- 182 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

As Ruskin suggests in his Seven Lamps of Architecture: "We may live without [architecture], and worship without her, but we cannot remember without her." We remember best when we experience an event in a place. But what happens when we leave that place, or that place no longer exists? This book addresses the relationship between memory and place and asks how architecture captures and triggers memory. It explores how architecture exists as a material object and how it registers as a place that we come to remember beyond the physical site itself. It questions what architecture is in the broadest sense, assuming that it is not simply buildings. Rather, architecture is considered to be the mapping of physical, mental or emotional space. The idea that we are all architects in some measure - as we actively organize and select pathways and markers within space - is central to this book's premise. Each chapter provides a different example of the manifold ways in which the physical place of architecture is curated by the architecture in our "mental" space: our imaginary toolbox when we think of a place and look at a photograph, or visit a site and describe it later or send a postcard. By connecting architecture with other disciplines such as geography, visual culture, sociology, and urban studies, as well as the fine and performing arts, this book puts forward the idea that a conversation about architecture is not exclusively about formal, isolated buildings, but instead must be deepened and broadened as spatialized visualizations and experiences of place.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Losing Site by Shelley Hornstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Marking Site: Walter Benjamin was Here

Pivotal to a discussion of architecture, memory and place is the importance of our material world. That we have materiality is no small factor in evaluating the role it plays in our lives. Let me begin with a discussion of the nature of making physical a place, and at the same time, what it means to possibly know a place, physically. Portbou is a remote town on the Costa Brava, at the northeastern edge of Spain. An active border-crossing before Europe became unified, Portbou is now a sleepy village. The coastline that traces both sides of the French-Spanish border is bare and mountainous, rugged and untamed. Whitewashed villages lodged between cliffs lace the edge of the sea from Cap Creus to Cap Béar, epitomizing maritime beauty while they conceal the disquiet of history. Close by, in the tunnel, under what was the border until 1995, a change of trains used to be required because of the gauge difference between French and Spanish trains. During World War II, endless delays were caused by searches conducted while travellers disembarked and re-boarded at the border crossing.1 Travel and, ultimately, destiny, were suspended. This place has shifted from being a border town to one that no longer has a frontier function, but carries the formidable weight of being both a fishing village with a quiet beach, and the place of Walter Benjamin’s death. Switches and whistles, flotsam sprays, whirling eddies and winds animate the simplicity and deceptive calm of this landscape with its history of train crossings and escape. Portbou is most familiar to those who know the story of Benjamin’s history there, and for those who travel to pay tribute to the philosopher at his memorial place. On a promontory at the tip of the extended arms of the cove, as a prelude to the town’s cemetery is where Passages, Homage to Walter Benjamin (1990–1994) by Dani Karavan begins. In a letter to Jean Selz, the philosopher and friend of Benjamin, Theodor Adorno wrote of what he was told about Benjamin’s last hours:

We think that it was 26 September 1940. Benjamin had crossed over the Pyrenees with a small group of emigrants to take refuge in Spain. This group was intercepted at Portbou by Spanish police, who told them that they would be sent back to Vichy the next day. In the night, Benjamin swallowed a massive dose of sleeping pills and opposed the care they offered him.2

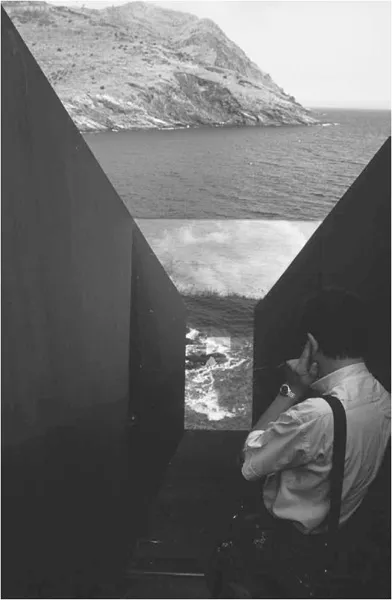

1.1 Dani Karavan, Passages, 1994, Portbou. Credit: Shelley Hornstein.

Karavan’s Passages attempts to spatialize the conjunction of Benjamin’s life and death. It is a memorial that measures space and time. Out of what appear to be arbitrarily placed objects in the landscape, order emerges. Passages is, quite simply, if not reductively, an appointment with nature. Consonant with the issues Benjamin addresses in his writings – on memory, architecture, political and intellectual history, a topic to which I will return later – the memorial is composed of an assemblage of props or sensorial aids that heighten the sounds, sights, touch, and even the smell of nature. It not only poetically explores his writings, but bespeaks his fate.

