![]()

I

What is the Self in the Context of Consumption?

![]()

I.I

Conceptions of the Self Within Consumption

![]()

1

Culture and the Self

Implications for Consumer Behavior

Shinobu Kitayama and Jiyoung Park

Introduction

Over the last two decades, substantial progress has been made on cultural differences and similarities in a variety of psychological processes (Kitayama and Uskul 2011; Markus and Kitayama 1991, 2010). We now know that many aspects of cognition (e.g. Nisbett et al. 2001), emotion (e.g. Mesquita and Leu 2007; Tsai 2007), and motivation (e.g. Heine and Hamamura 2007) show considerable variations across cultures. This is the case especially when comparisons are drawn globally between Western cultures (North American middle-class cultures in particular) and Eastern cultures (East Asian cultures in particular). Initially, much of this work focused on student populations at relatively elite universities in North America and East Asia.

More recent work, however, has validated conclusions from this work with non-student adult populations (e.g. Kitayama et al. 2010b; Kitayama et al. 2012; Park et al. 2012). Furthermore, researchers have begun to illuminate some significant within-culture variations by examining social structural or ecological factors including social class and educational attainment (Stephens et al. 2007), residential mobility (Oishi 2010), relational stability (Yuki et al. 2005), historical risk of parasite infection (Fincher et al. 2008), and voluntary settlement (Kitayama et al. 2006a). Further, the dimension of tightness (vs. looseness) of cultural rules and norms has been suggested as correlated with and, yet, distinct from individualism vs. collectivism or independence vs. interdependence – the dimensions that have been used typically to understand the existing cultural variations in psychological processes (Gelfand et al. 2011). This emerging literature is reviewed elsewhere (Kitayama and Uskul 2011).

The aim of the present chapter is to provide an updated review of empirical evidence on the cultural variations in cognitive, emotional, and motivational processes. In so doing, our intent is to situate the empirical evidence within a broader theoretical framework of culture and the self (e.g. Markus and Kitayama 1991), with a sharpened focus placed on implications for consumer psychology and consumer behavior.

Theoretical Framework: Self, Situational Affordances, and Psychological Processes

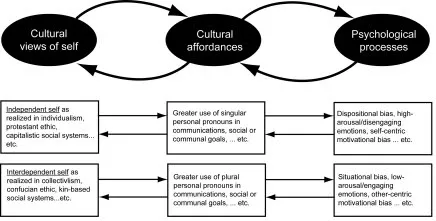

Our theoretical framework is illustrated in Figure 1.1. In Western cultures, particularly European-American middle-class culture, there is a strong emphasis on independence of the self from others. This view of the self as independent has many historical roots, including Greek emphasis on analytic thought and debate as a means for conflict resolution (Nisbett 2003), Protestantism (Sanchez-Burks 2005; Weber 1904/1930), and Enlightenment conceptions of freedom, self-interest, and social contract (e.g. Smith 1759). These ideas have historically been used to generate various practices, conventions, and more domain-specific lay theories, resulting in individualistic ethos and cultural systems. As a consequence, various elements of cultural contexts of Western societies today appear to have the potential to induce behaviors that are matched to or congruous with the very notion of independence.

Figure 1.1 Theoretical framework linking cultural views of self, cultural affordances, and cross-culturally variable psychological processes

In North American middle-class culture, for example, there is a strong emphasis on personal self in communicative practices. In particular, singular, first-person pronouns such as “I,” “my,” “me” and “mine” are frequently used (Kashima and Kashima 1998). Likewise, linguistic practices of North America emphasize personal goal pursuit (e.g. “What do you want?” “Which wine would you like?” “Be all you can be!”). The potential of cultural practices to induce certain psychological responses have been called cultural or situational affordances (Kitayama et al. 1997). Western cultural contexts in general and North American middle-class contexts in particular are expected to carry a number of affordances for independence.

Individuals who are born in the environment characterized by these affordances are likely to develop corresponding independent psychological tendencies, including cognition, emotion, and motivation. They may, for example, become more focused in attention vis-à-vis their personal, current goals and desires. Or they may acquire conceptions of good life, well-being, and happiness that are primarily personal rather than social or interpersonal. Moreover, their motivations may be anchored in their own personal goals. These psychological tendencies are acquired through repeatedly performing cultural practices based on the model of the self as independent. Such tendencies are therefore likely to become more or less automatic and, thus, often occur unconsciously or subconsciously without any awareness, although they are likely to be highly sensitive to various contextual cues at the same time. Kitayama et al. (2009) called these psychological tendencies implicit independence.

In contrast, Asian cultures tend to have a contrasting view of the self as interdependent. Because the self is embedded in significant relationships or social groups, it is made meaningful in reference to such relations and groups. This view of the self as interdependent also has some notable historical roots, such as Buddhist cosmology that unites man and its surrounding and Confucianism with its emphasis on social hierarchy. These ideas are at the heart of traditional, feudalistic social order wherein kin or quasi-kin relations are regarded as central. Altogether, there emerge collectivistic cultural ethos and social systems. As a consequence, various elements of cultural contexts of Asian societies today have the potential of inducing behaviors that are congruous with the notion of interdependence. For example, plural first-person pronounces such as “we,” “our,” “us” and “ours” are likely to be used much more frequently than their singular counterparts (Kashima and Kashima 1998). Or, group goals or relational goals are emphasized in daily discourses. Asian cultural contexts, in other words, are expected to carry a number of situational affordances for interdependence.

