- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Food irradiation has been in the news lately, and this news strongly favors the consideration of food irradiation as a practical, economical method for improving food safety and shelf life.

This new edition of a popular guidebook provides an updated, detailed, readable survey of the past, present and future of food irradiation. It covers a wide variety of topics ranging from the scientific basics to an examination of the many objections to food irradiation. Also included is a detailed discussion of the role of food irradiation in preventing a variety of foodborne diseases.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Food Irradiation by Morton Satin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Food Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Food Irradiation

A prerequisite to appreciating all the issues involved in the food irradiation debate is an understanding of the technology and its history. But prior to launching into this subject it is important to examine the name of the technology since this itself has played an important role in the controversy.

There is no doubt that the name food irradiation makes most people immediately think of nuclear radiation. Many of us have seen the terrible pictures of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after they were hit with the first atomic bombs. Since that first episode, the threat of nuclear war has been our constant fear. Despite the end of the cold war and the warming of relationships between all the great military powers, the fear of a nuclear confrontation still plagues us. In fact, the dismantling of the former Soviet Union has resulted in a weakened central infrastructure to control the vast number of nuclear weapons still in existence. Recent reports of the attempted smuggling of weapons-grade uranium out of Russia and Eastern Europe are an inevitable result of this situation. As a consequence, the chance of some radical power getting hold of this technology and using it as a means of blackmail or mass destruction is still within the realm of possibility.

Aside from its obvious connection to the atomic bomb, nuclear radiation is also a fear associated with the nuclear power industry. Notwithstanding the benefits that have already accrued from the use of nuclear energy, the specters of Three Mile Island and Chernobyl continue to haunt us–and rightly so.

Many countries have chosen to be nuclear free in an attempt to avoid any possible accidents from such power plants in the future. In making such decisions, the risks of the technology are normally weighed off against the benefits. It must be understood, however, that risks and benefits are not absolute values. Depending upon time, the technology in question, and the general circumstances of the world, the risks and benefits can change. Risks can be reduced through improved or more reliable technology. Benefits can increase when other alternatives become less attractive; for example the environmental buildup of acid rain due to high-sulphur coal burning. Unfortunately, self-interest and power politics often exert a far greater influence than they should in the final assessment of risks versus possible benefits.

Nuclear-powered electricity plants were designed to replace coal-powered plants because they were cheaper and caused less apparent pollution. Nevertheless, many countries feel their conventional sources of energy are more suitable, and currently prefer the risks associated with them, rather than with nuclear energy. Only time will tell if these judgments will change. There is no question in anyone’s mind, however, that accidentally released radioactivity or uncontrolled nuclear radiation is a very frightening affair. Fortunately, it has nothing to do with irradiated foods. Unfortunately, it has very much to do with the erroneous perception of what food irradiation actually is.

In fact, the mistaken association of food irradiation with nuclear radiation is so great that food irradiation proponents resent the name and blame it for all the public’s irrational fears of the process. They would love to change the name, not to conceal the technology, but to remove its frequent association and confusion with nuclear radiation.

On the other hand, opponents adore the term food irradiation. Since all the scientifically accepted evidence supports the safety of irradiated foods, association of the process with all the fears of nuclear radiation has become their most effective tool of negative influence. The classic question asked is “Do you want to have your food nuked?” The very name of the process is enough to frighten anyone who knows little about it. Jokes about glowing or radioactive foods are not funny for those who actually believe them. Thus, the term food irradiation itself, has been part of the problem.

If, however, there is sufficient knowledge of the subject to prevent confusion and misunderstanding, there should be no reason to change or avoid the name. Thus, in the optimistic hope of being able to convey a deep enough understanding of the process to eliminate any confusion with nuclear radiation, the term food irradiation will be used freely throughout this book.

(Because gamma rays ionize certain molecules during food irradiation, the process is quite correctly called ionization in France. The term irradiation is so intimately associated with nuclear radioactivity in the French language that its use, in relation to food processing, is grossly misleading. As a result, ionization has become the generally understood term equivalent to food irradiation in the French language. The same argument can be applied to other languages.)

What Is Irradiation?

Before reviewing the history and applications of food irradiation, it is first necessary to understand what the process actually is. Unfortunately, a certain amount of technical jargon is unavoidable in explaining the subject.

In order to understand the term irradiation, it is first necessary to understand the word radiation.

The Van Nostrand’s Scientific Encyclopedia defines radiation as follows [3]:

Radiation

1. The emission and propagation of energy through space or through a material medium in the form of waves: for instance the emission of electromagnetic waves, or sound and elastic waves.

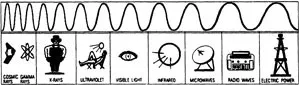

2. … The term radiation or radiant energy, when unqualified, usually refers to electromagnetic radiation; such radiation is commonly classified according to frequency, as radio frequency, microwave, infrared, visible (light), ultra-violet, x-rays, and γ (gamma)-rays.

In fact, the most common use of the term radiation, in both a scientist’s as well as a layman’s sense, refers to waves or rays in the electromagnetic spectrum. The electromagnetic spectrum is the full range of frequencies or wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation. This is most commonly pictured as a ruler along which the range of frequencies is spread. Many of the regions of the spectrum are familiar to most of us. Microwaves, infrared, ultraviolet and X-rays are all fairly common sources of energy we regularly encounter. The electromagnetic spectrum is diagrammed in Figure 1.1.

Therefore, irradiation refers either to exposure to, or illumination by, rays or waves of all types. The Webster Dictionary describes irradiate as follows [4]:

To illuminate or shed light upon; to cast splendor or brilliancy upon, to illuminate; to penetrate by radiation; to treat for healing by radiation, as that by X-rays or ultraviolet rays.

