Husbandry is a good word. When applied to any aspect of agriculture, by which I mean the management of land and life on the land, it comfortably embraces the facts and principles of science and economic production but it enriches these things with three special human qualities: duty, care and conservation. This opening sentence has, I confess, been stolen from my first ever book, whose relatively modest aim was to address the husbandry, health and welfare of young calves (Webster 1984). My present aim is rather more ambitious. It is to explore elements of the past, present and future husbandry of all farmed animals, viewed in a very broad perspective as the net sum of interactions between man, farm animals and the living environment wherever husbandry is practised, or abused.

The strategies that I shall present for the future husbandry of farm animals are based on the principle of respect: respect for science, economics and efficiency, respect for the welfare of the animals and respect for the living environment. I shall examine the proximate causes and contributors to current problems in animal husbandry, then advance arguments that may contribute to its recovery. Clearly it is not possible to consider the husbandry of farm animals in isolation. Due recognition will be given to the rising, but ultimately unsustainable, increase in demand for food from animals, and to socioeconomic issues such as food security and fair trade. However these issues have been well covered by other authors (FAO 2006; Wirsenius et al. 2010; D’Silva and Webster 2010). My focus is to seek constructive approaches to improving our impact on farm animals and their impact on the environment: simply expressed, how to do it properly. Part I, ‘Engaging with the problems’, will outline principles and arguments necessary to deal with current problems rather than simply grumble about them. It will consider how to reconcile our immediate needs to ensure economic and efficient production, farm animal welfare, food safety and human health, with our longer term responsibility to manage natural resources and the living environment (including coexistence between domestic animals and wildlife). Part II, ‘Embarking on solutions’, will present and discuss a series of constructive proposals that, in the words of my subtitle, suggest a future, or futures, for animal farming. These proposals will be considered on a global basis and will range from the most extensive pastoral systems to the mass production of food from animals in large, intensive peri-urban establishments, both assessed according to first principles of respect for science and respect for life.

Rules of engagement

The practice of agriculture: the working of the land and life on the land to provide us with the essentials of life, food and clothing (and ideally rather more than these) is, ever was and ever shall be bound by the fundamental laws of physics and chemistry – and these things don’t change. This point is so obvious that it should not really need to be said. It is however frequently ignored in the planning, accounting and audit of an agricultural industry driven by short-term objectives (day-to-day competition in costs and prices) and further distorted by market speculation in futures and derivatives.

All agriculture is driven by the inexhaustible (for our practical purposes) energy of the sun. However, the capacity of the land to sustain life, grow crops and feed humans and other animals is constrained by limits to the availability and quality of the land and water. For most of recorded time, farmers created wealth mostly from land that they didn’t own, at a rate that was determined by the food they could grow close to home and the feed their animals could harvest from further afield. All these things were, of course, critically dependent on a reliable source of soil and sunshine, warmth and water. The main reason why industrial agriculture in the developed world is so much more productive than subsistence farming, measured in terms of output, is because most of the inputs come from outside the farm. Materials are bought in as cheaply as possible and most of the energy comes not from the sun but from fossil fuels. I shall consider these issues in some depth. For the moment, the point I wish to make is that any audit of the long-term implications of agricultural practices, in this case the practice of animal husbandry, must take into account all the major factors that contribute to efficiency and sustainability in the use of renewable and non-renewable resources of energy, to balance in the use of finite but recyclable resources, such as carbon, nitrogen and other minerals, and to wisdom in the dispersal of agricultural wastes, which range from pig slurry to food past its sell-by date. These things are reviewed in Chapter 2, ‘Audits of animal husbandry’, which also explores ways in which farm animals can most efficiently and sustainably be incorporated into integrated systems for land use such as agroforestry, carbon sequestration and conservation grazing.

Chapter 3 addresses the issue of farm animal health and welfare. Welfare is viewed from two angles: ‘How is it for them?’ and ‘What is it to us?’ Their welfare can be defined by the extent to which they can meet their own physiological and behavioural needs, be ‘healthy and happy’. Our concern is, or should be, an expression of the same thing. We want them to be healthy and happy. Those in direct contact with farm animals have an obvious responsibility to care for them: to promote good welfare through good husbandry. It may be less self-evident but this responsibility extends to us all. It is not sufficient simply to care about animals, however sincere this feeling may be. In the case of the food animals our responsibility to care for them requires us to support farming systems that can demonstrate good husbandry leading to high standards of farm animal welfare. At all stages of the food chain, from farm to fork, animal welfare, together with other critical issues such as stewardship of the natural environment, needs to be built into the concept of food quality and rewarded appropriately.

Chapter 4 looks into the product: what we get from farm animals. Citizens of urban environments in the developed world equate this to food, meat, milk and eggs, arranged on supermarket shelves in a form that looks attractive, hygienic and as remote as possible from its source, the living sentient animal. For traditional and pastoralist farmers animals were and still are a source of transport and draught power, fuel and fertiliser, food and clothing. Wherever possible, food and clothing is harvested without killing the animal; eggs, milk or, in the case of the Masai, blood. Killing the animal for meat is a last resort (for both parties); not something to be considered lightly but reserved for special occasions such as the return of a prodigal son. In these societies it the custom to keep as many animals as possible, possibly as a status symbol but also as a reserve of wealth to be drawn on in times of climatic or financial stress. To a Western farmer accustomed to viewing animal production simply in terms of efficient conversion of the feed I buy to the food I sell, this may appear crazy, and indeed it can lead to real problems of overgrazing and desertification. However, on the basis of a more complete audit that takes into account, to give but one example, the fact that the cattle, horses, camels or yaks are not only providing food but also harvesting fuel and fertiliser at zero cost and contributing to the work of the farm, it begins to make a lot more sense. This is a nicely exotic illustration of the danger of arguing from limited premises.

