- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Practices of cosmetic surgery have grown exponentially in recent years in both over-developed and developing worlds. What comprises cosmetic surgery has also changed, with a plethora of new procedures and an extraordinary rise of non-surgical operations. As the practices of cosmetic surgery have multiplied and diversified, so have feminist approaches to understanding them. For the first time leading feminist scholars including Susan Bordo, Kathy Davis, Vivian Sobchack and Kathryn Pauly Morgan, have been brought together in this comprehensive volume to reveal the complexity of feminist engagements with the phenomenon that still remains vastly more popular among women. Offering a diversity of theoretical, methodological and political approaches Cosmetic Surgery: A Feminist Primer presents not only the latest, cutting-edge research in this field but a challenging and unique approach to the issue that will be of key interest to researchers across the social sciences and humanities.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cosmetic Surgery by Cressida J. Heyes, Meredith Jones,Cressida J. Heyes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Antropologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Scienze socialiSubtopic

Antropologia

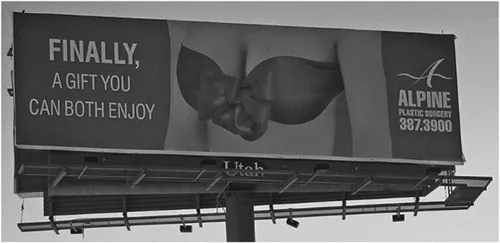

Figure 1.1 “Finally, a gift you can both enjoy”

Chapter 1

Cosmetic Surgery in the Age of Gender

We’re watching a clip from a TV documentary about cosmetic surgery on YouTube.1 It introduces Toni Wildish, 28-year-old mother of four, part-time shop assistant, and aspiring glamour model. Toni went to Prague as a cosmetic surgery tourist after determining that she couldn’t afford breast implants in the UK. The majority of the YouTube clip is a hand-held video diary made by Toni and her friend Claire, who accompanies her for moral support. They shriek and joke to camera, and Toni flashes her pre-op B-cup breasts; they seem to be having an exciting time, albeit that the shots of their cheap hotel room reveal it to be “very dark and dingy and a bit spooky.” Visiting the Czech surgeon, it’s immediately clear that he and Toni are not on the same page about the size and shape of her proposed implants. Toni rejects the first implant she’s shown, saying “oh that’s too natural, oh I don’t want them … Let me show you, I’ve brought my pictures … I want them so they’re really round.” She pulls out a file of images of Jordan (Katie Price)—the C-grade British celebrity well known for her huge augmented bosom—and the surgeon tries to suggest that her breasts’ very spherical look is created by an uplift bra. But Toni is one step ahead of him. She whips out her mobile phone, on which she has a photo of Jordan, topless—the massive breasts clearly standing independent of a bra. The surgeon is appalled, and declares in awkward English, “Oh, that’s horrible! I refuse to do something like that!” Later, in a talking head for the documentary, Toni says, “He was standing his ground, not giving me what I wanted. And I’d been told [by the medical tourism company that organized the trip] I could have what I wanted. And, well, I was just extremely let down.” Toni and the surgeon eventually compromise, but Toni still gets F-cup breasts, round and high on her chest, with nothing “too natural” about them. After the surgery she jumps up and down in her hotel room, hamming for the camcorder, declaring triumphantly, “They don’t move!”

When feminists first began thinking and writing about cosmetic surgery some twenty years ago, the state of affairs they confronted was dramatically different to the one described above. The conglomeration of global, media, technological, and aesthetic conditions that forms the backdrop to Toni Wildish’s story was the stuff of science fiction. Cosmetic surgery recipients were patients, not consumers; their desires were pathologized and people seeking cosmetic surgery were often secretive and ashamed. Talking about one’s surgery—let alone videoing it for global access—would have been both technically impossible and socially deviant. So Toni’s video story is a new kind of narrative, told via a new kind of medium in a new set of global circumstances, and it demonstrates significant changes in how cosmetic surgery is now chosen, undertaken and received.

