![]() Part I

Part I

Habsburg Visual Culture: Tapestries, paintings and festivals at court![]()

1

The language of triumph: Images of war and victory in two early modern tapestry series

Fernando Checa Cremades*

By the end of the Middle Ages a particular way of representing the image of warfare had developed in Europe, in which a narrative language was often employed in a monotonous way, imitating the literary genre of the chronicles of history.1 When transferred to images this language proved a complex way to highlight a military campaign’s most relevant exploits, to call attention to specific individuals, or to underscore the role played by the heroes. This language of triumph achieved its greatest splendour in the frescoes with a martial theme that decorated European castles, palaces and residences. This language was particularly deployed in the tapestry series that were among the customary ways of decorating the large rooms in noble, religious and royal buildings.

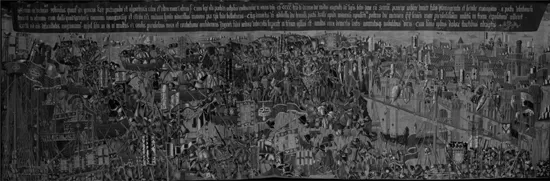

The four tapestries that comprise the series The Conquest of Asilah and Tangiers by Afonso V of Portugal (c. 1475), known as the ‘Pastrana tapestries’, are an excellent example of this artistic development. Together they form a series of around 45 metres (49 yards) in length that develops a panoramic overview of this military campaign fought in North Africa. Most certainly commissioned by their leading protagonist, King Alphonse V of Portugal (r. 1438–1477), this series is one of the most powerful images of warfare in Renaissance European art that is linked to an actual historical event, such as Alphonse V of Aviz’s 1471 expedition.2

The famous series of tapestries The Conquest of Tunis (1546–1553), commissioned by Mary of Hungary (1505–1558) in honour of her brother the Emperor Charles V (r. 1519–1558),3 undoubtedly represents the culmination of the representation of warfare and the image of triumph as developed over the course of the Renaissance. These tapestries were among those most often used by the Spanish Habsburgs in festivals and celebrations of every kind, a fact which signals the symbolic and representative importance attributed to them. The series expresses the complex and contradictory characteristics that conveyed the public image of the Emperor Charles V at the end of his reign.4

The aim of this chapter is to analyse the complexity and disparity of what could be termed ‘the language of triumph’ in a medium such as tapestry during one of its moments of greatest splendour, which developed from the end of the fifteenth century to the mid-sixteenth century. To this end, this chapter explores two series of fundamental importance: The Conquest of Asilah and Tangiers by Alphonse V of Portugal (Pastrana, Colegiata de Santa María), dated to c. 1475; and The Conquest of Tunis (Madrid, Patrimonio Nacional) completed in 1553. This chapter explores how these two artistic endeavours express in different ways the languages of triumph and military victory using the narrative of a historical chronicle. Thus this analysis enables us to contextualize the functions of the tapestries and the use of such representations of warfare in Renaissance festivals and commemorations.

The Conquest of Asilah and Tangiers by Alphonse V of Portugal: A Series Woven in the Workshop of Pasquier Grenier in Tournai

The tapestries of this series were almost certainly woven in the workshop of Pasquier Grenier (1447–1493), which was active in Tournai during the second half of the fifteenth century, as they reveal analogies in terms of composition and conception with other series on military themes produced by this workshop, such as Deeds of Alexander, c. 1455–1466 (Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphili).5 This would explain the images’ intricate narrative, as well as the taste for the compositional horror vacui, which was a typical feature of the Tournai workshops’ style at this time. The majority of the Latin inscriptions that accompany the series have been damaged or lost. Despite the extent of the information provided, it is insufficient for a complete, comprehensive reading of the series; instead the spectator is left fascinated by its panoramic spectacle.

The narrative formed by the four pieces has to be read in sequence from left to right, as the military encounters unfold visually one by one. The story represented has strong parallels with the chronicles written at the time, especially that of Ruy de Pina (1440–1521).6 The tapestries recount:

1. Landing in Asilah (Figure 1.1). In this first tapestry the action is introduced through the depiction of the Portuguese boats appearing on the left-hand side, filled with soldiers and profusely ornamented with heraldic devices. The central part of the tapestry shows King Alphonse V and his son John overseeing the landing of the troops from aboard their boat, and the march towards Asilah. The latter includes a second image of the royal figures, this time shown on foot. The arrival at the city is shown on the right-hand side. The tapestry develops a movement from left to right and this is the basic direction in which it has to be read.