While I shall consider several ways in which farm animals may contribute to our own welfare, most of this book will inevitably focus on food production. I begin with four facts of life.

- For urban citizens in the developed world, food has become cheaper and cheaper. Average expenditure on food (consumed in the home) in the UK was 26 per cent of household income in 1966; in 2010 it was 10 per cent (DEFRA 2011).

-

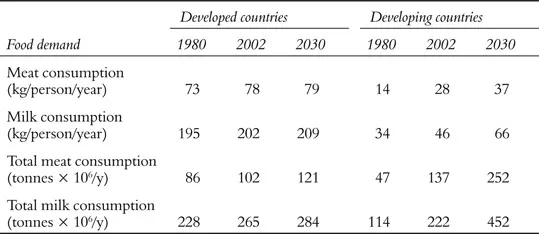

Notwithstanding the fact that vegetarians continue to thrive both individually and collectively, global consumption of meat consumption continues to rise because the great majority of people enjoy it and more and more can afford it. Table 1.1 presents past and projected trends in meat and milk consumption in developed and developing countries, expressed as total consumption per capita and consumption in toto (FAO 2006). In the developed world the increase in meat and milk consumption from 2002 to 2030 is predicted at 5 per cent. In the developing world (which

Table 1.1 Past and projected trends in meat and milk consumption in developed and developing countries (from FAO 2006)

includes India and China) the predicted increase is 96 per cent. Even so, consumption per capita in 2030 would still be less than 40 per cent that of omnivores in the developed affluent north and west.

- Nearly all of us in the developed affluent north and west who eat meat and other animal products eat much more than we need to meet our nutrient requirements (e.g. for essential amino acids, minerals and vitamins). In too many cases, our rate of consumption carries a serious health risk.

- The rate of increase in world consumption of meat and milk must decrease and soon. It has been estimated that ‘By 2030, if China’s people are consuming at the same rate as Americans they will eat 2/3rds of the entire global harvest and burn 100M barrels of oil a day, or 125% of current world output’ (Brown 1995).

The FAO publication Livestock’s Long Shadow (2006) presents a comprehensive quantitative analysis of current and projected systems of livestock production and their impact on the environment, and the news is nearly all bad. I quote from one particularly apocalyptic sentence: ‘the livestock sector is … the major driver of deforestation, as well as one of the leading drivers of land degradation, pollution, climate change … and facilitation of invasion by alien species’. This is, of course, all true (even the invasion by aliens bit).

Livestock’s Long Shadow and the recent book The Meat Crisis (D’Silva and Webster 2010) expound in detail on the environmental problems arising from the expansion in livestock farming (e.g. exhaustion of resources, land degradation, global warming) and the socioeconomic problems arising from disparities between supply, affordability and demand, viewed both within communities and at a global level. These are big topics and generate many questions. However, they will be discussed only briefly (perhaps too briefly) here, partly because they have been thoroughly covered elsewhere but mainly because these accounts of excesses are peripheral to the main themes of this relatively short book, which is primarily a science and ethics based investigation of what is being done at present and how it could and should be done better. One theme that will recur when considering big issues such as the feeding of grains (food for humans) to livestock, and the impact of livestock on the environment is that most investigations, and nearly all arguments, are based on limited premises, and most controversies arise from the fact that the various protagonists operate from different terms of reference. The farmer will say (correctly) that I have to make a living in a competitive world. The shopper will say (correctly) that when two batches of food (be it broiler chicken or baked beans) appear the same, it makes sense to buy the cheaper. The nutritionist will say (correctly) that consumption of meat and animal fats carries a risk to health. The animal welfarist will say (correctly) that farm animals have the right to a life worth living and the environmentalist will say (correctly) that animal farming as currently practised in both intensive and extensive systems presents serious threats to the quality and sustainability of the biosphere. Many of my arguments in the following chapters may be criticised on grounds that I have failed to take proper account of one or more cases of special pleading. Getting my retaliation in first, I would say that everything that is relevant to the big picture should be in the big picture but should not be allowed to blot out something else. If I were to attempt to consider in detail all the inputs to the analysis of these big questions, the book would become not only unreadable but impossible to write. Thus I shall not presume to offer definitive answers to these big questions, applicable in all circumstances and in all environments. My aim is to help you think about them in a way that is comprehensive, structured, scientifically sound, economically coherent and morally just.

Chapter 5, the final chapter in Part I, steps beyond the boundaries of biology and enters the worlds of philosophy, politics and economics. To quote Erwin Schrodinger: ‘The image of the world around that science provides is highly deficient. It supplies a lot of factual information and puts all our experience in magnificently coherent order but keeps terribly silent about everything close to our hearts, everything that really counts.’ As a quantum physicist and Nobel Prize winner, he has the right to draw attention to the limitations of science. Chapter 5 first explores philosophy, politics and economics of animal husbandry. Classic principles of ethics such as beneficence, deontology and justice are invoked to examine the rights and responsibilities of us humans, the moral agents to our moral patients, farm animals and the living environment. Having set out a moral basis for rights, responsibilities and value judgements, I then describe how these are incorporated into law and regulations, examine their difficult relationship with parallel, amoral, economic measures of value and explore how they may be reconciled through conventional politics and ‘politics by other means’, the power of the people.

includes India and China) the predicted increase is 96 per cent. Even so, consumption per capita in 2030 would still be less than 40 per cent that of omnivores in the developed affluent north and west.

includes India and China) the predicted increase is 96 per cent. Even so, consumption per capita in 2030 would still be less than 40 per cent that of omnivores in the developed affluent north and west.