![]()

1

Forces for change

Museums and galleries throughout the world are at a point of renewal. New forms of museums, new ways of working with objects, new attitudes to exhibitions and above all, new ways of relating to museum publics, are emerging. At the end of the twentieth century, old structures are being replaced to prepare for a new century. Many social institutions are reviewing their roles and potentials, and museums and galleries are among them.

What are the functions of museums likely to be in the twenty-first century? One thing is certain. Museums must develop a clear social function. During the 1990s a new age has dawned, a knowledge-based age that will replace the post-industrial age that has existed for the last hundred and fifty years. As the heavy plant of industrial production is replaced by the micro-circuits of the computer, the emphasis changes from the production of technology to the production of ideas, the pace of knowledge transmission increases, and possibilities for intellectual action multiply. Knowledge races around the world in a micro-second, information is accessed in new ways, and new levels of interconnectivity become possible.

What is the role of the museum within this cultural shift? As electronic media move centre-stage, what is the function of the three-dimensional object? As the importance of knowledge and information grows, how can museums play a genuine part in the production and dissemination of knowledge? How should museums renegotiate and redefine their functions? What is the way forward for the twenty-first century?

During the next decade, the relationship between the museum and its many and diverse publics will become more and more important. And this relationship must focus on genuine and effective use of the museum and its collections. In the past, museum visitors have been content to stroll through the displays and have rarely sought more than a tangential visual experience of objects. Now, there is a clear and consistent demand for a close and active encounter with objects and exhibits. A physical experience using all the senses is called for.

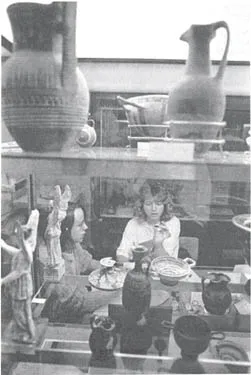

Plate 1 The close examination and handling of a small fragment helps in the seeing and understanding of the archaeological artefacts displayed in the glass cases. These traces enable students at Liverpool University to relate ideas drawn from the objects of the past to their own present and future lives.

Photo: Howard Barlow.

Increasingly this experience is expected by visitors to be of immediate personal relevance with an interaction which is sustainable for several minutes and which results in a clearly identified knowledge gain. When this rapid and explicit benefit is not available, museums are not popular; where displays, discovery centres, responsive exhibits, dramatic performances and interactive videos enable this experience, museums are overwhelmed with appreciative vistors.

How therefore can museums, and perhaps more problematically, art galleries, offer meaningful experiences for their visitors? What conceptual changes are necessary in order for museums to consolidate a powerful new future?

These questions will be answered throughout the course of the book. This chapter will examine a number of forces for change that museums can harness in their development towards becoming relevant institutions for the twenty-first century. Forces for change include an expansion of the museum’s traditional educational role, moves towards being more user-centred, and the response in museums to greater accountability and competition.

An expanded role for museum education

The United Kingdom Museums Association asserts in its National Strategy for Museums that as an educational resource, museum collections constitute a national asset that has been consistently undervalued (Museums Association, 1991a:11). It is recommended that museums need to draw the attention of both central and local government to their educational strengths, and that an educational policy should be drawn up and regularly reviewed.

Museum education is too important to be left to the educators. It needs to imbue everyone who works in museums…the policy of any museum should be an education policy…education is a key component in every museum’s raison d’être.

(Pittman 1991:43)

Nigel Pittman, then Head of the Museums and Galleries Division of the Office of Arts and Libraries (the UK central government body overseeing the work of museums; now subsumed into the Department of National Heritage), here makes very explicit the expansion of museum education. Pointing to the founding purpose of many Victorian museums, Pittman states firmly that museum education today should be understood not merely as the provision of classes for organised educational groups, but should be seen as the shaping force behind a museum’s general policies and objectives.

As museums develop into institutions which collect, care for and communicate about objects, so the role of museum education is expanding. Museum staff in general are developing their roles as educators through the new approaches to displays that are being developed, through considering the educationalpotential of new museum developments and through a heightened awareness of the museum’s public. In a great many museums in Britain at the present time, the staff responsible for education are part of the senior management team, contribute to the scheduling and planning of exhibitions and other events, and take responsibility for the management of buildings and staff (Hooper-Greenhill (ed.), 1992). In the development of new relationships with audiences, it is often the education staff who are able to take the lead through their experience with museum visitors.

In Australia and the United States, the concept of the ‘audience advocate’ has been developed (Duffy, 1989; Hooper-Greenhill, 1991a:190–3). The ‘audience advocate’ acts as the person responsible for considering the needs of all sectors of the audience as new projects are developed. The ‘audience advocate’ researches the actual and potential museum audience, makes links with appropriate experts in order to develop knowledge and understanding of specific target groups (such as those with a particular disability), monitors new exhibitions and other projects, supplies audience-related information to other staff as appropriate and evaluates all aspects of the museum, its exhibitions and educational programmes in relation to visitor requirements.

