- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1991. "A photojournalist is a mixture of a cool, detached professional and a sensitive, involved citizen. The taking of pictures is much more than F-stops and shutter speeds. The printing of pictures is much more than chemical temperatures and contrast grades. The publishing of pictures is much more than cropping and size decisions. A photojournalist must always be aware that the technical aspects of the photographic process are not the primary concerns."

This book addresses ethics in photojournalism in depth, with sections on the philosophy in the discipline, on pictures of victims or disaster scenes, on privacy rights and on altering images. As important and interesting today as when it was first in print.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Photojournalism by Paul Martin Lester in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Merger of Photojournalism and Ethics

Civilization is a stream with banks. The stream is sometimes filled, with blood from people killing, stealing, shouting and doing things historians usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed, people build homes, make love, raise children, sing songs, write poetry. The story of civilization is the story of what happened on the banks. ...

-Will Durant

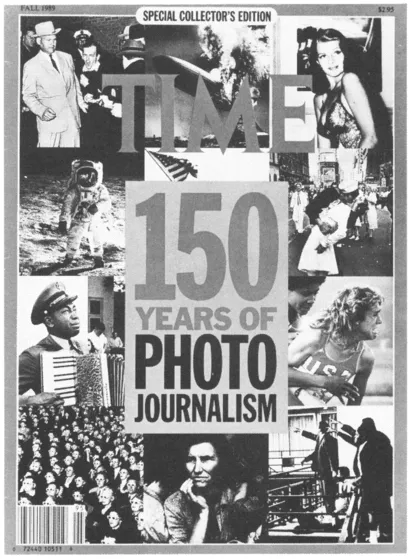

In a fitting tribute to the power and prevalence of photojournalism images, Time magazine recently produced the first issue in its history on a single topic with a single advertiser. Measured from the dual technological achievements announced in 1839 of Louis Daguerre's daguerreotype and Henry Talbot's calotype, the 150th year of photography has been celebrated throughout the world with gallery exhibitions and feature articles in all manner of media.

Life magazine, a publication responsible for photojournalism's rise in respect, published an anniversary issue titled, "150 Years of Photography: Pictures that Made a Difference" (1989). American Photographer (Squires, 1988), a magazine that regularly features works by newspaper and magazine photojournalists, devoted its cover and over 30 pages to the subject of photojournalism. Marianne Fulton (1989), associate curator of photographic collections at the International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, was the editor of a well-researched and richly illustrated book on photojournalism, Eyes of Time: Photojournalism in America.

Jim Dooley, photography editor and chief for the Long Island newspaper, Newsday, remarked that "newspaper photojournalism is in its heyday. It's going through a tremendous renewal" (cited in Fitzgerald, 1988, p. 35). Professor of Photojournalism at the University of Missouri, Bill Kuykendall, also feels that there is now a photojournalism renaissance. "I think there has been a rebirth," said Kuykendall, "of interest in candid ... photojournalism" (cited in Fitzgerald, 1988, p. 35).

Just as discussions of photojournalism have received an abundance of media treatment, professional ethics has also received widespread attention in magazines, books and from experts in the field (see Barrett, 1988; "Pentagon Probing," 1988; "What ever happened," 1987).

Ethical issues are hot topics in today's media-conscious society. Questions currently debated in formats that vary from newspaper articles to public forums broadcast on public television stations include: Is insider trading a result of greedy individuals or does it foretell a problem with the entire system of business? Are the temptations from profit motives too great for government employees to manage without outside monitoring? Should the organs from aborted fetuses be used for medical purposes? Does the media concentrate too much on scandals or other sensational events and miss the underlying issues that may be ultimately more important?

Icons with Ethical Problems

When photojournalism and ethics are combined as a topic for discussion, Time magazine's, "150 Years of Photojournalism" issue should be analyzed in a more critical manner. After consulting with experts in the field, the editors of the photojournalism issue reproduced in the introduction, "The Ten Greatest Images of Photojournalism."

"There are hundreds of unforgettable news pictures," the subhead explains. "Some record great events, others the small but resonant ones. In our view these ten-images of war and peace, love and hate, poverty and triumph-are the ones indelibly pressed upon the mind and heart" (" 150 years of photojournalism," 1989, p. 2).

Ironically, 8 of the 10 photographs have ethical problems associated with them or the photographer. Another "unforgettable news picture" is made more unforgettable through computer digital manipulation.

Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner moved a corpse to illustrate, in separate images, a Union and a Confederate soldier. Robert Capa and Joe Rosenthal were accused of stage managing their famous photographs. Dorothea Lange and Alfred Eisenstaedt were criticized by their subjects for not paying them for their famous poses. The pictures of Bob Jackson and Eddie Adams were considered too gruesome by many members of the general public. Gene Smith regularly posed his subjects and manipulated his prints with a variety of techniques that included double printing. And finally, in a demonstration of the manipulative potential of computer technology, a photograph of the solitary moonscape portrait of Edwin Aldrin by fellow astronaut Neil Armstrong is transformed at the end of the issue to an invasion of the moon by a platoon of moon-walkers.

There is no doubt that for older Americans, the 10 images are among the strongest and most visually memorable icons of the 20th century. A committee from Britain or France might not have seven American-related images. A group of younger students of photography might include photographs more recent than 1971. Another panel might not have five pictures that are war-related, a portrait of a destitute family, an international disaster, a political assassination and a mercury-deformed child.

In 1989, 150 years since the announcements of the daguerreotype and the calotype processes, Time Inc. published an anniversary issue on photojournalism sponsored by a single advertiser, Kodak. (Copyright © 1989 The Time Inc. Magazine Company. Reprinted with permission).

Perspective. A top-10 list is shaped by a judge's perspective. Ethical determinations are shaped by perspective as well. Past experiences, present concerns, and emotions are some of the factors that shape your response to a photograph. Your perspective, your 10 greatest images, will differ from another's. And when you see a picture on the front page of your local newspaper of a mother crying over the death of her son, you will either be moved or offended by the image because of your perspective.

Ethical arguments are usually unsatisfying. There is no clear winner or loser when perspective guides a determination. But there must be some way to defend your action to a reader who does not share your personal perspective.

Writers and photographers for newspapers follow the same ethical principle of truthfulness outlined in ethics codes. Journalists would view as unethical a reporter who fabricated quotations. Likewise, a photographer who uses darkroom tricks to make a false image would probably be fired. The principle of truthfulness is easily defended by both writers and photographers.

It Is Hard to Hide a Camera

Ethical worlds often collide, however, because of the fundamental techniques the two reporters use to gather information. During a controversial news event, when a father grieves visibly over the loss of a drowned child, a writer can stay behind the scenes with pen and paper hidden. Facts are gathered quietly and anonymously. A photographer is tied to a machine that must be out in the open and obvious to all who are present. A videographer during the 1967 riots in Newark, New Jersey said, "a newspaper guy can huddle in a doorway or get it over the phone. But we've got to be in it to get it" ("The riot beat," 1976, p. 78).

Long lenses or hidden camera techniques can be used, but the results are usually unsatisfactory. Focus, exposure, and composition problems are increased with the use of telephoto lenses or hiding a camera. Besides being on ethically shaky ground, the use of hidden cameras is illegal in Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, South Dakota, and Utah.

The photographer, unlike the hidden writer, can be the target of policemen, family members, and onlookers who vent their anger and grief on the one with the camera. No call to journalistic principles of truthfulness will convince a mob not to attack a photographer in such an emotionally charged situation.

Because photographers must be out in the open to take pictures, the photographer's ethical orientation must be more clearly defined than with writers who can report over the telephone. A photographer must have a clear reason why an image of a grieving parent is necessary.

Photojournalism as a Profession

Although photojournalism is filled with many dark moments, the history of the field is also rich with pride and professionalism. Cliff Edom (1976), one of the most well-respected photojournalism educators in the country, credited Frank Mott, dean of the Journalism School at the University of Missouri, with inventing the term, photojournalism. In 1942, Mott helped establish a separate academic sequence for photojournalism instruction. For the first time, photojournalism was considered "as important to the field of communication" as its word equivalent.

In 1946, Joseph Costa, staff photographer for the New York Daily News, was elected president of the first national organization for newspaper photographers, the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA). Editor & Publisher magazine at the time wrote that the aim of the new organization was "to combine all elements of the working photographic press in America to raise and maintain the high levels of photography necessary to the advancement of pictorial journalism." Shortly thereafter, the first issue of News Photographer, the official publication of the NPPA, was printed (Faber, 1977, p. 27).

Academic standing, professional membership, and literature unique to the organization are fundamental criteria for the definition of a professional group. Since the early days of the NPPA, members of the photojournalism profession have seen academic sequences begun at universities across the country. NPPA membership has grown from a handful at their first meeting in Atlantic City to more than 9,000. News Photographer magazine has grown in coverage and stature to become one of the leading trade publications in the business.

