Chapter 1

An introduction to classroom observation

Purposes and uses of observation

The elements of the classroom

Different methods of observation

The observer

Recording the observation

‘What sort of classroom observation shall we do?’ This question is increasingly asked, when research into teaching and learning is undertaken, but it is also an issue discussed before the appraisal of experienced teachers, the training of novices or the inspection of schools. Nor is it only an issue for professional people. Parents, for example, may be invited into schools to see some teaching, as many schools have open days when visitors can watch what is happening in lessons. Classrooms are still relatively private places, but they are more open to scrutiny than they used to be. A great deal of money is spent on educating the next gener-ation of citizens, consequently many people have a right to know what is going on in classrooms, where so much important teaching and learning takes place, even though children may learn from a variety of other sources.

Classrooms are exceptionally busy places, so observers need to be on their toes. Every day in classrooms around the world billions of events take place: teachers ask children questions, new concepts are explained, pupils talk to each other, some of those who misbehave are reprimanded, others are ignored. Jackson (1968) reported a study in which it was found that primary teachers engaged in as many as 1,000 such interpersonal exchanges in a single day. This means, if the pattern is repeated, 5,000 in a week, 200,000 in a year, millions in a professional career. In another study of videotapes by Adams and Biddle (1970), there was a change in ‘activity’ every 5–18 seconds and there was an average in each lesson of 174 changes in who talked and who listened. The job of teaching can be as busy as that of a telephonist or a sales assistant during peak shopping hours.

Yet despite greater openness to scrutiny, in many classrooms the craft of teaching is still largely a private affair. Some teachers spend 40 years in the classroom, teaching maybe 50,000 lessons or more, of which only a tiny number are witnessed by other adults. It is often difficult to obtain detailed accounts of lessons, because teachers are so busy with the running of the lesson there is little time for them to make notes or photographic records. I once went to a rural primary school and observed some of the most exciting science work I have ever seen. When I urged the teacher to write up what he was doing so that others could read about it, he declined, saying that his colleagues might think he was boasting. By contrast practice in surgery is a much more open matter. The developers of transplant and bypass surgery took it for granted that successful new techniques must be witnessed by and disseminated to others, through their actual presence at operations, or by means of videotapes and the written and spoken word.

Classroom observation is now becoming far more common than it once was. The advent of systematic teacher appraisal and lesson evaluation, the greater emphasis on developing the professional skills of initial trainees, or honing those of experienced practitioners, the increased interest in classroom processes by curriculum developers, all of these have led to more scrutiny of what actually goes on during teaching and learning. It is much more likely now, compared to the mid-1970s or even the mid-1980s, that one person will sit in and observe the lessons of another as part of a teacher appraisal exercise, or that a teacher supervising a student will be expected to make a more detailed analysis of lessons observed than might once have been the case.

If lessons are worth observing then they are also worth analysing properly, for little purpose is served if, after a lesson, observers simply exude goodwill, mumble vaguely or appear to be uncertain why they are there, or what they should talk about. The purpose of this book, therefore, is to describe the many contexts in which lessons are observed, discuss the purposes and outcomes of observation, the different approaches to lesson analysis, and the uses that can be made of the careful scrutiny of classroom events. There is now a huge constituency of people who need to be aware of what is involved in lesson observation or how it might be conducted. These include teachers, heads, student teachers, inspectors, appraisers, researchers, curriculum developers and anyone else who ever sits in on a lesson with a serious purpose. Skilfully handled classroom observation can benefit both the observer and the person observed, serving to inform and enhance the professional skill of both people. Badly handled, however, it becomes counterproductive, at its worst arousing hostility, resistance and suspicion.

Purposes and uses of observation

Consider just a few of the many uses of classroom observation: a primary teacher is being observed by the school’s language co-ordinator, who comes for the morning to look at what can be done in response to concern about the relatively low literacy levels of certain boys in the school; a secondary science teacher is watched by the head of department during a one and a half hour laboratory session as part of the science department’s self-appraisal exercise; a student on teaching practice is seen by a supervising teacher or tutor; a maths lesson is scrutinized by an inspector during a formal inspection of the school; a class of 7 year olds is observed by a teacher who is also a textbook writer preparing a series of mathematics activities for young children; a researcher studying teachers’ questioning techniques watches a secondary geography class, noting down the various questions asked by the teacher and the responses obtained.

All of these are watching lessons, yet their purposes and approaches are very diverse. The mathematics textbook writer might focus specifically on individual pupils to see how effectively they coped with different kinds of activities, whereas the appraisers might give much of their time to the teacher’s questioning, explaining, class management, the nature of the tasks set, and pupils’ learning. One might make detailed notes, take photographs and record the whole process on video. Another might write little down, but rather reflect on what could be discussed with the teacher later.

What is important in all these cases is that the methods of classroom observation should suit its purposes. There is little point, when observing a student teacher, for example, in employing all the paraphernalia of a detailed research project if a different structure would make more sense. The research project might be using extensive systematic observation of pupils’ movements, whereas the student might be having class management problems, so the principal focus might be on why children appear to be misbehaving, what they actually do, how the teacher responds, and what might be altered in future to avoid disruptive behaviour. The observer might, therefore, concentrate on the tasks the children have been set or devised for themselves, incidents that reveal the relationships between teacher and pupils and among the pupils themselves, the nature of classroom rules, or the lack of them. The purpose, timing and context of an observation should largely determine its methods, and this book describes how a range of approaches can be employed to meet a variety of needs.

