eBook - ePub

Russia's Food Revolution

The Transformation of the Food System

Stephen K. Wegren

This is a test

Share book

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Russia's Food Revolution

The Transformation of the Food System

Stephen K. Wegren

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book analyzes the food revolution that has occurred in Russia since the late 1980s, documenting the transformation in systems of production, supply, distribution, and consumption. It examines the dominant actors in the food system; explores how the state regulates food; considers changes in patterns of food trade interactions with other states; and discusses how all this and changing habits of consumption have impacted consumers. It contrasts the grim food situation of 1980s and 1990swith the much better food situation that prevails at present and sets the food revolution in the context of the wider consumer revolution, which has affected fashion, consumer electronics, and other sectors of the economy.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Russia's Food Revolution an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Russia's Food Revolution by Stephen K. Wegren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Thinking about food revolutions

Imagine if it were possible to travel back in time to Moscow in 1990. You would find a grim food situation. In 1990, gross food production was not the primary problem, but the food distribution system had broken down and criminal elements were withholding food from cities. Even in the capital, consumers experienced chronic shortages of low-quality food. While no one was starving in the USSR, consumers could not expect to find beef, chicken, pork, or sausage on a regular basis. To ensure at least minimum consumption levels, food rationing was introduced in the winter of 1990 for the first time since World War II. Food coupons that were supposed to ensure access to a minimum supply of food were more times than not worthless because shelves were empty. Advisors to Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev told him that the country needed to import food and consumer goods to save perestroika, which had become unpopular with the Soviet people. Soviet Russia had not quite yet fully opened its trade borders, so Western foodstuffs were not widely available, although by 1990 the trickle had begun, at least in Moscow. Mostly, by 1990 the consumer experience was difficult and frustrating, entailing a daily grind to search for food. Distribution networks had deteriorated to the point that Gorbachev put the KGB in charge of food distribution in an attempt to ensure that food reached shelves in state stores. In terms of consumption, Soviet consumers were already tightening their belts and buying less food, due to emerging food inflation. While the government debated the extent to which food prices should remain regulated by the state, supply and demand decided the actual food prices that consumers paid. Households did more and more of their food shopping at urban markets, where selection and quality were better, but prices were five to ten times higher than in state stores. A small percentage of the population was able to take advantage of the nascent cooperative movement; most cooperative owners had migrated into the restaurant and café business. The prices at these coop-restaurants were prohibitively high and out of reach for the common consumer. The cooperative movement fed popular distaste for private entrepreneurs. In 1990 the first Western fast food appeared—McDonald’s and Pizza Hut—but the outlets were so few that their impact on the average consumer was negligible. The one and only McDonald’s in the Soviet Union opened in January 1990 in Moscow to enormously long lines, a reflection of demand for tasty food with reliable supply. A single meal would take up one-half or more of an average monthly salary.

The first decade of post-communism was hardly better. During the 1990s consumers’ real income contracted and food inflation raged. The country experienced mass poverty. A cruel cycle emerged: as household budgets became strained, consumers bought less food and ate less. Food demand fell. As demand declined, farms, which were already feeling the effects of reductions in state subsidies (despite a system of soft credits) and price scissors, curtailed food production. Lower domestic production helped retailers to keep food prices high and generated demand for imports, which, while usually of better quality, were also more expensive as the value of the ruble deteriorated. As the decade progressed, the “green shoots” of a capitalist consumer economy emerged, but the benefits were beyond the reach of most Russians. If during the 1980s consumers were concerned about where to find food, in the 1990s they were concerned with how to afford food.

Now imagine you could return to Moscow (or any large city) in 2019–2020. The food situation bears no resemblance to 1990. The present-day Russian consumer does not have to worry about food shortages, long lines, or empty shelves. Today, middle-class consumers’ wonder about which restaurant and which cuisine to try. During June 2019, I ate Russian fast food and Russian food at a traditional sit-down restaurant. I also ate Georgian, Uzbek, pizza, American fast food, hamburgers Russian style, sushi, Chinese, Nepalese, and Japanese. I visited a food mall and food courts in shopping centers in Moscow. I went to several beer gardens, including a craft-beer enterprise in Kostroma. I visited craft-cheese operations outside of Moscow and in the city of Kostroma. I visited food stores of different sizes operated by national and regional companies. In 2019, almost 13,000 restaurants and places to eat outside the home operated in Moscow alone, offering every type of cuisine imaginable, Russian and foreign, at every price level. Fast food restaurants of both Russian and foreign origin are found in every neighborhood and district. McDonald’s, the lone pioneer in 1990, operates more than 600 of its restaurants throughout Russia, extending into the Ural region and Siberia. McDonald’s now competes with numerous Russian fast food chains as well as other Western companies; together, the number of fast food restaurants in Russia is several thousand. Today, a typical Russian family may spend a Sunday at a mall and eat at food court that offers a variety of Russian, Asian, and Western cuisines.