When you lie in the sun to get a tan, you are being irradiated. Depending upon the sensitivity of your skin, and the intensity of exposure, this form of irradiation can simply make you look good or it can make you very ill. Common sense and the use of protective suntan lotions have lessened the risks of skin disease associated with excess exposure to the sun’s radiation, and this pastime is still enjoyed by millions of people. If the suntan lotions had to be (accurately) called radiation protection cream or irradiation lotion, it would definitely put people off. However, most would eventually return to the use of these lotions once they knew what they were, and understood the benefits of their use.

In fact, as will be discussed later, the term irradiation has been used in precisely this way in the past. Vitamin D is naturally formed by the action of sunlight upon our skin. In order to improve its vitamin D content, milk was exposed to ultraviolet light and was sold as irradiated milk [5]. This ultraviolet irradiation process is still in use in some parts of the world.

Visible light is generally considered to be the range of wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum which are least hazardous to humans. This is simply because light doesn’t penetrate deeply past our protective skin, and consequently does not affect our sensitive internal organs. Microwaves, X-rays, gamma-rays, and cosmic rays, on the other hand, have greater penetrating power and can be dangerous. If one receives enough exposure directly from these rays, one will certainly be injured and possibly even die. That is why people would no more walk into a microwave oven than an irradiation chamber. That is also why strict standards of personnel control and exposure are applied to all forms of penetrating radiation.

Radiation of various wavelengths is employed to carry out tasks which could not normally be done otherwise. For instance, the convenience of microwave ovens allows us to heat up foods and beverages more rapidly than ever before. The radiation fears people originally had of these ovens have been overcome simply by time, familiarity and their routine presence on the market. People may differ in their opinions as to how well microwaves perform in the cooking of various foods. Some people love cakes made in the microwave, and others wouldn’t touch them. However, no one can deny that these ovens can heat up foods with extraordinary speed. This can be very convenient after a long day at work, or when heating up various prepared dishes for company. Yet, there was a time when there was a genuine doubt if the public would overcome its fear of microwave ovens and the foods prepared in them. There are still people who distrust microwave ovens and don’t use them. That is their right and their choice.

Ultraviolet radiation, on the other side of the electromagnetic spectrum, is used for many things. In the pharmaceutical industry, it is used to keep rooms sterile, and is employed in certain critical areas of the food industry to minimize microbial problems. Ultraviolet radiation is used to cure certain epoxy glues and resins. Degradable plastic packaging, designed to reduce environmental clutter, depends upon the ultraviolet rays that are present in sunlight to achieve its desired result.

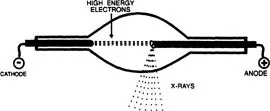

Almost everyone is familiar with the radiation from X-rays, shown in Figure 1.2. Soon after their accidental discovery by the German physicist, Wilhelm Roentgen, in 1895, the penetrating power of X-rays was put to use by physicians to examine our bodies without surgical invasion. Damaged organs, broken bones and cancerous tissues can all be detected prior to treatment. The newer CAT (computer aided tomography) scanners have brought this beneficial technology to unparalleled levels of sophistication.

X-rays are also used to individually examine the thousands of parts that make up the jet engines that power today’s airplanes. The unique ability of X-rays to detect stress cracks and other abnormalities has provided us with unparalleled reliability in these new engines. There still are occasional engine failures, but this modern technology, intelligently applied, has resulted in an overall level of performance that is truly astonishing. This level of reliability has also served to positively affect consumers’ perception of the benefits versus the risks of air travel.

Radioactivity

In spite of the fact that the definition of the term radiation includes the entire electromagnetic spectrum, most people identify the word with radioactivity. There is also a popular belief that both radiation and radioactivity are relatively new phenomena. They are not.

Radiation and radioactivity are the result of the formation of our universe billions of years ago. Although they have been a normal part of our planet’s existence since its birth, it has only been one century since we have become consciously aware of them.

It all started from the accidental discovery, in 1895, by French scientist Henri Becquerel, that natural uranium could affect photographic plates which were protected by lightproof paper. Within three years, Marie and Pierre Curie revealed the natural breakdown of uranium into the elements polonium (named after Poland, Marie’s birthplace) and radium. This breakdown was accompanied by measurable radiations, which Marie called radioactivity.

From the very start of radiation research, the dangers of exposure to radioactivity were known. In fact, both Henri Becquerel and Marie Curie suffered from effects of direct exposure. Despite these hazards, research continued both into the peaceful and the military uses of this new discovery.

In reality, most of the work was directed at trying to reveal the physical structure of atoms. In order to grasp how radioactivity is formed, it is essential to visualize what atoms are like. The easiest way to picture atoms is to imagine a solar system. Just as the sun is the center of our solar system, so is the nucleus the center of the atom. The nucleus is extremely dense and is made up of closely packed heavy particles–protons and neutrons. Proton particles carry a positive electrical charge and neutrons, as their name suggests, are neutral–they don’t carry any charge. In order to balance off this central positive charge in the nucleus, atoms have electrons which spin around the nucleus, in much the same way as our planets orbit around the sun. This results in atoms with a neutral electrical charge, as diagrammed in Figure 1.3.

It is the protons and electrons that determine which element the atom actually is. For instance, hydrogen is the lightest atom because it has only one proton in the nucleus ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Introduction

- 1. Food Irradiation

- 2. Pasteurization

- 3. Foodborne Diseases

- 4. The Use of Irradiation to Prevent the Spread of Foodborne Diseases

- 5. The Prevention of Food Losses after Harvesting

- 6. Advocacy Objections to Food Irradiation

- 7. Irradiated Foods and the Consumer

- 8. Irradiation and the Food Industry

- 9. Some Final Thoughts

- References

- Index

- About the Author