![]()

PART I

Exploring the ‘Ideal Victim’

![]()

ONE

The ideal victim through other(s’) eyes

Alice Bosma, Eva Mulder and Antony Pemberton

Nils Christie’s legendary article on the ideal victim is firmly placed within the victimological canon. Christie drew our attention to the mechanisms underlying the extent to which we grant individuals victim status. As Daly (2014: 378) summarised: ‘A victim status is not fixed, but socially constructed, mobilized and malleable’.

However, what factors influence this construction? Christie (1986) assumed that the most important reasons for perceiving a victim as legitimate and blameless are the specific character traits of the victim and of the relation between victim and offender. Substantiation on the reasons for this had no place in his brief chapter, but has only occurred in subsequent research and theorising. The first aim of this chapter is to expand on these two arguments using more contemporary theories that are important in (experimental and critical) victimology, namely, the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) (Fiske et al, 2002) and the Moral Typecasting Theory (MTT) (Gray and Wegner, 2009). The SCM can expand our insights into Christie’s criteria of weakness, blamelessness and femaleness, while the MTT can shed more light on the big and bad offender and the (non-)relationship between offender and victim. These two theories provide more insight into the role of stereotypes in the perception of the victim and the dynamics of the relation between victim and offender.

They not only further Christie’s (1986: 18) argument that ‘being a victim is not a thing, an objective phenomenon’, but also, in combination with the second half of our chapter, emphasise the redundancy of absolute victim(isation) characteristics as a factor in societal or individual constructions of the victim status. Indeed, where the first half of our chapter provides retrospective theoretical support of Christie’s views, the second half adopts a more critical stance. Again, we confront Christie’s perspective with more recent bodies of (theoretical) literature that go beyond the specific character traits of the victim and the relation between victim and offender, this time by emphasising the role of the observers of the victim, both individually and collectively, in determining whether the victim is seen as legitimate and blameless. We do this, first, through an analysis of the ideal victim against the backdrop of the work on the justice motive (Lerner, 1980; Hafer and Bègue, 2005). The justice motive – observers’ need to believe in a just world – opens up the possibility to critically examine the extent to which the victim’s innocence in fact makes her more or less ideal. This is a good deal more complicated matter than Christie made it out to be. The second analysis relates to the ongoing work on framing, which, in its initial conception, pre-dates Christie’s ideal victim. However, the work in communication and social movement studies following the path-breaking work of Erving Goffman in 1973 has blossomed over the past 20 years. It suggests that the way in which the ideal victim is put to use in political and public discourse is an example of a more general phenomenon, which at once opens up the possibility for other ‘ideal victim’ stereotypes, while at the same time restricting the extent to which the use of such stereotypes can be overcome.

Stereotypes and moral typecasting

Stereotype Content Model

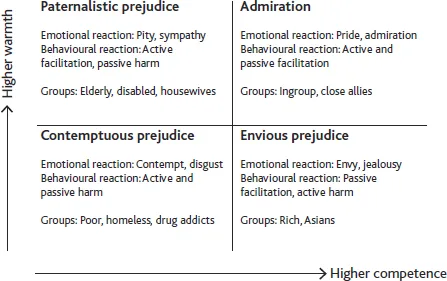

The SCM describes what emotions and behavioural tendencies people are expected to display towards a certain group, depending on the interaction between two broad continuous dimensions of stereotypicality that can be applied to any group. These two dimensions entail warmth on one of the axes, and competence on the other, and they are generally considered the two universal dimensions of social cognition (Fiske et al, 2007; for analogous concepts, see also Bakan, 1966; Spence and Helmreich, 1980). Groups and their members who are perceived as both warm and competent, which frequently means members of one’s own in-group, are hypothesised to trigger feelings of admiration, and to invite both passive and active helping behaviour from the perceiver. Groups who are perceived as neither warm nor competent (such as homeless people or drug addicts) generally elicit feelings of disgust or contempt, as well as both active and passive harming behaviour from the perceiver. Different combinations of the two dimensions may elicit either envious prejudice (high competence but low warmth) or, most relevant for the current chapter, paternalistic prejudice (low competence but high warmth). Paternalistic prejudice reflects the seemingly benevolent attitudes towards a non-dominant group that simultaneously functions to justify and facilitate differences in status and power in favour of the dominant group (Glick and Fiske, 2001).

Figure 1: Stereotype Content Model

Source: Adapted from Cuddy, Fiske and Glick (2008).