In contrast, Carole Spitzack’s classic 1988 article “The Confession Mirror” (the first feminist publication on cosmetic surgery in English we know of) describes a very different visit to a cosmetic surgeon. Spitzack is asked to account for her “disease” to an expert who is completely authoritative, and who aspires to make her look more “natural.” It is imperative that her surgical outcome be subtle—even undetectable—as having been achieved through surgery. She is made abject, and must rely on the surgeon as her sole source of information about the technical and aesthetic possibilities for her body. Her experience is localized not only within her own country of residence, but even within the sanctum of the clinic and the context of her relationship with the surgeon.

The differences between Spitzack’s 1980’s foray into the secret world of “the confession mirror” and Wildish’s 2007 highly public surgical holiday highlight two issues that have been key to the formation of this volume: first, the landscape for feminists concerned to articulate cultural critique of cosmetic surgery has changed radically during the last twenty years, and political commitments or research methodologies that might have been a good match for the cosmetic surgical scene in 1988 may not suffice in 2008. Second, cosmetic surgery is far from being a parochial topic of limited political and ethical significance. There is increasing scholarly interest in it accompanied by intense popular fascination. It occurs at and highlights the intersection of tremendously complex and significant social trends concerning the body, gender, psyche, medical practice and ethics, globalization, aesthetic ideologies, and both communication and medical technologies. Indeed, cosmetic surgery is among the most interdisciplinary of topics and thus feminist analysis needs to start from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. So, represented in this volume are philosophers, sociologists, film studies theorists, cultural studies theorists, anthropologists, and those working in medical humanities.

Landscapes of cosmetic surgery are undergoing rapid change. For every newly touted technique (from silicone buttock implants to “combo packages” of Botox, Restylane, and laser resurfacing), and for every newly created media product (from shock-horror documentaries to award-winning television dramas like Nip/ Tuck) there could be a corresponding new feminist examination and approach. This is perhaps all the more reason to gather together the best “early” feminist writing about cosmetic surgery. We reprint excerpts from the work of four well-known feminist critics of cosmetic surgery—Susan Bordo (1993 and 1997), Kathy Davis (the earliest work she draws upon for this piece is from 1995), Kathryn Pauly Morgan (1991), and Vivian Sobchack (1999). We wanted to reproduce these “classics” while also recognizing that the world of cosmetic surgery has changed since they were first published, so we asked each author to revisit her original analysis to revise or comment upon her earlier perspective. While these chapters may be familiar to readers who have followed feminist critique of cosmetic surgery for some time (although the authors’ updates may provide some surprises), they provide vital orientation for readers beginning to look at the worlds of cosmetic surgery and the ways in which feminist scholarship has approached them. They are a tacit background against which more recent writing can be understood. The majority of the volume consists of newly commissioned work that takes on the feminist challenge of understanding the very complex shifting landscape of cosmetic surgery in its contemporary modes. The feminist literature on cosmetic surgery is not yet large and is dispersed among very diverse journals or contained in books oriented around other topics, and so feminists have been relatively disconnected from an ongoing scholarly conversation on the topic. This volume thus seeks to gather together and represent the existing field while also starting new feminist dialogues about cosmetic surgery.

Cosmetic Surgery in “the Age of Gender”

Medical techniques on which much cosmetic surgery is based emerged in the years following World War I, as male soldiers returned from the front with new kinds of injury (Haiken 1997: esp. 29–43, Gilman 1999a: esp. 157–68). The contemporary field of “plastic” surgery—intervention aimed at restoring the normal configuration of the body’s soft tissues—made its most rapid progress in response to these burns and wounds (perhaps especially of the face, as artist Paddy Hartley has demonstrated with his moving Project Façade2). Thus the distinction between reconstructive and cosmetic surgery emerged—the former, as the name suggests, restoring a body’s “normal” appearance or functioning after injury or so-called congenital defect, with the latter enhancing a body already taken to fall within “normal” parameters. Feminists have by and large accepted this distinction, and have limited their political critique to cosmetic procedures while implicitly accepting that reconstructive surgery—including that aimed solely at improving appearance (such as birthmark or scar revision)—is fully justified. However, a number of essays in this volume question these distinctions and examine the blurry boundaries between them.