As this new staff role is introduced to Britain, it has been variously considered within education or marketing departments, or, as at the Science Museum, London, is placed within a new Interpretation Unit, which includes those researching the needs of audiences (audience advocates), education staff, facilitators and enablers working with interactive displays, and a drama team.

In America, a group of museum educators, stimulated by the American Association’s 1984 report Museums for a New Century (Commission on Museums for a New Century, 1984), formed a task force to consider the development of museum education in American museums and galleries. The initial objectives for the task force were:

• to describe the critical issues in museum education;

• to recommend action that will strengthen and expand the educational role of museums in today’s world;

• to outline an on-going role for museums, professional associations and other appropriate organisations in ensuring that the recommendations are carried out.

(Museum Education Roundtable, 1992)

The discussions of the task force quickly moved from the discussion of museum education as a department within a museum to the assessment of education as the mission of the museum. The report of the task force, Excellence and Equity: Education and the Public Dimension of Museums (American Association of Museums, 1992), initially proposed that education was the primary responsibility of museums, but the report has been accepted by the American Association on the grounds that education is a primary reponsibility of museums.

The title of the document Excellence and Equity acknowledges both scholarship and public service, expert knowledge and outreach, accountability towards both collections and people. Although perhaps the document (in adopting a instead of the) did not go far enough for the members of the task force, issues about the balance of objectives and resources in museums and galleries were raised. Where funds, for example, are to be equally distributed between the demands of excellence and of equity, this will generally mean a redistribution of resources towards the provision of a public service, and it is strongly argued that both public provision and expert collection knowledge can and must exist side-by-side (Gurian, 1992).

The report represents an opportunity for museums and galleries to carry out a self-audit to prepare for the social realities of the twenty-first century, in full acknowledgement both of the democratic principle that people of all classes, ages, races and ethnic origins have the right to share the cultural patrimony available to them, and of the fact that museums have an obligation to reflect the nature of society in terms of collecting, the composition of their staff and governing body and their public programming (Swank, 1992).

Museums and the changing needs of schools

While the expansion of the broad educational role of museums and galleries is altering the balance of functions within museums, provision for both formal and informal education within museums is also changing and growing.

Histories have always been contested territories, and the power to define the past is one index of domination. As power and interest groups shift and fluctuate within societies, new approaches to history and the past are developed. The school curriculum frequently makes manifest these new approaches. In many societies today, the museum is part of this shifting of emphasis and perspective, and often takes on new functions in relation to school knowledge. Examples from two countries illustrate this.

As black South Africa struggles towards political power, the political and ideological infrastructure that sustained apartheid is crumbling. In terms of education, vast differences exist in the provision for black and for white children, which include differences in method of teaching, provision of resources and indeed in access to literacy. Some museums are determined to use their collections and resources to raise the standard of black education, and at Grahamstown the education department is staffed by both black and white museum officers, although at the time of appointment of the black officer, this was in fact illegal (Hall, 1992).

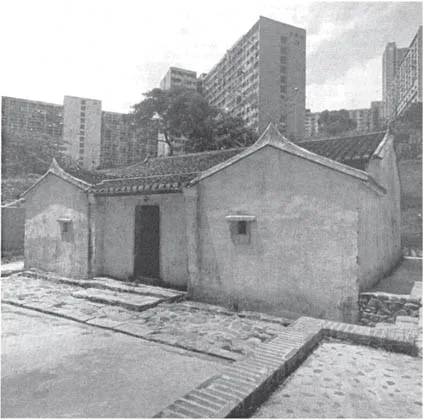

Plate 2 The Law Uk Folk Museum, the only village house left in an area of Hong Kong now covered with skyscrapers. As a unique survival of the farming community, this farm-house symbolises the simplicity and purity of the past as Hong Kong moves towards a complex and uncertain future.

Photo: Hong Kong Museum of History, Urban Council, Hong Kong.

A book has been prepared by the museum for teachers which identifies the historical myths that have been perpetuated in South Africa, myths such as: ‘Whites and Blacks arrived in South Africa at the same time’; ‘Black political ideas were inspired by Whites’; and ‘the Homelands correspond to the area historically occupied by each Black “nation” and their fragmentation was the result of tribal wars and disputes’ (Owen, 1991). The book makes suggestions about how history might be taught, focusing on historical methodology, and on history as a study of people, families and communities in the past. Teaching through objects is recommended as one way in which myths might be dispelled, and all children from all sections of society might begin to make relationships with the past. Museum objects, used in conjunction with photographs and documents, are seen as having the potential to promote a history relevant to the ‘new South Africa’.

