1

Understanding Television Today

Locating television

Towards the end of our Introduction, we suggested that television studies may actually know less about the consumption of television and its role in every- day life today than it did during the ‘broadcast era’.1 That may seem like a slightly surprising statement, given the level of activity in publishing and research on television and new media over the last decade or so. Debate about the functions and futures of new technologies, new platforms, new global trade economies, and new sites of production has been vigorous and extensive. Much of this work, however, has been dominated by consideration of the possible or likely futures of television rather than by detailed examinations of present practices around television.

What we mean to highlight through that comment is the disparity between the confidence that accompanied cultural studies’ accounts of the relation between television and culture in such key texts of the 1980s as John Fiske’s Television Culture ( Fiske 1987 ) or Ien Ang’s Watching Dallas ( Ang 1985 ), and the confidence we might have in the authority and comprehensiveness of more contemporary accounts. As we noted in the Introduction, both the industrial and the academic context for these accounts have seen dramatic changes. The earlier texts addressed a relatively standardized environment in which broadcasting reigned supreme, network schedules gathered a mass audience nightly and regulatory structures positioned television as a national system. As a result, the pioneers of television studies assumed, perhaps legitimately, a general applicability for much of what they said about television within the English- speaking world and across most of the West. Hence, the clustering of debates about television audiences which focused on the formation of the citizen, the construction of consensus or variations on the model of the ‘bardic function’ of television as the voice of a largely national community. At roughly the same time, early anthropological accounts of television’s introduction into groups that had previously only loosely identified with national communities approached televi- sion from a complementary nationalist focus –such as in Kottak’s ground- breaking 19892 study of television in rural Brazil. Such literature suggested that television’s potential to create national communities in newly formed nations, or to bring marginal groups into developing nations, could be as powerful outside the West as within it ( Kottak 2009 ; Foster 2002 ).

The situation and the debates are significantly different now; it is undeniable that there have been major and widespread shifts in what is variously described as the post-broadcast, post-network, multichannel or post-digital environment.Some of these shifts have been so dramatic, and their possible implications so interesting, that contemporary scholarship has been dominated by the task of coming to terms with them. Much of the resulting work, however, is relatively unrefiective about the highly contingent and diverse character and effects of these changes in different locations. In particular, there has been a marked con- centration upon the US environment –both because it is the default location for analysis by US American scholars and because it has been (in our view, mistakenly) assumed as a likely model for the evolution of television elsewhere.3 As a result, there is still a great deal for contemporary television studies to learn about what is actually happening elsewhere.

That said, it is important to acknowledge that, of course, we do know quite a lot about certain aspects of television today: in particular, research, debate and analysis has concentrated on mapping the changing technologies, and the shifts in programme content, format and provision as the multichannel environment developed, expanded and, unevenly, globalized. In terms of mapping the changes in technology, there is now an enormous literature on the digital, on new media, and on television’s convergence with the online environment. Much of this work is necessarily and usefully descriptive, as it struggles to keep up with an industry which is mutating and innovating at an extraordinary pace. Some of it is also highly speculative. A relatively common strategy in both the academic literature and in media commentary is to draw on particular instances of new media’s take-up in order to predict what kinds of futures this new development might generate right across the media. There are limits to what such a strategy can tell us. Nonetheless, the interest in new possibilities has helped to open up new areas of exploration. The attention paid to the prolifera- tion of digital platforms of delivery has contributed to a climate which is very receptive to new work on the industrial and commercial structures behind these emerging platforms. The writing of political economies of global media has been revitalized through such studies as Michael Curtin’s work on ‘media capitals’>( Curtin 2004 ) and on the emergence of the Chinese market for television (Curtin 2007). There is a relation between this kind of interest and the new forms of critical industry analysis developed by, among others, Tim Havens, Amanda Lotz and Serra Tinic (Havens et al. 2009). Furthermore, while we might be sceptical about the actual scale and provenance of the much-vaunted blurring of the consumption/production divide enabled by digital media ( Bruns 2008 ; Hartley 2009), that development has contributed to a new burst of interest in studying the mutating processes of production for television and its related platforms, which has in turn contributed to a climate in which the relatively new enterprise of production studies ( Caldwell 2008 ; Mayer et al. 2009a) has prospered.

Slightly less infiuential than the ‘digital turn’, so far, but still worth noting, is the ongoing internationalization of television studies. Dating back to at least the beginning of this century, there has been a steady growth in the amount of published work in English that deals with non-Western media in general (Curran and Park 2000; Thussu 2007), and television has been a major part of that development. Much of the resulting discussion has dealt with particular programming formats –reality TV in particular –but there has also been a significant increase in the resources available to those interested in a more comparative transnational view of the contemporary state of television. Work on Asian and Arab television ( Thomas 2005 ; Keane et al. 2007; Sakr 2007 ; Kraidy and Khalil 2009), for instance, has been particularly useful in troubling some of the master narratives in Western cultural, media and television studies mentioned in our Introduction. As we will discuss later in this chapter, from the 1980s onwards parallel developments were occurring in anthropology as that discipline became consumed, and to some degree transformed, by an increasing necessity to come to terms with theorizing culture in contexts that included an array of mass media forms.

