![]()

PART 1

Marketing football in Europe

A The general state of football marketing in Europe

B The ‘Big Five’ market

C Is there a place for ‘small’ countries on the European football market?

![]() A

A

The general state of football marketing in Europe![]()

| CHAPTER 1 Building global sports brands: key success factors in marketing the UEFA Champions League Simon Chadwick and Matthew Holt |

Overview

In 1992 the European Cup was transformed into the UEFA Champions League (UCL), around which a new marketing strategy and brand identity were developed and implemented by UEFA, in partnership with TEAM Marketing. This chapter begins by examining the relationship between these two organizations and then considers the context within which the new strategy and identity were developed. Thereafter, each of the components used to create the Champions League brand are examined: the emphasis on European football history and heritage, the creation of a brand identity, the composition of a UEFA Champions League anthem, the use of imagery and symbols, and the creation of a new trophy. In the concluding section, issues pertaining to brand implementation, event management identity and the presentation of a television/media identity are addressed.

Keywords

branding, Champions League, sport product, strategic sport marketing, television and new media

European football: the emergence of the UEFA Champions League

Competition between the elite clubs of Europe can be tracked back to the 1950s. Following a series of friendly matches between Wolverhampton Wanderers of England and Honved of Hungary to decide Europe’s premier club, the French newspaper L’Équipe proposed the formation of a competition consisting of the league champions of each European nation, which was then constituted under the Union of European Football Association’s (UEFA) auspices. Thus the European Champion Clubs’ Cup, more commonly known as the European Cup, was born. The competition generated huge interest and popularity from the outset, and became a suitable platform for Europe’s greatest talents.

The competition remained unchanged for almost forty years, with entry limited to the holders and the national champions of each country. The knock-out format consisted of two-legged ties in which each club played one game at home and one away. By the early 1990s, however, the growth of television as a key medium of football consumption and the development of satellite and pay-television digital technologies led to an exponential growth in the revenues available to clubs. The composition of the competition thus became ripe for review. The knock-out format in particular, and the risk that popular clubs could be eliminated after one tie, was unacceptable to both clubs and broadcasters, who required a greater number of guaranteed games. Proposals aimed at transforming the competition had been raised at various points, most notably by the owner of AC Milan, Silvio Berlusconi, in the 1980s. In this context, UEFA took action to reconsider both the commercial and sporting aspects of its main club competition. In 1992, the European Cup was transformed into the UEFA Champions League (UCL), a hybrid competition comprising league and knock-out. The impetus behind this was a desire amongst both clubs and broadcasters for a greater number of guaranteed games, as a means to exploit new revenues.

In the political network of European football a constant state of tension exists between the elite clubs, looking for opportunities to increase revenues and greater autonomy, and the governing bodies, which look to control the wider interests of the game. UEFA’s control of the competition enables the organization to retain revenues for its own purposes, including the development of the European game. This is a source of grievance for the elite clubs. Gathered together in the G14 organization – a pressure group now consisting of eighteen of Europe’s major clubs – they lobby for greater influence. Clubs such as Manchester United, Real Madrid and Juventus generate enormous leverage from the size and loyalty of their consumer bases. Thus the control, format and marketing of the competition are subject to ongoing debate.

In this complex and unstable position, UEFA has had to rely on two separate strategies as a means of retaining control of its flagship competition. First, it relies on its position within the global framework of football governance and its historical role as the organizer of European club competition to buttress its legitimacy. Secondly, the ever-increasing demands of the clubs means that UEFA has been forced to produce a competition of quality and a reward to satisfy the competing clubs. UEFA has therefore taken responsibility for developing the competition both in sporting and commercial terms in order to adapt to the transformed commercial environment, and as a means to address the demands of the economically powerful clubs. In doing so, UEFA has formed a hugely successful commercial partnership.

UEFA and TEAM

The commercial growth of football, initiated and controlled by football’s governing bodies, has been facilitated by a small number of event and media management companies – most notably ISL (International Sport and Leisure) – long-term partners of both the world governing body FIFA and UEFA. The significance of these companies is such that they have been referred to as the ‘cement of network football: the go-betweens who line up corporate and media sponsors and stage manage the spectacle’ (Sugden, 2002: 67). In transforming European club competition, UEFA formed what has turned out to be a hugely successful alliance with two former executives of ISL. Recognizing the opportunities for growth, Klaus Hempel and Jürgen Lenz formed Television Event and Media Marketing (TEAM), based in Lucerne, Switzerland, as the vehicle through which the UEFA Champions League would be transformed. According to UEFA Chief Executive, Lars Christer Olsson (personal interview, 16 November 2004:

‘The development of the Champions League was, in my opinion, not so much driven by wishes from the bigger clubs, as the needs of the television companies … Hempel and Lenz were early in this process and they created with Johansson and Aigner [then UEFA President and General Secretary] the concept for the Champions League, based on the needs of television which means that the major markets had to be better represented.

