![]()

1

Introduction

It was in the winter of 1998 when I stumbled upon an online advertisement promising the ‘purely virtual experience’ in a place filled with hundreds of new towns and cities, its thrill compared to the excitement of nineteenth century frontier America, with a citizenship of over 20,000, growing minute by minute. Intrigued, I followed the instructions on the advertisement and waited impatiently for the ‘virtual experience’ to take me by storm. Following my immigration into this virtual space I was prompted with the question ‘who would you like to be today?’. Carefully choosing my name and physical representation, I was donned with my new persona. I first entered a space called the Gateway, a common meeting place for friends, relatives and even lovers who frequented this place. Dozens of animated characters could be found engaged in conversation and exploring the fertile virtual grasslands. Some would enter buildings and scale their virtual heights in elevators, while others could be seen busily rushing around a large space that was cordoned off with tape which bore the inscription ‘vandalised property – under reconstruction’. Moving on to a more secluded area, near what seemed to be the entrance to a shopping mall, I overheard one couple introduce themselves. The scantily clad woman visiting from Spain was commenting how lovely the morning was in Javea, as a young man visiting in the early hours from Phoenix, Arizona, listened impatiently. At first the chat seemed polite, until the boy turned the conversation, aggressively asking personal questions of a sexual nature. Following a few expletives two others arrived in uniform, separating what had become perpetrator and victim. After a few warnings the boy vanished into thin air. Quickly one of the uniformed men exclaimed ‘another one banished, can we please try and keep it civil’. Feeling as if I were intruding on a virtual crime scene I turned to look up to the snow-top covered mountains on the horizon. I noticed pathways leading off into the distance. Intrigued I followed one. At the end I found portals; gateways to other worlds like this one. Fascinated with what I had already seen I donned my explorer’s hat and stepped through.

These were my first experiences of a place called Cyberworlds. It is a social space consisting of a vast array of towns, cities and worlds eclectically populated by over one million citizens and tourists. Its members holistically identify as a ‘community’, evidencing the qualifying characteristics of a shared history, shared language and rituals, a shared virtual geography, universal laws and regulations and a common belief system. Cyberworlds, like almost all other communities, also has a ‘crime’ problem. However, as the name denotes, Cyberworlds does not exist in the ‘terrestrial’ world. It is an elaborate computer program that is distributed over computer networks to all its citizens and tourists. As a result of its ‘virtual’ status the citizens and tourists of Cyberworlds never actually leave the comfort of their homes, schools or offices when visiting. Interaction is performed and relationships are sustained at-a-distance. The Cyberworlds ‘community’ forms the focus of this study; its social structure, ‘crime’ problem and regulatory mechanisms are examined by employing a ‘virtual’ ethnography.1 Analysis focuses upon one ‘virtual’ community in order to better understand how social networks are sustained, how deviance manifests and how social control methods operate within a particular online setting. Where relevant, themes emerging from the data are also applied to the wider Internet context. Acknowledging a paucity in the empirical and theoretical understanding of online deviant activity, this research seeks to deepen and complement the current breadth of knowledge.

Cyberworlds is indicative of what might be termed late-modern forms of communication and interactivity. Increasingly experience is being mediated through networks (Castells 1996). The convenience and convergence of mobile communications and computer-mediated communication has seen terrestrial populations become increasingly dependent upon technology to mediate their everyday practices (Lash 2001). In particular, the Internet and its associated technologies are being employed to facilitate one-to-one and one-to-many communications on a daily basis within the arenas of social, political and economic life. Of particular interest are those groups of people who not only use new forms of technology to mediate their existing ‘real’ lives, but take a further step, using technology to create a new life. Groups of individuals are beginning to flee the physicality of their ‘real’ world, opting instead to take up residence in ‘virtual’ or online social spaces. Citizens and visitors of Cyberworlds, one of a myriad of online social spaces, often report spending over six hours a day within the ‘community’. The proliferation of ‘netizens’ has led commentators to proclaim that the Internet, and the alternative social arena it offers, acts as a ‘new community’ to replace failing social relations in the ‘real’ world (Rheingold 1993). Others have come to perceive it as the new ‘third place’, a communal space, separate from the other spaces of work and home, which individuals frequent in search of solace and friendship (Oldenburg 1999). What is evident is that a new social space has opened up where, for the most part, the constraints of everyday terrestrial life are suspended. Interactivity has taken on a markedly different form and populations are engineering alternative communities with their own social practices, rules, regulations and problems.