Retail food shopping has been transformed. A consumer may choose from neighborhood food stores or supermarket chains. Shopping malls have food courts that offer a variety of Russian, Asian, and Western cuisines. Gigantic hypermarkets sell food as well as a wide selection of other household goods. Specialized food stores offer high-end imported food that caters to the wealthy. Outdoor food markets continue to operate but are no longer the primary source of food shopping for most families. Retail food chains operate their own supply chains from farm to storage to transportation to retail stores.

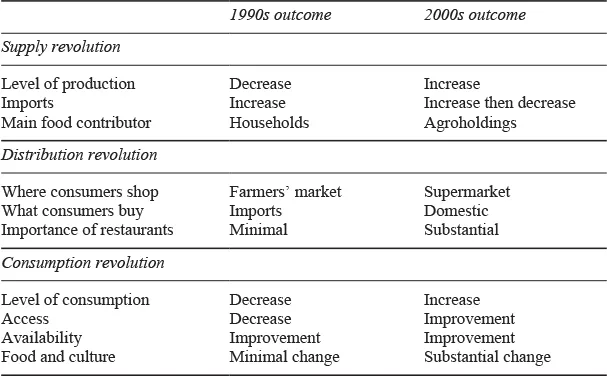

What has occurred since the fall of communism in Russia is not merely a transition, a term that implies some degree of continuity from the previous system. Instead, Russia has experienced a food revolution. A conceptualization of Russia’s food revolution model is presented in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Scheme of food revolution model

Note

a Level of consumption is measured by average per capita food consumption and daily caloric intake.

a Level of consumption is measured by average per capita food consumption and daily caloric intake.

Why did Russia experience a food revolution? There have been several important drivers. First, systemic economic change brought to the forefront new actors, new institutions, new policies, and new opportunities that were central to the food revolution. Second, changes in the economic and political environment facilitated new consumer expectations and demands. Russian consumers expected alternatives to Soviet-era long food lines, limited selection, and low-quality food products. Moreover, new consumer expectations and demands were derived from foreign travel, and access to foreign media and movies. Russian consumers learned of alternatives to food lines, limited selection, and low-quality products. They wanted better. They demanded better. In short, Russia’s food revolution is part and parcel of a broader consumption revolution in Russia. The consumption revolution is evidenced by higher spending on consumer durables and electronics for the home; the purchase of new apartments; the “dacha boom” outside of large cities; increased foreign travel; and the development of a car culture as witnessed by a significant increase in gasoline consumption and personal car ownership.1 Reflecting the rise of a car culture, suburban McDonald’s restaurants have drive-through pickup, similar to what happened in America in the 1950s with the rise of its car culture. The consumption revolution in Russia means that the average consumer today has more choice and better access to products of all types, not just food, than at any time in post-Soviet history.

A third driver was political change that liberalized the system, allowing access to foreign information and making foreign travel accessible to the masses. Russian travelers could see first-hand how people in Europe, America, and Asian nations shopped for food and ate. To be denied basic rights to food that other nations enjoyed may have been politically explosive. Political change also brought about a change in philosophy regarding the purpose and quality of life. No longer was the purpose of life to serve the Communist party and fight for communist causes, but rather to enjoy the pleasures of life, including different food experiences.

A fourth driver was an improvement in personal income and the investment environment; there cannot be a food revolution unless people have money to spend on food and unless entrepreneurs are willing and able to invest. Real per capita incomes increased by more than 11 percent per annum during 2001–2008, which in turn spurred increase demand for food. Increased demand opened up opportunities for investors to make money, and thus supermarkets began to populate the retail landscape and eating outside the home became more popular. Concomitant with a rise in per capita income, domestic agricultural production rebounded and the volume of imported food rose to 2013, both of which reflected increased demand and purchasing power. Furthermore, the investment climate improved. According to the Doing Business series published by the World Bank since 2004, Russia has improved significantly, ranking 28th out of 190 countries in 2019. The number of days taken to start a business declined from 36 days in 2004 to ten days in 2018; and the number of days to register a property decreased from 52 days in 2005 to 13 days in 2018.2

This book focuses on the transformation of Russia’s food system, but similar analysis could be applied to transformation in other spheres of consumer life as well. Several arguments are developed throughout this book. The first, and most important, is that a food revolution is part of the landscape that defines contemporary Russia. This food revolution distinguishes the contemporary food system from that in the 1980s and 1990s. The origins of this revolution may be traced to 2000–2001 and the rise of state capitalism in Russia under President Vladimir Putin. A food revolution is operationalized to encompasses food supply, food distribution, and food consumption. These variables were chosen because of their centrality to food systems and to food security.

A second argument is that although the food revolution is most pronounced in Moscow and other large cities, it is not restricted to large cities. In Chapters 4 and 5, I discuss some of my observations in medium-sized cities that reflect the food revolution there. Here, suffice it to note that enhanced con...