In the modern history of cosmetic surgery, the first written account of a face-lift is dated 1901; breast augmentation dates back to risky injections of—briefly—paraffin, followed by a longer postwar period of experimentation with liquid silicone (Haiken 1997: 235–55); liposuction was invented in 1974 and has become increasingly popular since the 1980s. Since at least the 1950s, women have overwhelmingly been the target consumers for cosmetic surgery, while men have practiced it: in 2007, 91 percent of all cosmetic surgical procedures in North America were performed on women, while eight out of nine cosmetic surgeons are men. Furthermore, these women have been mostly white: in 2007, 76 percent of cosmetic surgical procedures in North America were performed on “Caucasian” patients.3 Historically speaking, this feminization of cosmetic surgery will probably be short-lived: in the longue durée cosmetic surgery may be, as Sander Gilman (1999a: esp. 31–6) has argued, more implicated with ethnicity and national belonging than with gender, while statistical trends indicate that a steadily increasing proportion of recipients are men as well as non-white. New procedures continue to be developed, and there has been an explosive growth in the number and type of cosmetic surgeries performed, in new national markets and among more diverse class, gender, ethnic, and age groups.

The work in this volume thus responds to the “age of gender” in cosmetic surgery—our play between gender and chronology is intentional here—while at the same time illustrating a more general trajectory in feminist attitudes to bodies. Thus it demonstrates how a big picture analysis in which body-transforming practices are understood as top-down pressures on women to conform to patriarchal ideals is giving way to the more fine-grained and multi-factoral analyses that are required to understand contemporary constraints and incitements. Recent feminist research on cosmetic surgery (Davis’s work is a notable older exception) has begun to interview and engage with a wide range of cosmetic surgery recipients through interviews and participant observation, deploying empirically grounded ethnographic methods: Debra Gimlin, for example, has found that, far from working on “body projects” in voluntarily self-conscious ways, women use cosmetic surgery as a way of dealing with the unwanted intrusion of the body into consciousness (2006), and that narrative tactics for explaining and justifying the decision to have cosmetic surgery vary by national context (2007).

The epistemic and ethical challenge of interpreting these self-justifications is, however, enormous. Cosmetic surgery has always had a complex relationship to psychology: since it cannot be justified on the basis of physical medical need, it must be justified in relation to the patient’s own desires. Elizabeth Haiken argues that in the US cosmetic surgery finds an early rationale in the “inferiority complex”—a syndrome first mooted by Austrian psychologist Alfred Adler in the 1910s (Haiken 1997: esp. 108–30; see also Gilman 1997: 263–65).4 Most Americans, Haiken implies, needed little more than a label to invoke the inferiority complex as a justification for numerous practices of self-improvement, and it enjoyed a significant vogue in media and advertising—and in selling the services of cosmetic surgeons (Haiken 1997: 111–23). Because the concept was vague and relative to the patient’s perception of her own psychology, surgeons could more easily justify intervention on the basis of psychic need. The individual stipulated of herself that she had an inferiority complex (a claim that could not be disproved), which she attributed (if she hoped to get cosmetic surgery) to a bodily defect. Thus, cosmetic surgery advertising both called forth the self-diagnosis while at the same time surgeons were quick to deny any psychiatric expertise that might actually necessitate psychological selection procedures. Against this background it is a short distance to justifying cosmetic surgical intervention whenever the patient makes a convincing enough case, and the surgeon believes that risk of a negative outcome (whether physical, psychological, or legal) is low enough.