How might we rethink commemorative sites in the light of the two major challenges facing the making of memorials? Commonly considered permanent installations to mark the geographic location of an event in history and/or memory – not always the same – memorials face challenges at a time when we are wont to mark, honour or celebrate history. During this peculiar period of overmemorialization, even obsession, as Huyssen has called it,3 with erecting or creating or rethinking memorials, how can we achieve something significant without overdetermining the project and numbing its relevance to those who will explore it?

With Passages, Karavan diagnoses the complexities of commemoration in a culture that is preoccupied with memorials and sites of memory. He prescribes a monument that heightens consideration of place, that is, the natural and built environment. Yet, by virtue of its remote location, this place will be seen only by a few. A monument, after all, is built for its constituents: those for whom it holds meaning. But who are its constituents? If it aims to reach out to those not affected directly by that history or memory, it can only do so as an art object. Pragmatically, this can be a good thing, luring tourists in order to educate them indirectly through the art itself about the tragedies of history. The monument then becomes a symbol, that is, with no relationship to that which it signifies, but needing to be learned in order to become convention, as does language. Therefore, Karavan distributes the pieces of this memorial as stepping stones for pulling together the ideas necessary to consider the whole. The whole, summed up by these parts scattered in this place. And for Karavan, this place matters and is, without doubt, the monument’s raison d’être. Erecting a monument on the site of a tragedy means erecting a monument for a community with a shared history and memory or a desire to pay tribute to that history. The shared history and memory of Walter Benjamin are both local to Portbou, and international. But given its remote location, even its near-isolation, will this buried monument be effective with no visitors? Karavan feeds off the need to address remoteness and thus turns the monument back to nature.

In order to claim the site of the monument for the memorial, Karavan selects rough, cold, industrial materials: glass and rusting Corten steel that alert us to the ideas that he introduces. He propels us into a contract with nature, which demands – through our varying positions and perspectives – that we respect what we hear and see and feel. Instead of controlling the vistas, we subordinate ourselves to them and relinquish the need to colonize and appropriate what we hold within our senses. Karavan’s work guides us to the heart of the project: place as the here and now, place as far from us, place as the ultimate memory marker. But because place counts before all else, ‘being there’, experiencing it in situ, is a prerequisite.

‘Being there’ is, however, a circumstance of privilege: a privilege of knowledge about Benjamin who, after all, is not a household name; of the history of his escape plans through Spain, his death at Portbou, and of the existence of the memorial. Perhaps this privileged knowledge constitutes what Jay Winter calls ‘memory activists’ or ‘fictive kin’ who, as he suggests, are those in

… unified groups, [who are] bonded not by blood but by experience. They share the imprint of history on their lives. They work, quarrel, and endure together; they support each other. At such times, their bonds are sufficiently strong to allow us to call them ‘fictive kin’. Indeed, these ‘fictive kinship groups’ are key agents of remembrance.4

In order to remember effectively, one must ‘shrink and focus’ from the national scale of remembering an event to the ‘particular and ordinary’, that is, aim to localize through smaller groups of people and specifically in towns where the direct rapport with the site takes effect.5 Commemoration can only begin by working through shared, communal memory, but according to Winter’s definition, the group in question would be those residents of Portbou who were in some way connected with the French and Spanish border patrols. However, they are, at least for now, the silent group. Conversely, the active group, according to Winter, is composed of those who come to honour the work of the philosopher and to support each other because of their implicit connections with the circumstances surrounding his death, rather than to quarrel.

Like a spear piercing the road to reappear on the overhanging cliff, a wide, square, rusty, beam-like tunnel marks the beginning of Karavan’s Passages. At first dark and covered and later open to the sky, this is actually a steep, confining stairwell, 30m long, that invites but simultaneously terrifies as it plunges to the sea. Our sightline is forced to confront the turbulence of the swirling waters. Karavan tampers with our equilibrium as we become unhinged from the stable ground. In this chute we are provoked to consider performing our own possible deaths, but stop short before being hurled into the sea. Therefore we tread gingerly down these steep steps until we meet the glass wall that prevents our further descent. Etched in the glass is an epigraph by Benjamin that poetically expresses his thoughts about returning to the past by way of a shock in the present, while underscoring the dangers of dwelling on him alone: ‘It is more arduous to honour the memory of the nameless than that of the renowned. Historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless’6