ACTIVITY 1

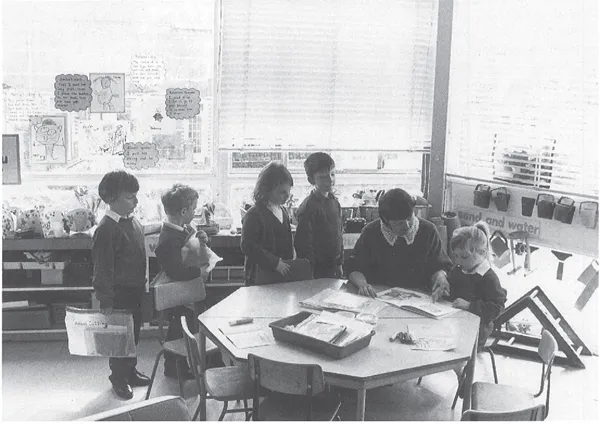

Look at the photograph (Figure 1.1). Imagine that the teacher is concerned that she always seems to be trapped at her desk, with about a third of the class, sometimes as many as a half, waiting in line to see her. Consider how you might analyse what is happening, what would be the focus of your observations, the nature of the written record you might keep of events and what you might discuss afterwards.

There are many points on which to focus in such circumstances. Sometimes the teacher has made the pupils too dependent on her, and may simply want to know how to spell words, when they might easily use a dictionary. The observer might look for examples of dependency so that these could be discussed later.

Figure 1.1 Children queuing at teacher’s desk

The elements of the classroom

One of the problems faced by both experienced and inexperienced classroom observers is the matter of deciding what should be the focus of attention. So much happens in classrooms that any task or event, even apparently simple ones, could be the subject of pages of notes and hours of discussion. The ecology of many classrooms can be extremely rich and full. The main constituents of them are teachers, pupils, buildings and materials.

Teachers are the paid professionals, expected in law to act as a thoughtful parent might, to be in loco parentis. In order to fulfil what the law calls the ‘duty of care’, therefore, teachers are given certain powers as well as responsibilities. They may from time to time, for example, give punishments to children who do not behave properly, or take action to prevent injury to a pupil. Teachers’ own background, personality, interests, knowledge, intentions and preferences will influence much of what occurs, such as the strategies they employ in different situations, the timing and nature of their questions and explanations, their responses to misbehaviour, indeed what they perceive to be deviant behaviour.

During any one day teachers may fill a variety of roles in carrying out their duties. These can include not only the traditional one of transmitter of knowledge, but also others such as counsellor (advising pupils about careers, aspirations or problems), social worker (dealing with family issues), assessor (marking children’s work, giving tests, writing reports), manager (looking after resources, organising groups, setting goals), even jailer (keeping in school reluctant attenders or checking up on possible truants). As classroom life can be busy and rapidly changing, some teachers may fulfil several of these roles within the same lesson.

Children may also play different roles during lessons, sometimes in accordance with what is expected and required by the teacher, on other occasions according to their own choice. They are expected to be learners of knowledge, skills, attitudes or behaviour. From time to time they may also be deviants (misbehaving, not doing what the teacher has asked), jokers (laughing, creating humour which may lighten or heighten tension), collaborators (working closely with others as members of a team or group), investigators (enquiring, problem solving, exploring, testing hypotheses) or even servants (moving furniture, carrying and setting up equipment). As was the case with teachers, their background, personality, interests, prior knowledge, intentions and preferences will influence much of what occurs. Furthermore they will often be conscious of other members of their peer group, especially in ado-lescence, and this too will sometimes form a powerful influence on what they do.

Teaching takes place in a huge variety of locations. In institutions like schools and colleges, there are usually box-shaped classrooms, with furniture arranged in rows or around tables. This may not be the case in subjects like physical education or dance, however, where learning may take place in an open space or outdoors. Nor is it necessarily the norm in adult education, which may be located in the factory, the retail shop or even in settings like clubs, hospitals and people’s homes, where there may be considerable informality. Open plan areas in schools may be L-shaped, circular or constructed with some quite irreg-ular arrangement of space. We may well, on relatively rare occasions, be able to sit down with architects when designing a new school and try to turn our aspirations into reality, but most teachers have been given little say over the classrooms in which they teach and may find the buildings influence the styles of teaching that are possible, rather than the other way round.

Even within the same building there may be different uses of the spaces available. Teacher A may have a room with desks laid out in rows, teacher B may prefer groups working around tables, and teacher C may do so much practical work and movement that neither of these arrangements is appropriate. One primary age child may spend each day as a member of a large group of eighty pupils of similar age in a three class open plan area, another may be in a small village school built in the nineteenth century with twenty pupils of different ages. All these ecological factors, some beyond the direct control of teacher or pupil, can affect the nature of classroom interaction.

When it comes to the materials which children and teachers use, the books and equipment, the same variety can be noted. Herbert (1967) spent two years studying a school which had been specially designed for team teaching; he found that the learning media being used included eleven forms of book and printed matter (e.g. textbooks, worksheets, periodicals), nine forms of reference book (dictionary, encyclopedia, atlas, almanac), five kinds of test (textbook test, teacher-made test, standardised test), nine sorts of contentless media (paper, paint, crayon, clay), eleven forms of flat graphics (charts, posters, diagrams, magnetic boards), nine types of three-dimensional media (globes, models, toys, mobiles) and thirteen kinds of visual or audio-visual equipment (overhead projector, slide viewer, television monitor, micro-projector). Nowadays he would have found even more additions, such as computers, word pr...