eBook - ePub

From Archaeology to Spectacle in Victorian Britain

The Case of Assyria, 1845-1854

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In his examination of the excavation of ancient Assyria by Austen Henry Layard, Shawn Malley reveals how, by whom, and for what reasons the stones of Assyria were deployed during a brief but remarkably intense period of archaeological activity in the mid-nineteenth century. His book encompasses the archaeological practices and representations that originated in Layard's excavations, radiated outward by way of the British Museum and Layard's best-selling Nineveh and Its Remains (1849), and were then dispersed into the public domain of popular amusements. That the stones of Assyria resonated in debates far beyond the interests of religious and scientific groups is apparent in the prevalence of poetry, exhibitions, plays, and dioramas inspired by the excavation. Of particular note, correspondence involving high-ranking diplomatic personnel and museum officials demonstrates that the 'treasures' brought home to fill the British Museum served not only as signs of symbolic conquest, but also as covert means for extending Britain's political and economic influence in the Near East. Malley takes up issues of class and influence to show how the middle-class Layard's celebrity status both advanced and threatened aristocratic values. Tellingly, the excavations prompted disturbing questions about the perils of imperial rule that framed discussions of the social and political conditions which brought England to the brink of revolution in 1848 and resurfaced with a vengeance during the Crimean crisis. In the provocative conclusion of this meticulously documented and suggestive book, Malley points toward the striking parallels between the history of Britain's imperial investment in Mesopotamia and the contemporary geopolitical uses and abuses of Assyrian antiquity in post-invasion Iraq.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Layard Enterprise: An Archaeology of Informal Imperialism

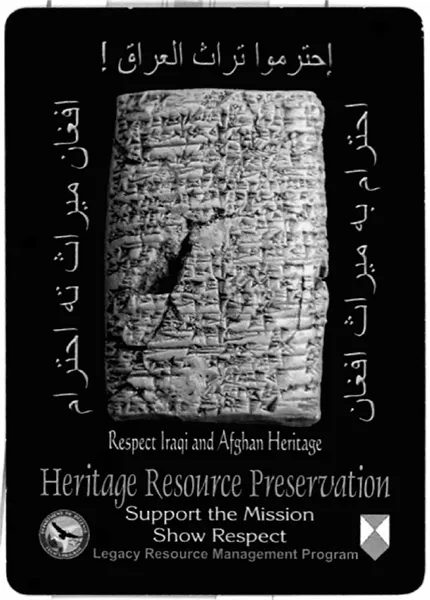

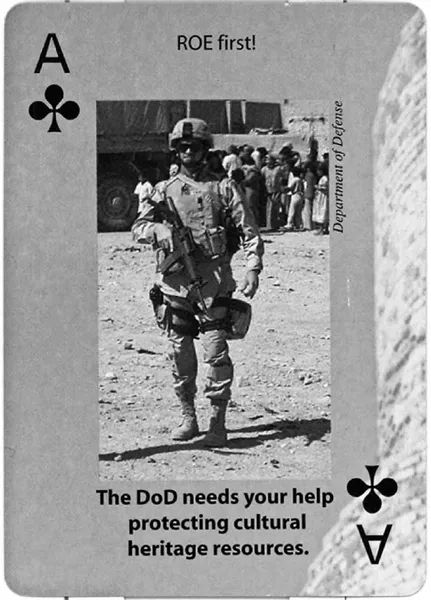

With the dust settling on Operation Iraqi Freedom, the US Army 4th Psychological Operations Group developed for the occupation forces produced a special deck of playing cards featuring head shots of the most-wanted Iraqi regime officials. Saddam Hussein figures prominently as the Ace of Spades. Popular with the troops, another deck was issued in the autumn of 2007, but this time representing some of Iraq’s and Afghanistan’s archaeological sites (Figure 1.1). This was part of the Department of Defense’s Legacy Resource Management Program initiative to teach soldiers about handling sensitive archaeological materials and their value to local and international communities. The cards remind the troops that artifacts are not souvenirs and that archaeological sites should not be used for military emplacements, as exemplified by the construction of a helicopter pad on the ruins of Babylon in April of 2003.1 Each card weds an archaeological image with helpful information or an inspirational slogan: “Drive around—not over—archaeological sites”; “No graffiti! Defacing walls or ruins with spray paint or other materials is disrespectful and counterproductive to the Mission”; “When possible, fill sand bags with ‘clean’ earth—earth that is free of manmade objects, including broken pieces that may seem insignificant”; “Helicopter rotor wash can damage archaeological sites. Locate your LZs [landing zones] a safe distance away from known sites.” Depicting soldiers during military and recreational activities, the cards dramatize the central objective of the deck: in the words of Fort Drum’s Cultural Resources Program Manager Dr. Laurie Rush, “to balance stewardship responsibility with mission support.”2 The Ace of Clubs, for instance, interpellates the fighting man as a defender of both Iraq and Iraqi heritage. “The DoD needs your help protecting cultural heritage resources” (Figure 1.2). He stands resolute and alone in the foreground. Civilians cluster behind a supply truck in the background.