Our task of remembrance, as Karavan suggests through Benjamin’s words, is a continuing project, always linked to others and to places that are never separate or distinct. Our return to the top of the stairwell brings us face-to-face with those larger connections as we confront a tombstone-like construction made of rocks from the adjacent pathway across the road. Even further afield, tucked behind the edge of the existing cemetery, are five Corten stairs that create a viewing station to a solitary olive tree (fig. 5). Further up the harsh trail around the cemetery wall is yet another environmental piece that reads as a found object: a low cube in the centre of a square, rusty platform (fig. 6). Is this a seat for mediation? A bolt anchoring the platform? A gravestone? A socle for the traditional sculpture that Karavan’s work displaces? Karavan’s memorial exists in the visual, tactile and aural realms. He takes as his commemorative object the evidentiary site, and intentionally inserts manufactured objects into the landscape. He carves imaginary potential pathways for new geographies in the rugged surroundings. Building on the dual challenges of how to make a memorial bear meaning in a period after the obsession with memorialization and the haunting taboo against representation post-Holocaust, Karavan’s Passages punctuates the earth at multiple strategic points to amplify nature and shape space. He is determined to fashion our movements although he refuses to allow the monument to act as a narrative guide. Instead he resists sequentiality in an experiment with architecture that burrows into and erupts out of the site; it disappears and reappears, effacing itself in order that we may fill the continuum. It underscores the immediate topography by reaching out to physical and imagined places beyond its own physicality, evacuating itself from its place, while, ironically being both in this place and beyond it. By our movements in and around the site, we activate the ground of history and conjoin the here and there. It is very true that in this place, nature itself, as Karavan explains in his sketchbook, is actually telling the tragedy of Walter Benjamin, but only, I would argue, because Karavan calls it to our attention.7 We in turn read the tragedy by the cues that he provides, cues comparable to Le Corbusier’s framed ‘window’ onto the landscape of Poissy in his Villa Savoye, or Jan van Eyck’s painted vista seen from the loggia in The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (1433–1434; Louvre), both of which provide viewing boxes for otherwise ignored landscapes.

Karavan’s small, unassuming, self-effacing yet declaratory piece attracts a handful of visitors annually to make the pilgrimage. The monument, then, is a pivotal addition for Portbou as it forges a link to the past for its residents while possibly awakening a collective responsibility. For the tourist economy the town is now the memory theatre for the itinerant performance of visitors. They come to pay homage to Benjamin, or reconcile the past, and for this the monument serves as tangible proof that history took place here. Karavan acknowledges the complexity of his mission, but his motives are clear: even if only a few pilgrims actually reach the site, he aims for the widest and largest possible public. He chooses to accentuate the deceptive serenity of nature, as he has in many other works, thereby steadfastly grabbing our attention. Our thoughts turn to Benjamin’s death and his larger meditations on history, memory, and trauma.

As if to suggest peacefulness and stability, the memorial seems at first to be anchored in one physical place, while it slowly reveals its inner energy. It devolves, dismantles itself and becomes unfixed, appearing infinitely moveable in the landscape and in the imaginary. Karavan’s Passages, while anchored firmly in the soil, seems to be severed, with its own parts scattered. Furthermore, it severs the ground by altering its own and the place’s topography. No longer keeper of its own shape, the monument reaches across the overhanging ledge to an immeasurable region not defined by borders. This ‘smooth’ space echoes the ‘nomadic’ space of Deleuze and Guattari, who understand smooth space structure as contingent upon its situation. Inspired by Pierre Boulez who coined the terms with regard to music, smooth music allows for irregularity of movement. Striated music, in contrast, follows an ordered pattern. Smooth space ‘has no homogeneity … and the linking of proximities is effected independently of any determined path … Smooth space is wedded to a very particular type of multiplicity: nonmeric, acentered, rhizomatic multiplicities that occupy space without “counting” it and “can be explored only by legwork.”’8

Nomadic space is not subject to directional movement or narrative: it is defined by mobility, and mobility – ironically as it abolishes fixed placement – can arguably be defined by its relationship to place. Movement follows a trajectory – a mobility from and to a place – rather than a defined route.9 In this way the monument speaks of the arbitrary nature of borders.

Relays move across the physical and visible landscape with no specific direction. The only guidance is provided by sounds echoing in the cove. Passages is connected geographically with other sites that Benjamin knew: Naples, Paris, Marseilles, and Berlin. Spatial and imagined places transport us to recall Benjamin through his writings and the almost mythologized story of his journey across the Pyrenees to Portbou, where he spent his last ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Marking Site: Walter Benjamin was Here

- 2 Memorializing Site: On the Grounds of History

- 3 Transporting Sites: Israel, Postcards and Nation-Building

- 4 Destroyed Sites: Places and Things Inside Out

- 5 Curating Site: Museums, Itineraries and Networks Beyond Borders

- 6 Erasing Sites: Spies on the Other Side of the Full Moon

- 7 Finding Site

- Bibliography

- Index