We expect that someone who has been victimised is generally perceived as non-threatening and easy to sympathise with, but is at the same time ascribed lower competence due to the fact that he or she ‘was unable to stand up for him- or herself’. The perception of high competence in addition to high warmth is a particularly incompatible combination for being an ideal victim because, as Christie (1986: 23) states, ‘sufficient strength to threaten others would not be a good base for creating the type of general and public sympathy that is associated with the status of being a victim’. This places the stereotypical and non-specified ‘ideal victim’ in the upper-left category of Figure 1, as the recipient of paternalistic prejudice. Behaviour that this group may expect from the social surroundings comprises active helping behaviour, but also neglect (Cuddy et al, 2008), depending on the convenience of either one action. Christie’s criterion that the ideal victim is generally weak in relation to the offender (ie scores relatively low on the dimension of competence) is reflected in findings which show that a person who has been victimised is particularly likely to be derogated on those character traits that relate to competence (Kay et al, 2005). It is perhaps also reflected in the notion that the groups that Cuddy et al place in the upper-left category are those thought to be the most vulnerable to victimisation. Although very few studies have so far incorporated both theories, the model helps to explain why members of certain groups, for example, businessmen or feminists (people who are perceived as highly agentic/competent but rather less warm or communal), would, in relation to most crimes, have a hard time being accepted as ideal victims. Christie mentions ‘the witch’ as a related example. Specifically, persons initially considered competent but not warm who are victimised, thereby losing much of their competent status, are particularly likely to find themselves shifting towards the contemptuous prejudice category, and hence to be met by contempt or disgust rather than sympathy. It goes against our intuition that someone competent becomes dominated or victimised, particularly by interpersonal (sexual) violence, and thus this type of person is unlikely to be considered as a wholly legitimate or blameless victim.

In turn, the concept of the ideal victim is helpful in explaining why it is so difficult for victims to get rid of their ‘victim status’ and stop being viewed with pity by the social surroundings. Considering the SCM, one might expect that an exertion of competence, for example, as shown by the emotion of anger or actions of rational profit making (as displayed by Natascha Kampusch after her escape; see Van Dijk, 2009), assists in redirecting the perception of the victim as placed in the paternalistic prejudice category towards the admiration (high warmth and high competence) category. However, this change in category would entail a change in label from ‘victim’ to ‘survivor’ because inherent to the definition of (ideal) victim is precisely a notion of weakness or vulnerability (Lamb, 1999).

Moral Typecasting Theory

The MTT (Gray and Wegner, 2009) taps into the relational aspect of moral situations and portrays ‘the idea that all moral perception is dyadic in nature’ (Arico, 2012). Moral situations, as we perceive them, are situations in which we can identify an act of wrongfulness or an act of goodness. The MTT states that a moral situation is rarely perceived as one in which a victim is wronged in the absence of a wrongdoer, or as one in which an offender does wrong in the absence of a victim. Rather, the act of wrongfulness or goodness creates the necessity to (albeit often unconsciously) identify two moral parties: one who acts, and one who is acted upon. According to the MTT, a moral patient cannot at the same time be a moral agent. The moral agent is the party capable of either helping or harming, while the moral patient is the one who experiences the deed. The MTT contributes to the notion of the ideal victim as someone who is essentially blameless. Indeed, Gray and Wegner (2011) found that the portrayal of someone as a victim, as compared to a ‘hero’, led to a decrease in assigned blame to that person. They conclude that the status of victim leads to a perception of moral patiency, and hence to a perceived inability to act or be held responsible for acts. In some moral situations, the distribution of roles is clear enough: ‘It is in everyone’s interest to protect our children against deviant monsters lurking in the streets and parks’ (Christie, 1986: 20). On the other hand, other situations speak to our moral senses but objectively lack offender and/or victim, asking of the observer a vast amount of effort to label each party (Gray et al, 2012). Christie (1986: 23) suitably describes that in Medieval times, sickness and misfortune were still unanimously accorded a moral status, meaning ‘People could bring it [sickness and misfortune] upon each other, with witches as intermediators’.

In cases of crime victimisation, it is simple to speak of a moral situation in which a wrongful act occurs. The offender, then, ought not only be perceived as big and bad, but also as the one who does a big and bad thing to the victim. Indeed, in reality, we see a strong correlation between these features of the actor and the act, and hence between the notion of the ideal offender and the MTT. In an ongoing study by Pemberton and colleagues, life stories are collected from (indirect) victims of severe crimes, including homicide and physical and sexual violence. In one of the interviews, a victim of attempted manslaughter by her mentally ill husband recalls a conversation with a police officer during which she is repeatedly told that ‘her husband is ill’. She shares her frustration about her own position and exclaims ‘yes, I know by now that he is ill, but then what am I?’. This telling example hints at how the less morally agentic a ‘big and bad’ offender becomes in the eyes of the beholder, in this case due to mental illness, the less a victim is perceived as a moral patient. An example on a larger scale is given by Christie when he talks about the second type of non-ideal victim, who is the ‘worker’. As it is practically complex and, moreover, largely undesirable for (governmental) institutions and the ruling classes to pinpoint themselves down as the agents, the situation of the ‘working class heroes’ remains morally unsaturated: ‘Workers become victims without offenders. Such victims are badly suited’ (Christie, 1986: 25).