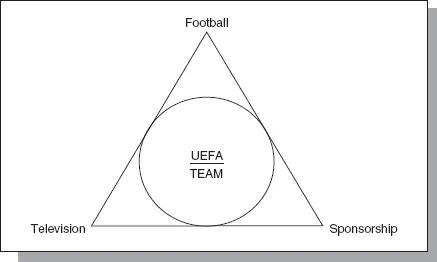

On instruction from UEFA, TEAM sought to apply a blueprint for sports marketing success by marrying the synergetic qualities of football, sponsorship and television, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. As Hempel explains (Ahlström, 2002: 18):

We spent three weeks at the Villa Sassa fitness clinic in Lugano and it was there that we worked for three hours per day on a new concept of creating a ‘branded’ club competition … We came up with a triangle formed by football, sponsors and broadcasters with UEFA and TEAM in the middle, harmonizing the interests and making sure that the concept was mutually beneficial for all the components.

Figure 1.1

The partnership concept (Ahlström, 2002)

Whilst this concept was not new, through its marketing of the UEFA Champions League (UCL) TEAM has exploited the commercial opportunities in a global marketplace and, with UEFA, has created an integrated sporting and commercial platform for Europe’s elite clubs. In this chapter we focus on the key success factors in transforming the UEFA Champions League into a benchmark global sports brand.

The product: the UEFA Champions League

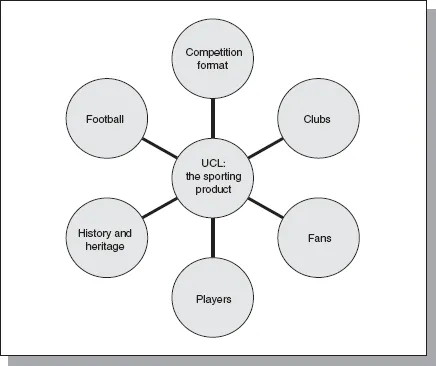

The fundamental factor in the successful transformation of the UCL into a benchmark global brand is the sporting product itself. This consists of a number of crucial interacting elements which blend together to produce a competition with consistently high levels of interest. These elements are illustrated in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2

Facets of the UEFA Champions League product

It is impossible to grade the importance of the various elements of the sporting product individually, as they work together and coalesce to form an effective whole. The roots of the success of the UCL are, of course, grounded in the worldwide popularity of football. Europe is football’s economic centre, and as such attracts star players from across the world. Those star players are employed by the most famous elite clubs, which in turn enjoy remarkable loyalty from their supporters. The clubs are the brands that operate within the UCL brand. As noted above, the UCL is the successor of the European Cup, first played in 1955. It is within that historical context that the UCL exists as the legitimate tournament played to decide Europe’s greatest football teams.

The historical context and the heritage of the competition are at the heart of the UCL branding. As sociologist Anthony King (2004: 331) has argued, ‘tradition is extremely important for the viability of the Champions League. Sports matches have meaning where there is a historical connection which fans and players recognize.’ That meaning therefore exists as a vitally important aspect of the UCL product. Victory in the competition does not exist as a solitary moment of success, but rather as the latest achievement in an ongoing process. This was notable in the recent success of Liverpool in 2005. It was the club’s fifth victory in the competition, the previous of which had been over twenty years previously and to which there was frequent media reference. Similarly, the importance of the players is not confined to the years in which they compete. They are part of a wider historical trajectory, in which the UCL provides the platform and recognition for the game’s greatest talents.

The UCL, then, is subject to the contradictory demands of amalgamating the need for modernization whilst consistently relating the tournament to past events. This is particularly pertinent in the context of the changing format of the competition, which has also helped to facilitate the creation of the global brand. The two key developments were the introduction of a group stage in 1992–93, facilitating a greater number of guaranteed games for clubs, and the opening up of the competition to more than one club from each country in 1997–98. These changes marked a radical departure from a knock-out competition designed purely for national champions. These changes were the subject of much heated debate, and in some quarters were depicted as a betrayal of the European Cup. What the changes achieved, however, was to allow for a greater number of participants and a greater number of games between Europe’s elite clubs. This generated significant extra interest in the major football nations with the largest markets, which in turn has formed the basis of the strategic commercial development of the UCL. Whilst the changes in format have created something of a virtuous circle for the top clubs (participation generates substantial revenue, enabling clubs to consolidate their success in the national leagues), another success factor is that the competition continues to be organized around important sporting and organizational principles:

All the sporting elements, all the competition criteria, have been driven by UEFA without influence from TEAM at all. In the early days the concept was developed by TEAM. It was adapted, and adopted by UEFA to fit their needs, and I think what has happened in the last three or four years, is that it is finessing everything that we do … Both sides would take their credit for having an influence over the parts of the competition that they had the responsibility for. But it’s driven by UEFA and it is supported and implemented by TEAM.

(Richard Worth, Chief Executive, TEAM, personal interview, 1 March 2005.)

At the end of the day we are a sporting governing body. We are not a private entity. Our duty is to the fans, to the European kids, to everybody’s development of football. We’ve got to make sure that we develop it in a way which is appropriate, which is durable for European football … at one point sport should always prevail.

(Philippe Le Floc’h, Director, Marketing and Media Rights, UEFA, personal interview, 19 November 2004.)

UEFA’s control of the sporting format is important. It allows the organization to balance the commercial requirements of the competition with important sporting principles. These include allowing access to the tournament and its rewards to all UEFA’s fifty-two national members, as opposed to just the main markets which generate the vast majority of revenue. This provides an incentive for de...