The empirical themes covered in this study examine the claims that online community exists in some form, and that online deviance and regulation are intrinsically linked to these online social networks. First the notion of online community is discussed in detail, initially focusing upon academic debate, progressing to an analysis of data gathered from within Cyberworlds. Second, recent debate over the phenomenon of cybercrime is delineated. Data elicited via online focus groups is then analysed to theoretically explore the manifestation and aetiology of deviance within Cyberworlds, deepening our overall understanding of cybercrime more generally.2 How cybercrime and deviance within Cyberworlds are regulated forms the focus of the final empirical theme. The maturation of regulation within Cyberworlds is mapped and is compared and contrasted with wider modes of Internet regulation. Through each empirical theme runs the theoretical underpinnings of the study, focusing on the importance of a bond to online community in preventing deviance (Hirschi 1969) and the hidden power of language to harm online (Butler 1997).

Of the most significant problems facing the Cyberworlds ‘community’, deviant and anti-social behaviour has proved the most arduous to overcome. This is not a unique problem. Cyber deviant phenomena plague all online social spaces. The advent of networked computer technologies has opened up countless deviant and criminal opportunities to both the classical offender and those previously ill-equipped potential offenders. The specific characteristics of the Internet have opened up a new ‘virtual criminal field’ (Capeller 2001). New technologies are both facilitating traditional criminal activities and creating avenues for new and unprecedented forms of deviance, yet to be rationalised in legal discourse. The devolution of computer network access to the domestic arena can be seen as a milestone in cyber criminal and cyber deviant entrepreneurship. During the Cold War, in response to the launch of Sputnik in 1957, the US established the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), the birthplace of what is now commonly known as the Internet. ARPA’s remit was to develop a networked computer infrastructure for use by the military which could survive a nuclear attack. The need to expand the network beyond the military and private sector to universities was quickly realised resulting in the establishment of ARPANET. During the latter years of the 1980s the Internet slowly began to be devolved from the private and university sector to the domestic arena. Since this time the Internet has experienced exponential growth. In 1997 only 2 per cent of the UK’s population had access to the Internet compared to 55 per cent in 2005. Currently 17 per cent of the world’s population have Internet access (CIA 2005).

The pervasiveness of communications technology means that a user no longer needs the esoteric knowledge of a computer programmer to become a cyber criminal. In its infancy cyber criminal activity was the avocation of a small number of computer programmers and others with similar technical expertise. These were the game hackers and crackers of the 1980s (Taylor 2001). The impetus behind cyber criminal activity was usually non-malignant and based on a utopian idealism of non-centralised computer hardware and software access. The illicit activities of these individuals were not widely detected or publicised. During this time law enforcement was far from capable of either proactively or reactively tackling the problem. More accurately, cyber criminal activity was not considered a problem until the mid-1990s. Increasingly there were reports of the misuse of the Internet and similar technologies. Community members, newsgroup members and website owners began to complain of online harassment and defamation, breaches of decency due to the online dissemination of ‘obscene’ materials, instances of vandalised web pages, and even cases of ‘virtual rape’ (MacKinnon 1997b). A clear shift occurred from the relatively benign cyber deviant activity of the 1980s to the malicious cyber criminal activity of the mid- to late 1990s. The problem has been perceived to be so acute that governments are establishing contingency plans in the event of cyber-terrorist attacks, and are creating specialised law enforcement agencies to tackle cyber criminal phenomena (Jewkes 2003). Due to the moral panic that has recently arisen around dangerous sex offenders and their use of the Internet, the domestic arena, particularly parents, have been targeted with ‘cyber safety’ advertisement campaigns, highlighting the ‘darker side’ to the Internet. What was once touted as cyber utopia has become tainted by misuse and misfortune.

However, to state that the Internet is a dangerous and unruly place is mistaken. While its features have allowed individuals to access illegal material and to defame others, a hierarchy of social control is firmly entrenched and can often redress many of the wrongs done (Wall 2001). Rules, regulations, values and beliefs are evident in almost all online ‘communities’, including newsgroups and Internet Relay Chat. More systematically Internet Service Providers (ISPs), who supply the Internet to domestic users, have their own codes of good practice when using the technology. Via a slow process, bodies of law have been adapted to include certain cyber activities as criminal. At the supranational level conventions have been established in an attempt to regulate what has become the global problem of cybercrime. What exists then is a highly ordered structure of governance (Wall 2001).