Fig. 1.1 Archaeological Awareness Playing Card (verso)

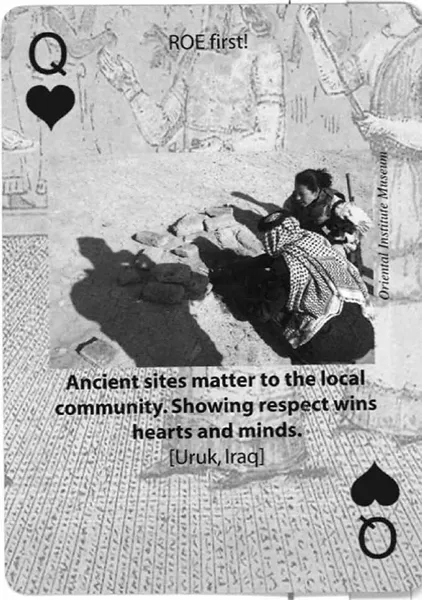

The cards’ imagery is indicative of the fundamental shift in objectives between Operations Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom: protracted military occupation necessitates Iraqi cooperation and collaboration. The Queen of Hearts locates this objective firmly in the rhetoric of archaeological stewardship (Figure 1.3). Divested of her helmet but well armed, she is shown some inscribed bricks by a civilian whose back is turned to the camera. “Ancient sites matter to the local community. Showing respect wins hearts and minds.” Receiving the gift of antiquity from the faceless native, the Queen of Hearts emerges as the patron of the deck’s core message: Iraq is the “Cradle of Civilization” and its artifacts are the shared property of the West. Assuming a reverent stance before antiquity, soldiers now belong ideologically and culturally to the landscape they physically occupy. Another card advises the soldier to “Respect monuments whenever possible. They are part of our collective cultural history.” In another, a soldier addresses schoolchildren: “The main goal of archaeology is to understand the past—your past.” Scripture is even invoked: “Ancient Iraqi heritage is part of your heritage. It is believed that Jonah of the Bible is buried here [Nabi Yunis Mosque in Mosul, Iraq].” In several cases, American iconography overlays Iraq’s. Guarding the Statue of Liberty, the Jack of Diamonds defends American values and interests in Iraq: “How would we feel if someone destroyed her torch?” The Torch of Freedom—itself a gift of political solidarity—is extended to the Iraqi people through archaeological stewardship. Drawn into a display of American republicanism, archaeology supports the larger mission objectives of implanting and protecting Iraq’s nascent free-market democracy.

A related theme is theft, a sensitive issue in the wake of the infamous three-day looting and vandalism of the Iraq Museum in April 2003.3 This episode was especially troubling for the archaeological community, because the US Department of Defense was urged by a leading group of archaeologists prior to the war to protect antiquities in the major museums and archaeological sites from looting.4 Clearly represented as “collateral damage” in military operations—“Museums are also victims of conflict and need protection when possible”—the cards are a tacit admission of culpability and a gesture of reconciliation. The Queen of Clubs, for instance, warns the soldier to “Remember! The buying and selling of antiquities is illegal and punishable under the Uniform Code of Military Justice.” We learn from the Eight of Diamonds that the “The Joint Interagency Task Force recovered more than 5,000 artifacts stolen from the Iraq Museum. The Mask of Warka was recovered by the 812th MP Company.” The cards carefully orchestrate this promise to value Iraq’s cultural heritage during the occupation by appealing to the military values of protection and heroism themselves. Once at war against the “freedom-hating” dictator, the soldier/archaeologist remains behind to guard the cultural legacy she has liberated for the Iraqi people. A new weapon in the war on terror, archaeology is for the American military a platform for defending the economic and neo-imperialist agendas fueling the mission to Iraq in the first place.5

Fig. 1.2 Ace of Clubs

Fig. 1.3 Queen of Hearts

But this of course is nothing new, for soldiers and archaeologists have dug into the same ground for over a century and a half. Consider a recent publication by archaeological historian Brian Fagan, Return to Babylon: Travelers, Archaeologists, and Monuments in Mesopotamia (University Press of Colorado, 2007). A revision of his 1979 book, the publication is timely, he relates, because “recent archaeological catastrophes in Iraq have kindled renewed interest in the long history of Mesopotamian archaeology.” His justifications for the new edition reveal much about the assumptions under which the book was published by a university press in the wake of the Second Gulf War. First, he defends the book’s narrative format on the grounds that his is a “narrative of discovery, not of intellectual trends, which are of less interest to general audiences.” The second justification takes the form of a qualified apology, that Austen Henry Layard and Émile Botta, the first Europeans to begin large-scale excavation in Mesopotamia, “were appalling excavators by today’s standards, but they placed the Assyrians firmly on the stage of world history.” Continuing the dramatic metaphor, Fagan, thirdly, ends his prefatory remarks by declaring, “This adventure story is replete with interesting characters, at present with a tragic ending but surely with hope for the future. The stage is set. Let the play begin!”6

