated to public participation in heritage, museum and gallery processes and activities.

In Part 3, the contribution from Prentice (Chapter 19) shows the range of attractions that can be considered in terms of heritage tourism. He makes some useful observations about the profile of visitors and suggests interpretative strategies that could be used to widen the visitor base. Richter (Chapter 20) follows with a discussion on issues surrounding the political dimensions currently associated with heritage tourism. Each of the final three chapters by Macdonald (Chapter 21), Hitchcock, Chung and Stanley (Chapter 22) and Witz, Rassool and Minkley (Chapter 23), discusses the construction and presentation of heritage products within different political, economic, social and cultural contexts. With each of these it is interesting to consider who drives the processes of construction and presentation and how the different types of visitors and users—with varying expectations—consume the heritage tourism products described.

Finally, the reason for placing the articles in Part 4 at the end of the volume is that issues relating to social exclusion (Newman, Chapter 24), the co-creation of the civic museum (Thelen, Chapter 25), the approaches of the neighbourhood museum (James, Chapter 26), the negotiated community-based museum (Gordon, Chapter 27) and the principles of ecomuseum models (Davis, Chapter 28) are concerned with democratization. These chapters complete a circle that will bring the reader back to a model, to be proposed below, as a way of developing an ideal democratic overall process for heritage, museum and gallery work.

Overall process of heritage/museum/gallery work: a proposed model

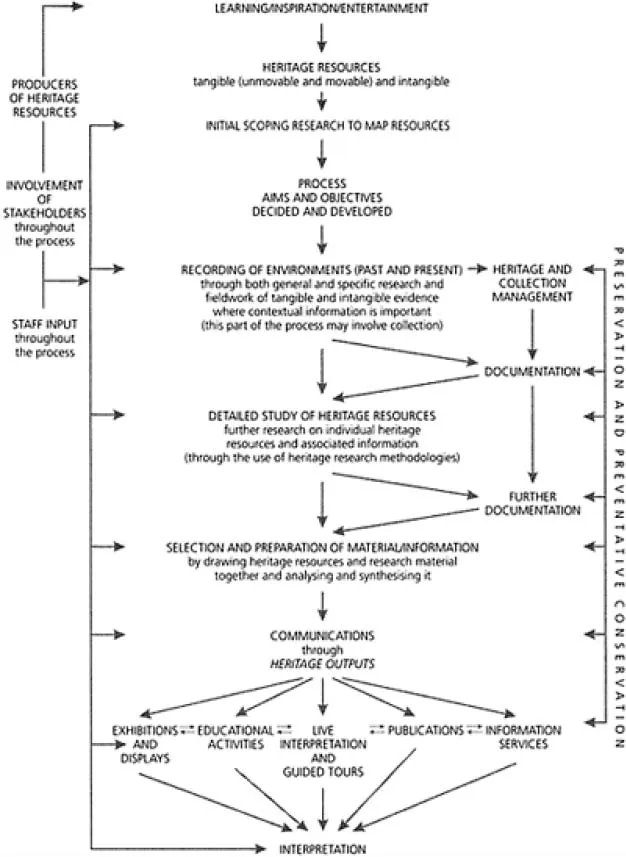

The proposed model (Figure 1.1) emphasizes the importance of public participation in all stages and activities of the overall process of heritage/museum/gallery work, from involvement in the activities themselves to the decision-making processes that both lie behind these activities and connect them. This model provides a framework that can be used to bring together many of the key issues that are raised in the chapters included in Part 2 and, after the model has been discussed, these issues will be considered in turn.

Although the process may appear very linear and rigid in the diagram, this is not the case in reality. The process should be viewed as being circulatory and dynamic in character. At any point during the process, one must be aware of the importance of allowing for feedback loops, which can further help to expand areas of the process already worked through.

The model takes as its starting point the notion that heritage, museum and gallery work is performed to provide vehicles for learning, inspiration and entertainment. Taking note that there would have been processes behind the original formation of cultural practices, material and expressions, the overall process in the model works from the heritage resources at one end through to the heritage outputs that are communicated at the other. This central line of activities performed in the model, and the acts of interpretation that follow, denote the processes of meaning-making in heritage, museums and galleries.

Fig. 1.1 Model of the overall process of heritage/museum/gallery work

Ideally, throughout the process, practitioners work with representatives from different stake-holder groups and ‘communities’ in consultation and negotiation (see arrows down left-hand side of model in Figure 1.1). Together, they identify appropriate heritage resources through initial scoping research. This initial research provides the basis for developing aims and objectives that guide the ongoing process, starting with activities where ‘environments’ are recorded and documented (see e.g. Kavanagh, 1990). The word ‘environment’ is used here in its broadest meaning and includes natural, social, cultural, creative and political contexts, and the relationships between them. This level of recording will require the use of a range of different research methodologies and techniques in order to gain both general and specific information. It will involve ‘fieldwork’, which again is used in its broadest sense to mean recording heritage resources wherever they may be found. This may involve documenting and studying anything from natural habitats and ecosystems, urban and rural landscapes, archaeological and heritage sites, the built environment, suites of material objects, archival material and artistic forms of expression—through to different knowledge systems, belief patterns, oral traditions, oral testimonies, song, dance, ritual, craft skills and everyday ways of doing things. The activities of recording and documentation at this level may involve the active collection of movable objects, as is the case with most museums, or it may require the relocation of larger items, such as buildings, for open-air museums. Wherever this takes place, the documentation activities are of even more importance, as associated contextual information is needed for material that is moved from its original location.