This dynamic continues today, although the language of the inferiority complex has fallen away. As Cressida Heyes (2007a) has pointed out, the growing body of literature on the sequelae of cosmetic surgery is far from showing that recipients consistently experience positive, long-term psychological benefits. As we might expect, some people are very happy with surgical results and have no regrets, while others are deeply disappointed (even with a technically “good” outcome) and feel more damaged by surgery than by their initial dissatisfaction. Some return for more surgeries—a practice both encouraged by surgeons (who, like any businessmen, need repeat customers), and treated with some suspicion as evidence of addiction or dysmorphia (not least because the returning cosmetic surgery patient may be more likely to complain or sue) (see Kuczynski 2006, Pitts-Taylor 2007). Toni Wildish had a life-threatening experience with post-surgical infection, yet in a follow-up cameo she says that she plans to have even larger, rounder breast implants to achieve the “Jordan” look, as well as facial cosmetic surgeries. Here again, many surgeons’ expectations of the compliant, normalized “patient” who wants a so-called natural, feminine appearance achieved through a conservative procedure may be thwarted by contemporary clients who want extreme results, total transformation, and who treat their surgeon as a service provider whom they expect to acquiesce to their demands. This new psychology and the way it transforms client-surgeon relations reaches its limit in the extreme cosmetic surgery practitioner—those public figures who use surgery to make statements far removed from any conventional presentation of a beautiful body. Whether, as in Orlan’s case, the surgeries are used to make philosophical and visual aesthetic statements,5 or, as for Michael Jackson or Jocelyn Wildenstein, they produce a kind of mythical, monstrous cyborg (Jones 2008) whose political or aesthetic values are opaque, these celebrities disrupt the historical stereotype of the normatively feminine cosmetic surgery recipient who has any kind of “inferiority complex.”

There is another limit in the practice of “rogue” cosmetic procedures—those undertaken without medical supervision (and sometimes outside the law) by individuals who could not afford or would not be permitted access to medically sanctioned procedures. For example, Don Kulick describes how Brazilian transgendered prostitutes inject liters of liquid silicone into their bodies to achieve a normative form (Kulick 1998). Since his fieldwork the number of “minimally invasive” procedures available and their increasing popularity has spurred a global black market of unlicensed or unqualified practitioners offering cheap and quick “salon” services, sometimes using knock-off or non-medical injectables, while some are willing to undertake more invasive surgeries such as liposuction (see Singer 2006). This emergent market has barely been explored by any researchers, including feminists.

Part 1: Revisiting Feminist Critique

Understanding why so many people—most of them women—are attracted to cosmetic surgery to alter their “normal” appearance is a key question for feminists, who have not long had serious scholarship on the personal narratives of diverse constituencies of cosmetic surgery recipients to draw on. When we started work on this volume we imagined we would find an early feminist literature that was quick to see women who have cosmetic surgery as either vain social strivers, or as victims of a patriarchal beauty system. These attitudes may indeed have had a heyday in unpublished feminist conversations—and in the anomalous but persistent feminist moments that surface in popular representations of cosmetic surgery. Certainly when Kathy Davis describes this dominant perspective—in which cosmetic surgery is “unanimously regarded as not only dangerous to women’s health, but demeaning and disempowering”—she identifies a common belief, one held not only by self-described feminists. However, we have found that the feminist literature, on review, has actually always evinced a certain flexibility and curiosity about what cosmetic surgery might mean to individuals, and how that meaning might be understood as informing and being informed by a larger social context. Although different feminist theoretical models and disciplinary styles place different epistemic emphasis on women’s narratives (and use different interpretive strategies to theorize them), feminist scholarship is marked by a consistent interest in the reasons that cosmetic surgery recipients give for their surgeries.

Here in Part 1 Susan Bordo’s “Twenty Years in the Twilight Zone” comprises parts of her germinal essays “Material Girl” (1993) and “Braveheart, Babe, and the Contemporary Body” (1997), together with a brief 2008 update. Bordo is, recall, critical of the “postmodern imagination of human freedom from bodily determination”—especially in its pop cultural moments—for the way it denies the materiality of the flesh and levels political critique. In these selections she reminds us of how defect is not only corrected but also created by the economic and technological engine that carries us along, generating ever more impossible images. In her update, Bordo is pessimistic about the possibility that cultural critique can have any impact on this process; this is an important reminder from a commentator with a long perspective ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Cosmetic Surgery in the Age of Gender

- PART 1: REVISITING FEMINIST CRITIQUE

- PART 2: REPRESENTING COSMETIC SURGERY

- PART 3: BOUNDARIES AND NETWORKS

- PART 4: AMBIVALENT VOICES

- Index