There is reason to believe that the emphasis upon studying the new platforms for delivery, on the one hand, and recent transnational trends in programming and formats, on the other, has resulted in a certain de-contextualization, perhaps even a de-territorialization, of television: disconnecting it from the specific locations and communities in which it functions. This may not be too much of a problem for those wanting to focus on shifts in technology, nor perhaps for those who are interested primarily in examining a particular genre of television texts, but it does constrain our capacity to talk about what television does as a sociocultural form, as a cultural institution, as a material object and as a multi- faceted component of our everyday domestic lives. Talking about these aspects of what television does, a conversation that was for many years effectively the default setting for television studies is now less common because it is now much more difficult. For instance, the extent to which television, in many locations, has mutated in ways that no longer make it entirely appropriate to think of it as a national institution, plays an important role in increasing the degree of difficulty. As a result, as Charlotte Brunsdon has said,

it is much less clear what stories will be told about television, what contexts are relevant and how we should interpret and understand its own stories, when those constitutive connections between medium and nation are more attenuated, when the noise has been stripped away, and the stories have been repackaged to travel the world.

( Brunsdon 2010 : 73)

Television studies is still in the process of responding to this situation as it transitions from the broadcast era to a much more complicated present.

Brunsdon’s comment reminds us that one of the things that television’s institutional origins did was to thoroughly anchor the medium in its location, necessitating close attention to the rationales used to justify the nation’s investment in television’s definition, development, industrial structure and regulation. Such rationales were based on specific claims about television’s social and cultural function, as well as the proposition of its importance as a part of the nation-state’s communications and information infrastructure. Deregulation, commercialization and a redefinition of television that emphasized its function as a medium of entertainment have combined with the massive expansion of provision in many locations to pull up this anchor. Where this has occurred (and there is still much work to be done to establish just how widespread this pattern actually is), questions about television’s location and sociocultural function have become less prominent. Nonetheless, the argument we make in this book is that the question of location remains fundamental.

This is not only in relation to the project of understanding television today, but it is increasingly evident in the concerns that have infiuenced the theore- tical development of a number of humanities and social science disciplines. The theorization of space and place is one of the growth areas in cultural studies, cultural geography, anthropology and sociology in recent years. Among the earliest to apply these developments to the examination of the media is David Morley’s Home Territories (Morley 2000), which took up the challenge of properly investigating, through media, what had happened to the idea of the home in the era of postmodernity when so much attention was focused on forms of mobility. We are entirely sympathetic to his response to that challenge:

If the transformations in communications and transport networks char- acteristic of our period, involving various forms of mediation, displacement and de-territorialization are generally held to have transformed our sense of place, their theorization has often proceeded at a highly abstract level, towards a generalized account of nomadology. Recent critiques of the ‘EurAmcentric’ nature of most postmodern theory point to the dangers of such inappropriately universalized frameworks of analysis. My aim here is to open up the analysis of the varieties of rootedness, exile, diaspora, dis- placement, connectedness and/or mobility, experienced by members of groups in a range of socio-geographical positions.

(3)

Morley goes on to ground his examination of national and transnational iden- tities in the domestic micro-processes through which ‘the smaller units which make up that larger community [i.e. the nation] are themselves constituted’. He argues that ‘the articulation of the domestic household into the “symbolic family ” of the nation (or wider group) can best be understood by focusing on the role of media and communications technologies’ (3). In his study, then, the home and the family (variously defined) provide the starting points for examining both the construction of place and the function of the media. Morley’s study remains relatively unusual, even though Elanda Levine has recently suggested that ‘as scholars of media and culture continue to explore the significance of place, of geographies –both virtual and actual –of communities and identities in a globalized world, questions of location have become increasingly significant to media studies’ ( Levine 2009 : 154). We agree that questions of location are of fundamental importance, but we would suggest that they are still minor considerations in most accounts of television today.

In the opening chapter of his edited collection, Re-Locating Television: Television in the Digital Context , Jostein Gripsrud (2010a) presents one response to this situation. While recognizing that there is no longer an agreed basis for understanding the political, social and cultural role of television today, Gripsrud’s collection investigates some options for generating that under- standing. Resisting the more speculative possibilities advanced by the digital media enthusiasts, while nonetheless acknowledging the significance of the changes that are continuing to occur, Gripsrud argues that there is still a point to thinking about how even a thoroughly transformed television might be located within the public sphere. It would be a very different public sphere, though, to the one we experienced under an earlier formation of the media. In the truly multichannel markets, television viewers are spread across hundreds of channels, while also watching TV off-schedule through time-shifting technologies; in such a context, even where there are large audiences, they are not necessarily experiencing anything like old-fashioned ‘mass’ consumption. Although, Gripsrud acknowledges, this may be a problem for advertisers,

it may be less of a problem for those whose primary interest is to maintain a functioning public sphere, towards which all weak publics and all subaltern counterpublics gravitate in order to effectively critique or infiuence decisions affectting all society.