Following these first-level recording and documentation activities, the research can become more focused on the individual aspects and sources of evidence. For example, in museum research, material culture and artefact study approaches are employed to read meanings out of (and into) the material (see e.g. Pearce, 1992, 1994; Schlereth, 1982, 1990; Lubar and Kingery, 1993). In all of this documentation and research, information is produced and is fed into the second-level (or archival) documentation that becomes part of the heritage and collection management line of documentation, denoted by the arrows down the right side of Figure 1.1.

The results of all of this documentation and more detailed research then goes through a process of selection and preparation and become the communication outputs, which are communicated through a range of different, but interlinking, media. This final part of the meaning-making process involves a certain amount of mediation as decisions are made about:

- the selection of material and information;

- the construction of the messages to be communicated;

- the media to be used in the communication.

It is at this stage that the input from stakeholder groups (being all those that could have an invested interest) and communities may be most crucial, although they must be included throughout the overall process.

Traditionally, these last stages of the processes have been viewed as the activity of interpretation. However, as will be seen later, the acts of interpretation of the heritage, museum and gallery outputs involve the users of these products—the ‘Visitor’ (see also Mason, Chapter 16).

Parallel to the central process of meaning-making runs the process of heritage and collections management, which involves taking care of the heritage resources through documentation, preservation and conservation of the material and associated information. What is undertaken in this parallel process should also be negotiated with stakeholders. In addition, it should be noted that whatever is done in this process will have some form of impact on meaning-making.

Finally, when considering the model, two further points need to be made. The first and most direct is that, ideally, the process should allow for feedback and evaluation loops. Second, it needs to be understood that there are a range of external factors that will influence the process. These factors could be set by political, economic, social and cultural conditions and agendas.

Placing current concepts and issues against the overall process

Many of the concepts and issues that relate to current discussions in heritage, museums and galleries—and which are raised throughout the chapters in this volume—may appear to be more specifically connected to a particular component of this overall process. For example:

- some concepts and issues relate more clearly to the actual cultural property and heritage resources themselves;

- others are linked more closely to the heritage outputs as communicated through different media, products, public programmes and commodities, along with how they are used and consumed in a variety of ways;

- finally, there are those concepts and issues that are associated with the range of sub-processes associated with the overall process outlined above.

It should be noted here, however, that the sub-processes in the third component can be located at different points within the overall process. Certain sub-processes are more closely allied to the actual production of heritage resources, which can never really be seen as ‘raw’, as they have been invested with meanings during their original formation. In terms of heritage resources, there are also a wide range of issues associated with the sub-processes of selection of what is deemed worthy of preservation and conservation, along with the sub-processes allied to collecting activities and the documentation of associated information. These revolve around the questions of: who makes the decisions; how are they informed and what criteria are used when making the selection?

Other sub-processes can be positioned further along the system on either side of the heritage outputs. There are those that are part of the final mediation, construction and packaging of the outputs (e.g. label-writing processes, scripting of re-enactment live interpretations, or the design of educational activities) and others that relate more to how heritage outputs are consumed and utilized by the heritage visitor, or user. In addition, there are those that can lie in the overall process somewhere in between the resources and outputs, and are linked more to the methodologies used in recording, research, and heritage and collection care in different contexts. Although many of the concepts and issues relating to these aspects of the system are contingent and in actuality cannot be easily separated out, the three components of the overall process can be used for convenience as a basic framework for introducing the different concepts and issues explored in the chapters in this volume.

At this point, it can be noted that many of the concepts and issues, wherever they are placed within this system, share a common feature in that they relate to notions of ‘ownership’—ownership of the cultural and heritage resources, ownership of the heritage outputs and ownership of the activities and sub-processes in between. With these notions of ownership come legal and ethical issues.

Intangible cultural heritage

Before going on to look at the more specific issues that relate to the ownership of heritage resources and cultural property covered in this volume, it may be useful to alert readers to a more general issue of current significance. Traditionally in Western models, heritage, museums and galleries have tended to concentrate their collection and preservation activities on material culture. Heritage has focused on the preservation and conservation of immovable tangible heritage, and museums and galleries on movable tangible heritage. However, more recently the heritage, museum and gallery sector is being encouraged to expand its notion of what heritage is, in order to take account of intangible cultural heritage. At an international level, the Section for Intangible Heritage within the Division of Cultural Heritage of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has been active in this area, with several key projects documented on the UNESCO web site. The most recent of these has been the adoption of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage at the thirty-second session of the UNESCO General Conference on 17 October 2003. The definition of intangible culture heritage used in the convention states that:

The ‘intangible cultural heritage’ means the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage. This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity. For the purposes of this Convention, consideration will be given solely to such intangible cultural heritage as is compatible with existing international human rights instruments, as well as with the requirements of mutual respect among communities, groups and individuals, and of sustainable development.The ‘intangible cultural heritage’, as defined ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 Issues in heritage, museums and galleries A brief introduction

- Part 1 Heritage/Museums/Galleries Background And Overview

- Part 2 Highlighting key issues

- Part 3 Heritage and cultural tourism

- Part 4 Democratizing Museums And Heritage

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Heritage, Museums and Galleries by Gerard Corsane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Museum Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.