- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Health and Disease

About this book

A report from research in the MIT Sea Grant College Program. Discusses the relationship between particular fatty acids found only in fish oil, and human health. Presents and evaluates information on the health effects of dietary fats generally; evidence that fish oil consumption affects the incidenc

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Health and Disease by Lees,Robert S. Lees in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technologie et ingénierie & Sciences de l'alimentation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I:Health Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

1

Impact of Dietary Fat on Human Health

Robert S. Lees

Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology and New England Deaconess Hospital

Boston, Massachusetts

INTRODUCTION

Human beings, for many centuries, have attributed almost mystical properties to their dietary fats. The ancient Romans not only ate their beloved olive oil, they anointed themselves with it. Modern Americans not only eat fish in hope that its oil will keep them healthy, they swallow fish oil capsules as a drug. In this discussion, I will attempt to review the salient facts concerning dietary fat and its effects on human health. My goal is to provide an overview, since the details of each of the major categories of disease with which dietary fats have been associated will be given by others later in this volume.

To my mind, the modern era of dietary fat research began with an animal, rather than a human experiment. Parenthetically, I will cite relatively few animal data here, because laboratory animal experiments are often not extrapolable to the situation in the free-living human being. The experiment I have in mind, however, is highly extrapolable. In the early 1920s, Simon Henry Gage and Pierre Fish, at Cornell University, fed a sheep some vegetable oil colored with a fat-soluble dye called cochineal. Then they dissected the sheep and found that the animal’s intestinal lymph, or chyle, contained tiny droplets of fat which contained the dye, and that these droplets passed into the blood via the thoracic lymph duct. Finally, after several hours, the sheep’s fat turned pink. In a preliminary publication (Gage, 1920) in Cornell Veterinarian, Gage named these small particles “chylomicrons,” the name we use today. In a later full publication (Gage and Fish, 1924), the investigators postulated that the function of chylomicrons was to transport dietary fat into the lymph and from there to the blood-stream and sites of storage or utilization, the function that they are still thought to fulfill. This classic experiment in fat metabolism is, to my knowledge, the first metabolic experiment to use a tracer. The studies of Gage and Fish, which graphically showed the passage of dietary fat through the lymph and blood to the depot fat, set the stage for the next half-century of studies on the metabolism of dietary fat and its effects on human health.

In the spirit of Gage and Fish, we must turn to the composition and the metabolism of dietary fat in order to understand its effects on health. What we eat (Table 1) contains three major lipid classes, triglycerides, phospholipids, and sterols, plus a number of minor components of varying, sometimes major, importance. This list, which is by no means comprehensive, gives us some idea of both the variety and the variability of human dietary fat intake. Commercial vegetable oils, for instance, may contain almost pure triglycerides, the sterols and phospholipids having been removed to ensure clarity. Egg yolk, by contrast, is about 65% triglycerides, 25% phopholipids, and 5% cholesterol. When discussing human disease, one must distinguish among substrate effects, the effects of natural minor components of metabolic importance, and the effects of toxic minor components. Let us turn at this point to normal human fat metabolism.

Component | Subclasses | Natural/otherwise | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|---|

Triglycerides | Saturated | Natural/synthetic | |

Monounsaturated | Natural/synthetic | 65-95+ | |

Polyunsaturated | Natural | ||

Phospholipids | Lecithins | Natural/synthetic | 1-30 |

Other phosphatides | Natural | ||

Sterols | Cholesterol | Natural | |

Other animal sterols | Natural | 0-5 | |

Plant sterols | Natural | ||

Vitamins and | Retinol | Natural/synthetic | |

provitamins | Caroteins | Natural | <1% |

Vitamin D | Synthetic | ||

Tocopherols | Natural/synthetic | ||

Hydrocarbons | Squalene | Natural | <1% |

Alkanes, alkenes | Environmental contaminants | ||

Polycyclics | |||

Antioxidants | BHA/BHT | Added to prolong shelf life | |

Propyl gallate | <1% | ||

Tocopherols | |||

Environmental toxins | DDT | Insecticide | |

PCBs | Insulating fluid | <<1% | |

Mycotoxins | Food spoilage | ||

Other toxins | |||

Other additives | Silicones | Nonstick agents | <<1% |

HUMAN FAT METABOLISM

Fat fulfills multiple functions in the human body, acting as the major metabolic fuel to meet caloric needs, as the major structural component of the cell wall, and as an essential precursor of several hormones critical to normal existence. A complete review of human fat metabolism is beyond the scope of this chapter and this volume; the interested reader is encouraged to seek out other, excellent, sources of this information (Lewis, 1976; Havel et al., 1980, Assmann, 1982). However, the major pathways of fat metabolism will be discussed here, as they are essential to understanding the topics that follow.