Other institutions are also working to shift the balance of access to knowledge and skills. Johannesburg Art Gallery has recently developed the Imbali Teacher Training Project which aims to provide teachers with skills that will enrich their teaching of art within their own communities, which include Soweto, Kwa-Thema and Sebokeng. These practical workshops have grown out of and are sponsored by Women for Peace. The pilot teachers’ courses in 1989 focused on line drawing, mask-making and working with oil pastels. The success of these led to further workshops exploring print-making, kite-making and a mural painting project. These are recorded in the gallery’s annual reports.

In Hong Kong, a new approach to the teaching of history is focusing on ‘Hong Kong Studies’. In a nation which has up until now felt itself to be reaching forward rather than looking backward, but which is soon to experience radical changes in governance, the past has become newly important and has attained the status of something to be valued and cherished (P.Wright, 1992). This has meant an increase of relevance for the museums that hold the key to the past. The Law Uk Folk Museum offers an example.

Chai Wan (literally ‘firewood bay’) was a part of Hong Kong Island that until the late 1940s consisted of farmland, with several longstanding villages including Law Uk, Lam Uk, Shing Uk and others. The people of the villages were farmers, producing rice, fruit and vegetables which they exchanged with the passing fishermen for fish. In the small communities, a simple way of life existed. The Japanese occupation of 1941 began the process of change in the villages, which accelerated with the arrival of refugees in the 1950s, who settled in squatter huts on the hillsides. Since this time, the old villages have been cleared for redevelopment as Chai Wan has become a highly industrialised area, with the extension of the Mass Transit Railway System, and public housing estates.

The Law Uk Folk Museum is ‘the only village house left in the area and now becomes an authentic reminder of the early Hong Kong village house’ (Hong Kong Museum of History, 1990:24). The museum symbolises and represents the past of Hong Kong, and has become one of the sites where local studies can be carried out. Students can consider the difference between the old and the new ways, through the exploration of very different structures for living and working.

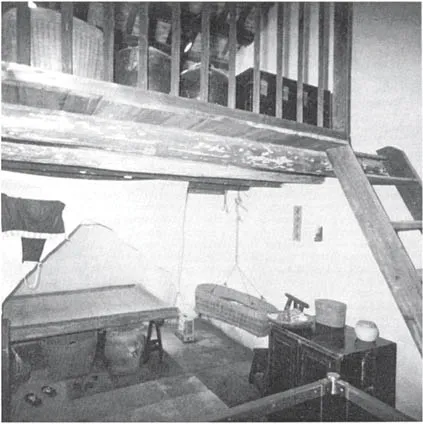

Plate 3 The interior of the Law Uk Folk Museum with a single room and a cock-loft above.

Photo: Hong Kong Museum of History, Urban Council, Hong Kong.

The integration of home and work can be observed in the internal rooms of the museum which served as both bedrooms and workrooms, with the roof spaces being used as cock-lofts.

In England and Wales, the introduction of the National Curriculum in 1988, which must by law be implemented in state schools, has opened up many opportunities for museums. The National Curriculum emphasises the use of primary sources in learning and is creating a demand at all levels for resources. The curriculum is enshrined in detailed documents, with specific programmes of study and attainment targets identified for each subject. These documents frequently refer either to the use of museums specifically, or to artefacts, specimens or the real things that museums are well able to provide.

In the National Curriculum for History, for example, at ‘Attainment Target 3: the use of historical sources’, children at level 2 (juniors) are expected to ‘recognise that historical sources can stimulate and help answer questions about the past’, and at level 3, ‘make deductions from historical sources’. At a later stage, level 6, children are expected to ‘compare the usefulness of different historical sources as evidence for a particular enquiry’ and at level 10 (older secondary pupils) ‘explain the problematic nature of historical evidence, showing an awareness that judgements based on historical sources may well be provisional’. The examples of how these skills might be demonstrated suggest using artefacts from a museum; for example making ‘deductions about social groups in Victorian Britain by looking at the clothes people wore’ (National Curriculum Council, 1991). Curricula from many other subject areas, such as science and art, also offer enormous and sometimes unexpected opportunities for museums of all sorts (Goodhew, 1989; Copeland, 1991; Pownall and Hutson, 1991).

In part, the relevance of the National Curriculum to museums and galleries reflects the work put into assessing and responding to the curriculum proposals by the Group for Education in Museums. GEM is the professional association for those in museums who work with education. Many of the recommendations made have been adopted by the curriculum working groups, who have in response made more specific references to the use of museums, galleries and sites, and have on occasions inserted references to the values of using objects in learning.

The committee of the Group for Education in Museums coined the acronym DAPOS (documents, artefacts, pictures, oral history and sites) to remind curriculum working-group members to assess their draft syllabuses to make certain that where relevant, these elements were included. This proactive stance by the group has resulted in a very direct relationship between museums and the National Curriculum. This is a major achievement and may well be seen in retrospect as creating one of the most successful ways in which the museums of the late twentieth century can demonstrate their use to society. With these clear opportunities now in place, it behoves museums to reappraise the support they give to schools to ensure that the needs of schools are met as they implement the National Curriculum (Audit Commission, 1991:6)...