The MTT finally serves as a valuable supplement to Christie’s criterion of the ideal victim as someone who has no relation with the offender. In fact, the MTT poses that a perceived relation between victim and offender is of the utmost importance, but that it needs to be an unequal and inversed relation between patient and agent. The unequal relationship entails that the agent needs to be perceived as more powerful than the patient/victim. If the agent is big and bad, then the victim needs to be weak and innocent, which is, indeed, the inverse relationship also touched upon by Christie. In his words, ‘Ideal victims need – and create – ideal offenders. The two are interdependent’ (Christie, 1986: 25). Allowing for a broad interpretation of the word, we suggest that a relation is created between victim and offender as soon as victimisation becomes a possibility. The existence of a relation between offender and victim need not problematise the status of ideal victim as long as it is a relation of opposites and opposition (or clear oppression), rather than of perceived compliance. This may serve to explain why (futile) resistance during sexual victimisation is found to be such a significant factor in the establishment of the blamelessness of the victim (Davies et al, 2008; Van der Bruggen and Grubb, 2014), although not a criterion expanded upon by Christie. Failed resistance shows that a victim was far from compliant in his or her victimisation, but still a moral patient who could not help being acted upon. No resistance endangers the desired simplicity of the moral dyad, whereas successful resistance does the same and virtually changes a moral situation into a non-issue.

To conclude, the SCM and MTT contribute to a more in-depth analysis and nuanced view of the ideal victim criteria that have been proposed by Christie. They also, respectively, provide more empirical evidence as to why the witch and the worker are two particularly informative examples of non-ideal victims.

The justice motive and framing

The justice motive

The previous theories emphasised and supported several of Christie’s key arguments. However, they also form a starting point for our main point of criticism, namely, that the criteria listed by Christie are neither necessary nor sufficient for someone to be granted the status of ideal victim.

When answering the question ‘Who is the ideal victim?’, one seems to be stuck in a catch-22. The approach that Christie takes is that the ideal victim is characterised by innocence. However, as we will see in this paragraph, the especially blameless and innocent might trigger observer reactions that include blame and derogation. We could also argue that the ideal victim is the victim who is treated as if (s)he is blameless and innocent, as a reward for being victimised (Rock, 2002). We are hence left with a chicken-or-egg question: is it the extent to which the victim is ideal that influences reactions to them, or do reactions to the victim establish to what extent they are ideal? In the following paragraphs, we will explore the (ideal) victim through others’ eyes and see that these eyes are necessary for the idea of the ideal victim.

First, the form of the ideal victim can change significantly depending on the situational context. Van Dijk (2009) points out that the ideal victim of restorative justice differs greatly from the ideal victim of retributive justice. Similarly, it has been pointed out that to be perceived as a legitimate/blameless (rape) victim in court, a victim needs to display certain qualities that are unspecified in Christie’s listed criteria, such as sincerity and a thoughtful demeanour. As suggested by Larcombe (2002: 145):

the point to emphasize is that the attributes of a ‘successful rape complainant’ are likely to be subtly but significantly different from the moral qualities of the chaste, middle-class, married woman at home – the figure normally identified as the ‘ideal’ rape victim.

Second, a victim may be accepted or rejected as legitimate not only on the basis of (context-dependent) victim characteristics, but also depending on the (implicit) needs or motives of the observer. An important motive that shapes people’s attitudes towards victims is the belief in a just world (Lerner, 1980). According to the theory of the belief in a just world, people inherently believe – or, better, are motivated to think and behave as if they believe (Pemberton, 2012) – that the world is a just place where people get what they deserve. Being confronted with a victim, of course, is not in accordance with the view that the world is a just place – especially when this victim is blameless and innocent. However, despite this type of counter-evidence, research has shown that people (implicitly) defend this world view – in which good people deserve good outcomes and bad people deserve bad outcomes – because it has a positive influence on their well-being (Hafer and Rubel, 2015).

Defending this world view can be done in different ways. Often, it happens in accordance with what one might intuitively expect and what Christie describes about the ideal victim: when an observer encounters a legitimate and blameless victim, meaning a good person or deserving victim, the observer will react in a way that leads to ‘granting the complete and legitimate status of being a victim’. More concretely, the observer will initiate positive actions towards the victim, such as compensating the victim or empathising with the victim. Additionally, the observer could predominantly focus on the bad nature of the offender. Believing that bad people deserve bad outcomes, the observer might punish the offender as a way to inflict this bad outcome upon the (big and) bad offender.

However, the same motive of believing that the world is a place in which good people deserve good things and bad people deserve bad things might lead to opposite reactions. In particular, when observers feel sceptical about their possibilities to ...