eBook - ePub

A Guide to Practitioner Research in Education

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Guide to Practitioner Research in Education

About this book

This book is a guide to research methods for practitioner research. Written in friendly and accessible language, it includes numerous practical examples based on the authors? own experiences in the field, to support readers.

The authors provide information and guidance on developing research skills such as gathering and analysing information and data, reporting findings and research design. They offer critical perspectives to help users reflect on research approaches and to scrutinise key issues in devising research questions.

This book is for undergraduate and postgraduate students, teachers and practitioners in practitioner research development and leadership programmes.

The team of authors are all within the School of Education at the University

of Glasgow and have significant experience of working with practitioner

researchers in education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Guide to Practitioner Research in Education by Ian Menter,Dely Elliot,Moira Hulme,Jon Lewin,Kevin Lowden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

What is Research and

Why Do It?

1

What is Research?

In this chapter we discuss what is meant by research, particularly in education. We examine the idea of ‘practitioner research’ and what it might mean for teachers, lecturers and other education professionals. This chapter introduces you to some of the key terms that will be used later in the book and gives you a sense of how best to make use of the book for your own setting.

Research, education and practitioner research

The word ‘research’ carries many meanings and can produce strong reactions.

‘Research is just a load of theory.’

‘I’d like to research this properly but I really don’t have the time.’

‘I’m an experienced teacher and I know what works in my classroom –

I don’t think research can do anything for me.’

‘I’d like to research this properly but I really don’t have the time.’

‘I’m an experienced teacher and I know what works in my classroom –

I don’t think research can do anything for me.’

These are some of the statements we have heard over many years of working with teachers, statements – even though they may sound negative – which have always led to very fruitful discussions.

In this book, where we set out to provide support, encouragement, advice and even inspiration to education practitioners in developing a research dimension to their work, we are hoping to dispel some of the more worrying misrepresentations of research and its application in educational settings.

It is certainly true that research can be defined in many different ways – each dictionary offers a different slant on the term.

A detailed study of a subject, especially in order to discover (new) information or reach a (new) understanding. Cambridge Advanced Learner’s On-line Dictionary

Endeavour to discover new or collate old facts etc. by scientific study of a subject, course of critical investigation. Oxford English Dictionary

Careful, systematic, patient study and investigation in some field of knowledge, undertaken to discover or establish facts or principles. yourdictionary.com

In fact, there is very little agreement between these three – two emphasise finding something new, but the third indicates it can be about ‘establishing’ facts, that are perhaps already known, that is, confirming knowledge rather than discovering something original. Just one mentions scientific study. Between them they suggest the purpose is to find, variously: information, understanding; facts; facts or principles.

When we have asked teachers or student teachers to say what they think the word ‘research’ means, they do often mention words like investigation, data, surveys or theory. The way in which we wish to define research at the outset of this book is, we hope you will agree, relatively simple and will help as a reminder of three key elements in undertaking research in educational settings:

Research is systematic enquiry, the outcomes of which are made available to others.

The three elements to this are:

- Enquiry – this can be taken to mean ‘finding out’ or ‘investigating’, trying to develop some new knowledge and understanding.

- Systematic – for enquiry to be considered to be research, it is necessary that there is some order to the nature of the enquiry, that it has a rationale and an approach which can be explained and defended.

- Sharing outcomes – the form in which the outcomes are disseminated may vary enormously, but the key point being made here is that, if it is only the researcher her/himself who is aware of the outcomes of the research, then the significance of the activity is very limited and may be better described as a form of reflection or personal enquiry, rather than research.

If one puts this general definition of research into the educational context for practitioners, one can elaborate it slightly by saying:

Practitioner research in education is systematic enquiry in an educational setting carried out by someone working in that setting, the outcomes of which are shared with other practitioners.

The additional elements of this definition are:

- The qualifier ‘practitioner research’. This is taken to mean that the person or persons undertaking the research are both researching and practising, very often they are ‘teacher researchers’. It is usually assumed that the research is being undertaken within the practitioner’s own practice, although collaborative practitioner research may suggest a group of teacher researchers working together, investigating practice across a school or college or other educational setting.

- The phrase ‘in educational settings’. As implied above, this is usually taken to be a reference to classrooms, but at this stage it would be desirable to keep a fairly open view about its meaning. It could be interpreted, for example, to include activities in staff rooms, or enquiries with parents or other community members, or indeed to look into the practice of education policy-making, perhaps in local authorities or in government departments.

- Outcomes to be shared with other practitioners. This relates primarily to the purposes of practitioner research. It is usually, perhaps almost always, the case, that those undertaking practitioner research are seeking to develop and improve their own practice. But this definition reminds us that it should be possible, indeed desirable, for others to benefit from hearing about and responding to the research that has been undertaken.

In this book we explore all of these themes in more detail and look at some of the challenges, opportunities and benefits that may be derived from practitioner research in education.