Another standard of professionalism is the amount of self-criticism that occurs within the organization for the betterment of its members. From the first issue of News Photographer, articles have been written, not simply to introduce technical advances, but to critically examine the ethical behavior of press photographers. From relations with the police to the coverage of tragic events, ethical issues get a fair hearing within the pages of News Photographer.

Reactions to controversial issues is a result of the underlying principles that guide a person. Many times photographers and the general public are on opposite sides of a philosophical wall. As part of the journalism community, photographers see their role as providing readers with a record of each day's events. The community at large is benefited. That mission often leads to the taking and printing of disturbing, graphically violent images. Such an underlying philosophy at work for journalists could be interpreted as a form of Utilitarianism. Many members of the general public, however, are disturbed by such images. Readers often complain that they either do not wish to see such gruesome photographs in their morning newspaper or are concerned that the pictures will contribute to the grief of the victim's family and friends. The underlying philosophy for those letter writers is most probably the Golden Rule. It is important to understand that the two conflicting philosophies have long been debated by philosophers without a satisfactory resolution. Emotional issues find little room for compromise. Again, a person's perspective guides a response to a controversial photograph.

The main concern of this textbook, the workbook, and the computer program is to help you learn your own ethical perspective. Such an insight will help you understand the various perspectives in use by photojournalists, their editors, their subjects, and their readers. As photojournalism heads into the next sesquicentennial, the ethical principles photographers rely on, as never before, will be challenged. It is vitally important, as you start your career, that you consider being an ethical photojournalist. The photojournalism profession demands nothing less.

Chapter 2

Photojournalism Assignments and Techniques

When asked to describe a photojournalist, most people would probably tell of a slightly disheveled, camera-weighted, young photographer who scurries to troubled areas anywhere in the world to produce images that capture people in crisis. Quite a romantic view. The reality is different.

Most photojournalists, according to a 1982 survey, work for a daily newspaper, are college-educated men, have families, own homes, are in their mid-30s, and make under $25,000 a year (Bethune, 1983).

Photojournalists should consider themselves to be on an equal status as word journalists. Photojournalists are reporters. But instead of pen, notebook, or tape recorders, these reporters use a camera and its accompanying selection of technical devices to record events for each day's printed record. As reporters, photojournalists must have a strong sense of the journalistic values that guide all reporters. Truthfulness, objectivity, and fairness are values that give the journalism profession credibility and respect. From getting the names spelled correctly in a group portrait to not misrepresenting yourself or a subject, truthfulness is a value that gives the public a reason to rely on the accuracy of the news they read and see in their newspaper. If you are economically, politically, or emotionally involved with a subject, your objectivity will be put into question. A photographer's credibility will suffer if free gifts from a subject are accepted or if political views or personal opinions cloud news judgments. To be fair, a journalist tries to show both sides of a controversial issue, prints stories and photographs proportionate to their importance, and if mistakes are made, prints immediate, clear, and easily found corrections.

A photojournalist, from experience and education, must know what is and what is not news. The media are often criticized for concentrating their efforts on negative, often tragic events in their community. Journalism professors Ted Glasser and Jim Ettema (1989) reviewed the most commonly held news values: "prominence, conflict, oddity, impact, proximity, and timeliness." In their article, Glasser and Ettema argued that a journalist should also use common sense, taught in journalism schools or through work experiences, to decide what is news. Unfortunately, tragic events usually fit into most news value categories (pp. 18-25, 75).

Successful picture taking is a combination of a strong news and visual sense. It is no easy proposition. As reporters, photographers use their sense of news judgment to determine if a subject is worth coverage and to present a fresh or unusual angle to an ordinary event. As visual recorders, photographers must use their sense of visual composition to eliminate distracting and unnecessary elements in the frame. As t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Original Title

- Original Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 The Merger of Photojournalism and Ethics

- Chapter 2 Photojournalism Assignments and Techniques

- Chapter 3 Finding a Philosophical Perspective

- Chapter 4 Victims of Violence

- Chapter 5 Rights to Privacy

- Chapter 6 Picture Manipulations

- Chapter 7 Other Issues of Concern

- Chapter 8 Juggling Journalism and Humanism

- Appendix A NPPA Code of Ethics

- Appendix B Toward a Philosophy of Research in Photojournalism Ethics

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index