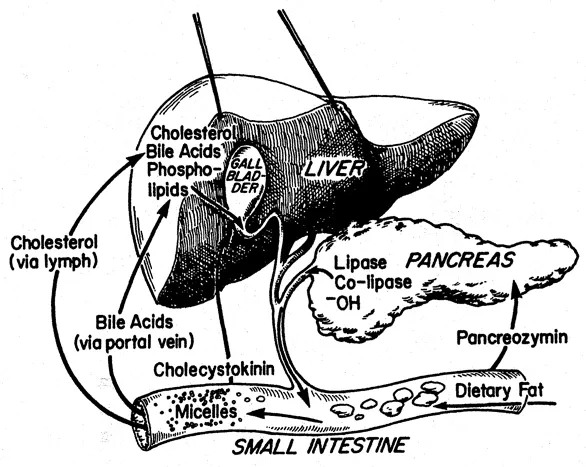

Of the three major lipid classes in dietary fat, sterols have the simplest metabolic pathway in most respects, and triglycerides the most complex. Nevertheless, we will begin with the latter, as it is necessary to understand triglyceride metabolism in order to place that of the other lipids into proper perspective. The majority of dietary fat is triglycerides, which pass through the stomach unaltered by its acid pH and the gastric proteases. In the small intestine (Fig. 1), the pH is alkaline, and the pancreatic juice that is secreted into the small intestine contains a powerful lipase (Semeriva and Desnuelle, 1979), which with its polypeptide colipase (Borgstrom, 1979) has the ability to hydrolyze triglycerides to monoglycerides and 2 moles per mole of free fatty acids (FF A). Pancreatic lipase is virtually inactive on triglycerides in their usual bulk state, however. The enzyme’s activity depends on the emulsification of dietary fat into micelles, small spheres of triglycerides, along with any other nonpolar lipids present in the dietary fat, such as sterol esters and fat-soluble vitamins, with a surface coat of phospholipids, free cholesterol, and bile acids. Most of the first two and all of the third of these polar lipids of the micellar surface come from the bile, which is secreted by the liver, with intermediate storage in the gallbladder and bile ducts. Bile is secreted into the small intestine when fat enters it from the stomach. This process (Fig. 1) is triggered by the hormone cholecystokinin, which is secreted by the duodenal mucosa when fat comes into contact with it.

Figure 1 The mechanisms of fat digestion and absorption (see also Fig. 2). Dietary fat is solubilized by bile acids, phospholipids, and free cholesterol, all of which enter the gut from the gallbladder bile. It is then digested by pancreatic lipase which is secreted in the pancreatic juice. Bile acids are absorbed directly and retransported to the liver via the portal vein. Cholesterol and triglycerides are absorbed as chylomicrons; the cholesterol is returned to the liver via a circuitous route. See text for further details.

The monoglycerides and free fatty acids produced by lipase activity are absorbed by diffusion into the gut mucosal cells and there resynthesized into triglycerides, with the admixture of 10-20% of endogenous fatty acids (i.e., fatty acids from the body stores, not from the digested fat) and assembled into chylomicrons. The chylomicrons, as described by Gage and Fish, pass into the intestinal lymphatics, from there into the large lymphatic chamber in the abdomen called the cisternal chyli, and finally via the thoracic (lymphatic) duct into the venous blood (Fig. 2). The chylomicrons then pass through the heart in the venous blood, and chylomicrons are distributed to the entire body via the arterial and finally the capillary circulation. There, something akin to the mirror image of chylomicron production occurs. As the chylomicrons move along the capillary surf ace, their triglycerides are lipolyzed by the concerted action of two important enzymes-lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and lecithin:cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT). LPL and a related enzyme, hepatic lipase, hydrolyze the triglycerides to glycerol and free fatty acids. The free fatty acids diffuse through the capillaries into the underlying parenchymal cells, where they are either burned as metabolic fuel or resynthesized to triglycerides and stored. The glycerol is returned via the blood to the liver, where it enters the hepatic glycerol pool and may be resynthesized into triglycerides, converted to carbohydrate, or it may undergo one of many other metabolic reactions. Since as much as 100 g of dietary fat may be absorbed and transported through the blood each day, the process of chylomicron formation and transport must be swift and efficient. The half life of chylomicrons in plasma, for example, is about 10 min in normal human beings. Thus, the triglyceride fatty acids from dietary fat are rapidly and efficiently transported to peripheral tissues, where they may be stored, as in the adipose tissue, or burned for energy as occurs in muscle. Many metabolic studies (Fredrickson and Gordon, 1958; Fritz, 1961; Ca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Part I: Health Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- Part II: Sources of Dietary and Pharmacological Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- Index