My intent is not to question Return to Babylon as a source of information (nor, for that matter, the DoD’s efforts to limit damage to Iraq’s archaeological remains), rather, Fagan’s assumption that archaeology is an inherently and unquestionably noble and humanizing activity. Fagan ironically displaces the motives for his revision—the destruction of antiquities in wartime—into an adventure story. Contrary to his disclosure, intellectual trends are deeply entrenched in the narrative of discovery. Fagan’s plaintive conclusion that looters are “selling Iraq’s birthright and the cultural heritage of all humankind, which we all should collectively hold in trust for generations as yet unborn,”7 buries the complex and troubled history of East–West relations under the kind of comfortable humanist rhetoric adopted by the DoD for their playing card initiative. As a cornerstone of Western culture (Jonah is “ours,” too), Assyria is a world heritage site that we Westerners must be trusted to protect from the ignorance and greed of Iraqis, not to mention from our own bombs. What often goes unnoticed or unsaid in the popular understanding of archaeological activity is that the times and spaces of excavation activities themselves may impart contentious meanings to the objects displaced from the ground. So, too, the cozy narrative archaeological history, with its focus on “great men” like Schliemann of Troy, Evans of Knossos, Layard of Nineveh, and Woolley of Ur, requires radical reexamination in light of the institutional and cultural discourses their protagonists consciously and unconsciously promoted.8 Like the innocent image of Mesopotamia as the cradle of civilization and the 150-year-old program of stewardship it endorses, heroism itself is a historiographic mechanism that disguises the political motivations that threaten the survival of the artifacts themselves.9

Both the playing cards and Fagan’s history bring up and quickly bury tensions between archaeology as a supposedly disinterested study and archaeology as a profoundly polemical activity that is often involved in the location of conflicting identities in particular spaces. In their 2004 volume A Companion to Social Archaeology, Lynn Meskell and Robert Preucel argue that the Gulf Wars “underscore the intensely political nature of the archaeological enterprise.” The US-led military operation and the international outcry to looting and bombing of archaeological sites both express the entrenched view of the region as a precious repository of a world heritage “that requires control and management by Western experts and their respective governments.”10 Sensitive questions about archaeologists’ complicity with this paradigm of stewardship and their service of nationalist and imperialist agendas have never before been so widely circulated and theorized.11 For example, in Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology and Nation Building in Modern Iraq (2007), Magnus Bernhardsson characterizes the history of Mesopotamia in military terms, claiming that the “battle over Iraq’s historical artifacts was ultimately a struggle over Western involvement in the Middle East.”12 Blending images of stewardship, humanitarianism, and militarism, the DoD’s playing cards inherit a tradition of archaeological imperialism dating back to the European struggle for political influence in the failing Ottoman Empire.13

In this chapter I argue that the myth of archaeological stewardship needs to be historicized and problematized at its very birthplace. For the British, this begins with the myth of “Layard of Nineveh.” But as Fagan’s comments suggest, we are still reluctant to tarnish Layard’s legacy with politics. For instance, Frederick Fales and Bernard Hickey published in 1987 a collection of essays composed by leading authorities on Layard, including British Museum archaeologists Richard Barnett, Julian Reade, and Dominique Collon, art historian Judy Rudoe, Layard biographer Gordon Waterfield, constitutional historian Kenneth Bourne, and diplomat Sir Ashley Clarke.14 These essays constitute a watershed in Layard studies, for they represent the breadth of scholarly interest in Layard’s career as an archaeologist, art collector, politician, and diplomat. Unfortunately, the chronological rather than synchronic arrangement of the volume isolates these activities from each other, preventing critical scrutiny of their interconnections; consequently the collection is more an appreciation than a critical inquiry. More recently, Mogens Trolle Larsen’s 1996 monograph The Conquest of Assyria: Excavations in an Antique Land nostalgically compares Layard to the Hollywood action–adventure star Indiana Jones.15 As noted in the introduction, art historian Frederick Bohrer has begun challenging this image by situating nineteenth-century archaeological aesthetics within Orientalist discourse. Published in the year of the Iraq invasion, his book Orientalism and Visual Culture: Imagining Mesopotamia in Nineteenth-Century Europe negotiates the complex processes whereby Europeans have transformed material objects into exotic subjects, a process that is complicit, he argues, with ethnological rationalizations of European informal imperialism in the Middle East.

Bohrer provides a solid basis on which to review Layard himself as a rich site for unearthing the ideological work of Victorian archaeology within the politically charged atmosphere...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Opening the Layard Box

- 1 Layard Enterprise: An Archaeology of Informal Imperialism

- 2 Re-membering Assyria: The Case of the Bull and Lion

- 3 Theatre/Archaeology: Sardanapalus, 1853

- 4 In the Shadow of the Bull: Archaeology, War, Entropy

- 5 Precession of the Bull: Simulated Assyria

- Conclusion: Digging Up the Future: Assyria in Science Fiction

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access From Archaeology to Spectacle in Victorian Britain by Shawn Malley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.