2. Siege of Asilah. Both this tapestry and the one that follows lack any internal movement and so should be viewed by working from the centre, rather than from left to right. The scene is organized with the image of the city besieged by the Portuguese at its centre. The king and his son on horseback are depicted symmetrically on the right and the left in strict profile; the Grenier workshops produced a number of figures in the same manner in other tapestry series, such as Deeds of Alexander of which only the petits patrons have survived.

3. Assault on Asilah. This is also a static scene. Again the city is in the centre and the royal protagonists on horseback are shown on the left- and right-hand sides. The difficulty in reading the tapestries comes from the abundance and prolixity of the scenes depicting the assault on the fortress and the horror vacui that pervades the whole series.

4. Capture of Tangiers. The history of the campaign concludes in this final tapestry, which moves, like the first, from left to right. The capture of Asilah has now taken place and the army, without the royal protagonists, begins its march towards Tangiers. As in the first scene, this can be divided into three parts: the march towards Tangiers is an authentic triumphal parade, which occupies the left-hand side of the composition; the image of the city is in the centre; and on the right-hand side, also moving in the same direction, the flight of the Muslims leaving the city is shown. This is arguably one the best images of the Muslim world seen through European eyes produced during the later fifteenth century.

In conclusion, the four tapestries compose a panorama of war governed by a deep compositional coherence: from the initial appearance of the ships in the first tapestry to the final scene of the fleeing Muslims. The series is thus an extraordinary (woven) fresco, which provides abundant and detailed information on the military world of the period. Weapons proliferate (artillery, firearms, lances, shields) and armour of every type is depicted, thereby documenting the state of these elements in the mid-fifteenth century. The luxurious armour and garments of the two royal protagonists, and the saddlecloths and bridles of their mounts, help to distinguish them from the multitude of other figures. A similar point may be made with regard to the symbolic use of heraldry, which was one of the most important iconographical and cultural elements at that time. Without a thorough knowledge of heraldry we can understand neither the architectonic ornamentation of palaces and public religious buildings at the end of the fifteenth century nor the iconography of festivals and triumphal entries in early modern Europe, of which we lack an abundant corpus of images.7 This series of tapestries, like others from the end of the fifteenth century and even from the beginning of the sixteenth century are essential aids to imagining the special world of the Joyeuse Entrée, of which we possess many textual accounts but very few images. In essence, the visual style of the tapestry in its narration of the historical events imitates the chronicles of history that were replicated in the festival booklets of the period.8

1.1 Landing in Asilah, Pastrana Tapestry Series Copyright © 2014 Fundación Carlos de Amberes

The series allows us to consider the significance of the image of kingship and the representation of political and military power at the time. In addition, the tapestries show that martial iconography was in a period both of splendour and transition towards ‘modernity’. The abundance of heraldic elements and the actual images of Alfonso V and his son continued to draw on the language of medieval knighthood. However, the presence of the boats, the fortification systems and the easily identifiable firearms inform us of a new concept of warfare, a ‘modern’ warfare, which was taking hold towards the end of the fifteenth century.

The Conquest of Tunis, A Work By Willem de Pannemaker

The Conquest of Asilah series was owned by the Infantado family from at least 1532 onwards, although the exact date at which they acquired it and under what circumstances has not been ascertained.9 The Infantado family were great collectors of tapestries and had an important armoury, among many other works of art. The Conquest of Asilah series was used on repeated occasions to decorate their palace in Guadalajara.10 However, despite this repeated use, the image of warfare underwent an important evolution across Europe from the end of the fifteenth century. It should be noted in passing that the languages and motifs developed from medieval origins continued to be used in ‘decorative’ programmes, but this is an issue that cannot be addressed within the constraints of this chapter. Suffice it to say that in the field of tapestries, the image of war underwent an important advance in series such as The Battle of Pavia (c. 1528–1531), the cartoons for which were created by Bernard Van Orley (c. 1491–1541), and it reached its peak, as stated above, with the commission of The Conquest of Tunis series.11

Any study of these tapestries must begin by addressing the problem of the disparity between the date on which the events recounted took place (the summer of 1535) and the commissioning of the series (1546), the agreement to produce the tapestries (1548), and their actual manufacture (1550–1553). The key question is why there was a delay of over ten years in commissioning the painter Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen (1500–1559) to produce the cartoons, when this artist, in the company of the chronicler Alonso de Santa Cruz (1505–1572) among others, had travelled as part of the military expedition led by Charles V in order to make the necessary notes and drawings to produce a series of images.12 However, these initial images need not have been the cartoons for the later tapestries, which would commemorate and serve as propaganda, an event that soon came to be presented as one of the great imperial victories.

What is certain, nonetheless, is that from 1535 to 1546 the court of Charles V, despite significant approaches to international artists such as Titian, had yet to see the need for a compre...