(21)

Even when an expanded menu of choices is available, Gripsrud argues that, in practice, the audience is not quite so diverse, nor their choices so numerous, as the expanded provision might imply. As has been repeatedly demonstrated, audiences ‘flock regularly to a quite limited number of channels’, but ‘only rarely visit the many dozens of others’ (21). Drawing on a comparison with the diverse national publics which make up the European community, he argues that even within that context there is a political and discursive space in which an ensemble of publics can discuss common concerns within ‘a shared frame of relevance’ (21). Similarly, he says, ‘the coherence of multi-channel national public spheres, in multi-ethnic societies, can arguably be maintained along similar lines’. Downplaying the dangers of what Sunstein describes as ‘cyber- balkanization’ –the accelerating fragmentation of online publics –Gripsrud argues that there are grounds for some confidence in the ‘continued existence of a relatively centralized and uniting broadcast television system … together with a degree of centralization on the internet’ (21).

Gripsrud has been consistently sceptical about the apocalyptic predictions that come from those who see the digital era ‘changing everything’ ( Shirky 2008 ). Also, he has been an advocate of what is effectively the public service mission of the media ( Gripsrud 2004 ), the core benefits of the broadcast era: universal, free access to information and to a public conversation. In this essay, though, he also acknowledges that the effective functioning of the public sphere depends on much more than simply the provision of an accessible television service. He refers to Couldry, Livingstone and Markham’s research on ‘public connection’ (Couldry et al. 2007), a large study which maps its subjects’ media consumption against their engagement with public social and political issues, and which finds a ‘weakening connection’ to the political public sphere:

On the basis of national empirical research, Nick Couldry, Sonia Living- stone and Tim Markham (2007) have expressed concern about a lack of ‘public connection’>in an increasing proportion of the population. Public connection is the minimal precondition of at least periodical attention to what goes on in the central processes of democracy, in the political public sphere. There are many signs that such a connection may be lacking among increasing numbers of people in the Western world.

(22)

To understand this requires more than just an examination of the media. Accordingly, Gripsrud suggests that what is needed to

grasp the real significance of today’s media developments, with a view to the functioning of a democratic public sphere, is to start by situating ourselves and our media within a wider socio-historical context and study our chosen area of special interest against that background.

(23)

To some extent, the essays which make up the rest of his collection respond to that suggestion but overall they still conform to the dominant patterns of approaches and interests we described at the beginning of this chapter. Gripsrud’s proposal for rethinking how television might be located within a diversifying post- digital public sphere is important, however, and remains an active question for the future agenda of television studies.

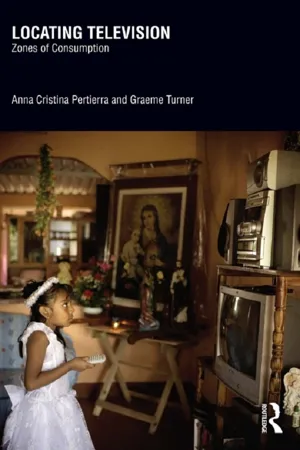

While our titles may seem similar, our project in this book differs significantly from that which motivates Re-Locating Television. The location Gripsrud addresses is a public media space –what he talks of as a public sphere –whereas we are also looking at actual physical places. At the broadest level these are spaces that are geo-politically and physically defined but they are not necessarily nation-states: the home, the locality or the region may be just as relevant as a means of delineating the location we wish to examine. Our approach emphasizes the necessity, though, of locating television within particular political, cultural, historical or geographic spaces. The point of using a notion such as ‘zones of consumption’ is to recognize that the actual construction of the location within which the consumption of television occurs is itself contingent, conjunctural and instantiated.

Our emphasis on consumption constitutes another difference between the approach taken in this book and that taken in Grisprud’s collection. We argue that the uses of television and new media need to be understood within the structure of everyday life. Not only does this involve attention to the domestic micro-processes of habit and behaviour that make up our performance of every- day life, but it also involves, for instance, considering television as a component of material culture as well as a medium of representation. Also, in Chapter 4, we locate the consumption of television within what, following Silverstone, Hirsch and Morley (1992), we describe as the domestic moral economy –the rules and structures and understandings that regulate and organize domestic life. In our view, these are important dimensions of experience that are missing from the dominant concerns of contemporary television studies but which are highlighted by a ‘non-mediacentric form of media studies’; the result is a better understanding of ‘the variety of ways in which old and new media accommodate to each other and coexist in symbolic forms and also how … we live...