The term ‘evaluation’ is often used in educational settings and it is worth considering what the similarities and differences between research and evaluation may be. There is clearly a significant overlap between the terms and indeed many practitioners feel much more comfortable with ‘evaluation’, which they may see as an integral part of teaching, than they do with ‘research’, which they may see as an additional activity that somehow goes beyond teaching. Similarly, the term ‘reflective teaching’ has become very influential in professional discussions over recent years. In some ways this term has been used as a way of promoting an enquiring approach as an integral part of teaching, rather than imposing some sort of additional burden on teachers.

The term ‘evaluation’ in teaching is commonly used to describe a process through which teachers assess the effectiveness of what they have been doing in the classroom. Following a lesson or series of lessons we might be asking ourselves questions such as:

- What did the pupils/students learn?

- Did the methods that I used for teaching them work well?

- How might I improve my teaching next time?

Such questions can be applied in a simple or in a more complex way. So, ‘What did the pupils learn?’ may be answered simply by observing pupils’ responses during the lesson, or by administering a test or other assessment procedure or by a more detailed investigation. The question about teaching methods implies other questions, such as ‘What alternative teaching methods might I have used?’ and ‘How could I know whether they would be better or not without actually trying them?’

‘Reflective teaching’ is a term that certainly incorporates an idea of evaluation, but in most definitions is seeking to encourage an even more questioning approach. Typically, it involves teachers asking themselves some deeper questions, involving values. In other words as well as the kinds of questions listed above, we may also be asking ourselves:

- What is it important that these pupils/students should be learning?

- Is the way I am teaching consistent with my beliefs about learning and about the rights of pupils/students?

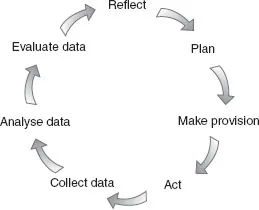

Such an orientation engages with the purposes of education and with explicit statements of values, as well as questions of effectiveness and efficiency/efficacy. Reflective teaching is often depicted as a cyclical process, as represented in Figure 1.1.

Among the principles which underlie reflective teaching, according to Pollard and Tann (1993; from whom Figure 1.1 has been adapted) are:

Reflective teaching implies an active concern with aims and consequences as well as means and practical competence.

Reflective teaching requires competence in methods of classroom enquiry, to support the development of teaching competence.

Figure 1.1 The reflective teaching cycle (adapted from Pollard and Tann, 1993)

Reflective teaching has been a very important concept in initial teacher education and evidence of its influence can be seen both in statements of standards for entry into teaching (especially in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland), and in the introduction of Master’s-level work into teacher education courses. However, it is not only in initial teacher education that a reflective approach has become an important element. Increasingly, the professional development of serving teachers and lecturers has also been informed by these ideas. In many countries recent developments in continuing professional development (CPD) have explicitly called for teachers to reflect upon and learn from their practice. A number of research studies have shown how teacher development can be much more powerful when it is based on teachers’ own practices (see Day, 1999; Reeves and Fox, 2008). Furthermore, a number of formal CPD schemes have demonstrated the effectiveness of such approaches. Examples in England would include the National Professional Qualification for Headteachers (NPQH), or in Scotland the Chartered Teacher Programme or the Scottish Qualification for Headship (SQH). It may also be that the development of the Master’s in Teaching and Learning (MTL) in England will be based on similar approaches.

If we revisit the term ‘practitioner research’ in the light of these two other concepts, we can certainly say that evaluation and reflective teaching are deeply bound into practitioner research, but we might also suggest that there is more to it than either of those terms implies. The term ‘teacher as researcher’ emerged very much from the work of Lawrence Stenhouse in the 1960s and 1970s at a time, at least in England, when teachers played a much greater part in curriculum development than they did in the later part of the twentieth century. In his classic text, An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development, published in 1975, Stenhouse sets out in some detail, a model of teacher as researcher. This model is based on a situation in which the teacher her/himself has considerable scope for determining aspects of the curriculum and considerable autonomy in deciding on pedagogical approaches to be deployed. The increasingly prescribed nature of the school curriculum in the UK during the 1980s and 1990s and indeed the control of many aspects of pedagogy led to a model such as this being more or less inoperable. However, recent relaxations in curriculum and pedagogy, such as those encouraged by initiatives relating to creativity in education in England or by curriculum reform in Scotland, create very real opportunities for revisiting and reworking ideas of these sorts.

Indeed, it would be very misleading to suggest that there had been no developments in teacher research during the last part of the twentieth century. Through the persistent and committed efforts of a number of teachers and lecturers the legacy of Stenhouse has given rise to a range of networks of practitioner research in education (some of these are listed at the end of this chapter). In particular the concept of action research has bee...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Author

- Foreword

- PART 1 WHAT IS RESEARCH AND WHY DO IT?

- PART 2 WHAT DO WE WANT TO KNOW?

- PART 3 WHAT DO WE KNOW ALREADY AND WHERE DO WE FIND IT?

- PART 4 HOW WILL WE FIND OUT?

- PART 5 WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

- PART 6 HOW WILL WE TELL EVERYONE?

- References

- Index