By repeatedly engaging in and performing various cultural practices that afford interdependence though socialization, Asians are likely to acquire correspondingly interdependent cognitive, emotional, and motivational tendencies that are largely automatic and subconscious or, in other words, implicit. They may, for example, become more holistic in attention vis-à-vis many socially relevant stimuli in the environment including other people. Or they may acquire conceptions of good life, well-being, and happiness that are much more social or interpersonal – the one that is anchored in social harmony. Moreover, their motivations may also be closely tied to social expectations. Social expectations are likely to be internalized to such an extent that one’s own goals and desires are finely coordinated or in large part concordant with the expectations held by significant others.

Our theoretical framework emphasizes that cultural differences in psychological processes are mutually interdependent with cultural affordances that are realized in the practices, conventions, as well as other scripted behavioral patterns of the culture at issue. These behavioral patterns or practices are in turn linked historically to the ideologies and philosophical thoughts that are available in the respective societies and cultures. According to this conceptualization, psychological processes that are formed through repeated engagement in a given set of cultural practices may be expected to be most likely to be recruited again when these practices are in fact available in a given situation. We may therefore expect that European Americans may be most likely to be independent in their thinking, feeling, and acting (i.e. cognition, emotion, and motivation, respectively) when the relevant cultural affordances are activated and reinstated in any given situation and, conversely, Asians may be most likely to be interdependent in their psychological tendencies when the corresponding cultural affordances are reinstated. As we shall see, recent work on situation sampling as well as cultural priming has provided substantial evidence for this possibility.

Evidence for our theoretical framework comes from many different sources. Given space limitation, however, we will focus on three relatively specific domains – i.e. analytic vs. holistic cognition, engaging vs. disengaging emotion, and self-centric motivation. In each case, we will summarize overall East–West cultural differences that have been identified. In so doing, we will emphasize both behavioral and neural evidence, illustrating the profound degree to which culturally shaped implicit psychological tendencies are inscribed into brain processes. We will then discuss the nature of situational affordances that have been empirically linked to these differences. Finally, there will be a discussion on what the current evidence on cultural variation in specific psychological processes might imply with respect to consumer psychology and consumer behavior.

Analytic and Holistic Cognition

Attention

The culturally shared views of the self have been suggested to have profound influences on basic attention processes. In Western cultures, individuals are encouraged to discover their internal attributes such as desires and personal goals, and therefore they may be expected to focus their attention on events that are relevant to such desires and goals. As a result, their attention may become focused. This cognitive style, which is anchored in a focal object in lieu of its context, has been called analytic (Nisbett et al. 2001). In contrast, in Eastern cultures individuals are more attuned to various aspects of ever-important social relations and, as a consequence, they may be expected to attend more broadly to a focal object as well as to its surrounding context, drawing inferences about the relationship between the object and its context. This mode of cognition has been called holistic (Nisbett et al. 2001). These predictions have been borne out. For example, when presented with an animated vignette of an underwater scene and subsequently asked to remember what they saw, European Americans were more likely to recall focal objects, whereas Japanese were more likely to refer to contextual information as well as relationships between the focal objects (Masuda and Nisbett 2001).

Similar cultural variations are also evident even when the stimuli are completely non-social. In one study, participants were shown a line drawn within a square frame. Immediately afterward, they were presented with another square of different size and asked to draw a line in this new square frame (Kitayama et al. 2003). In one condition, participants were asked to draw a line that was identical in absolute length to the first line (i.e. absolute task). To perform this task well, they have to ignore the square frames. In another condition, however, participants were asked to draw a line that is proportional to the height of the respective square frames (i.e. relative task). To perform this task well, they have to incorporate the size of the respective squares into account. Consistent with the hypothesis that attention is narrowly focused on an immediate object for European Americans, performance of European Americans was significantly better in the absolute task than in the relative task. Also in support of the hypothesis that attention is holistically allocated to both a target and its context for Asians, performance of Asians was significantly better in the relative task than in the absolute task.

Dispositional Bias

In social perception, it is a social actor that often constitutes the focal figure of a scene. Given the attention difference across cultures summarized above, European Americans may be expected to focus their attention on the target person, thereby making inferences on the person’s internal and dispositional attributes. In contrast, Asians may be more holistic, allocating more attention to the situation in which the target person is embedded. In line with this reasoning, people from Western cultures have been found to show a strong dispositional bias or the fundamental attribution error (FAE) (Ross 1977) – the tendency to explain another person’s behavior based on the person’s disposition even in the presence of obvious situational constraints. As may be predicted, however, it has been found that Asians are much less susceptible to this bias, due to their holistic cognitive tendencies. For example, European Americans have been shown to make dispositional inferences about a target person even when the situational constraint on the behavior of the target person is made salient (Gilbert et al. 1988). In sharp contrast, under comparable conditions, Asians – both Koreans (Choi and Nisbett 1998) and Japanese (Masuda and Kitayama 2004) – show little or no dispositional inference.

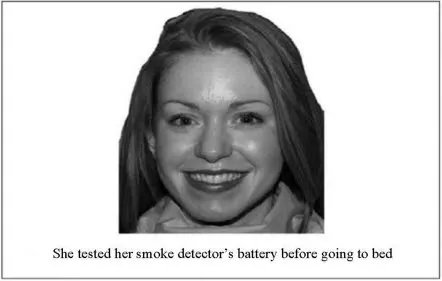

More recent work finds that this cultural difference is likely to occur very early on in the sequence of information processing at the stage where dispositions are automatically inferred from behaviors. Na and Kitayama (2011) had European and Asian American participants memorize a large number of pairings of a face and a behavior that implies a certain trait (e.g. “Judy checks a fire alarm before going to bed,” which implies “cautiousness”). A sample stimulus is shown in Figure 1.2. If the dispositional inference is truly automatic, next time when they are shown the face of the same person, it may be this personality trait (“cautious”) that automatically occurs to their mind.

Figure 1.2 A sample stimulus used in the Na and Kitayama (2011) study

To determine the extent to w...