Formal offline regulatory mechanisms, along with the taxonomy of cyber criminal activity, have received some detailed academic attention (see Akdeniz et al. 2000; Grabosky and Smith 1998; Taylor 1999; and Wall 2001 for an overview). However, little research has examined the ways in which online ‘communities’ govern themselves or the nature and extent of the deviant acts that plague their citizens. There is much to be learnt about online ‘community’, social control and regulation from the netizens that were integral to its creation and maturation. Understanding these ‘native’ processes is essential to the development of more general regulatory practice, beyond individual online communities. Similarly, while our understanding of ‘conventional’ cybercrimes is quite extensive, little knowledge exists on the more indigenous forms of deviant activity that infest online communities. While we understand how new technologies have facilitated certain crimes, such as theft, we understand less the ways in which the same technologies have created new avenues for deviant enterprise, such as ‘virtual vandalism’ and ‘virtual rape’. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap by exploring the online indigenous forms of ‘community’, social control and deviant activity.

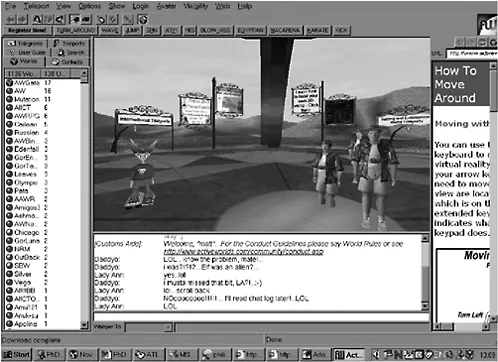

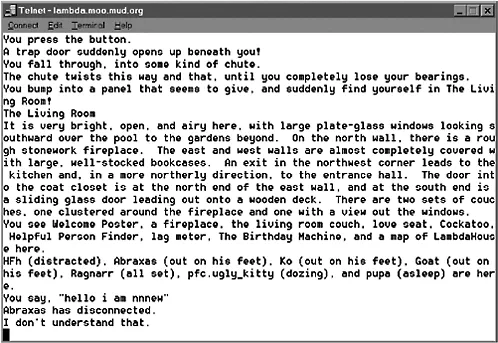

The site of inquiry

Cyberworlds is one of a handful of graphically represented three-dimensional virtual reality online social spaces that forms part of the Internet (see Figure 1.1). These online arenas can be described as second generation Multi-User Domains (MUDs); less technologically advanced methods of one-to-many text-only online communication first developed in the late 1970s3 (see Figure 1.2). MUDs were first designed by programmers as gaming arenas, much like an online version of the classic role playing game ‘Dungeons and Dragons’. In traditional MUDs, action, description and communication take place purely through text. Users have to rely on their imagination to create the environment that is being described to them. Cyberworlds takes advantage of broadband network communications, meaning much more information can be transmitted in shorter periods of time. This allows for information to be represented by more that just simple text. A graphical window allows a user to see themselves represented as an avatar, a three-dimensional persona. Via this interface users can locate each other and navigate around their three-dimensional environment. Text still functions as communication, and is essential to the maintenance of the ‘community’, but it has become relegated where visual components now represent action and description. Cyberworlds and other ‘advanced’ MUDs have grown in popularity over the last decade due to the level of social and ‘physical’ immersion they provide to the user. Essentially they are the closest domestic technology to more elaborate and expensive Virtual Reality (VR) platforms.

Over decades, as increasing numbers of people became connected to computer networks, gaming spaces transformed into more general social spaces, providing an escape from the terrestrial world. MUDs and the social networks they harbour have been the subject of much research in media and communications disciplines (see Jones 1995, 1997, 1998 for an overview). Many studies have focused upon the substantive issues of race, gender and sexuality within MUDs and other associated technologies (such as newsgroups and Internet Relay Chat). The effects of anonymity and disembodiment, experienced by each MUD user, have forged much of what is now understood of online social experience (see Kramarae 1998; Danet 1998; Poster 1998; Dietrich 1997; Shaw 1997). However, graphical MUDs, like Cyberworlds, have received little academic attention. Further, few studies have attempted to empirically examine the phenomena known as cybercrime or cyber deviance within these social settings.

Broadly this study takes Cyberworlds as a site of analysis to ethnographically explore the emergence and maturation of online ‘community’, deviance4 and regulation and to examine how each is interrelated. In its constituent parts the study focuses on three aspects of the Cyberworlds community, which translate into the four areas of inquiry. The first focuses upon the question of Cyberworlds as a ‘social’ space; essentially the characteristics of its social networks and the extent to which it can be said to be a ‘community’. Second, focus shifts to an examination of how deviant and anti-social activity manifest within Cyberworlds, and how the existence or absence of a bond to community relates to its aetiology. Third, how deviant activities are textually performed within general Internet social spaces and Cyberworlds specifically and their capacity to harm are subject to analysis. Finally, the history and effectiveness of the mechanisms put in place to curtail deviant and anti-social activity within Cyberworlds are examined. The subsequent discussion applies these key themes to the wider Internet space more generally.

Overview

The second chapter provides a context within which the st...