Introduction

In August 2009, South African athletics fans exulted when Caster Semenya won the women’s category 800m race at the World Athletics Championship in Berlin. But as TV cameras zoomed in on her hair beaded tightly to her head and her bulging biceps flexed in a sign of victory, viewers and officials of the International Association of Athletic Federations (IAAF) started wondering whether the sprinter was actually biologically female. This signalled the beginning of a long inquiry in which the IAAF would attempt to determine the runner’s sex. It also sparked a series of global debates in which discordant views about the configuration of Semenya’s genitals became proxies for tensions surrounding the intersections of gender, race, and Western epistemologies.

After the Australian daily The Sydney Morning Herald announced that Caster Semenya “is technically a hermaphrodite” (Magnay, 11 September 2009), the (then) leader of the ANC Youth League Julius Malema reacted strongly, asking:

Hermaphrodite? What is that? Someone must tell me what is hermaphrodite in Pedi? That woman is Pedi. What is hermaphrodite in Pedi? There is no such a thing [as] hermaphrodite in Pedi, so don’t impose your hermaphrodite concepts on us. You are either a woman or a man… And why should we—you know—accept the concepts that are imposed on us by the Imperialists?

(Cited in howzit MSN news, September 12, 2012)

These statements generated a flurry of reactions from a variety of social actors who accused Malema of reproducing the ideology of the gender binary, a set of beliefs that denies anything that does not fit in neatly with the male/female dyad. Critics also pointed out that Malema ignored the existence of a sePedi1 word, setabane, which encapsulates the co-existence of male and female biological characteristics and is mainly used derogatorily. Leaving aside for a moment Malema’s linguistic ignorance or strategic forgetfulness, it is important that his statement not be dismissed too quickly, for it contains an element of ‘Southern’ resistance against Northern institutions trying to label, define, and ultimately control African experiences.

Three years later, another South African athlete—Oscar Pistorius—gained considerable media attention when he was accused of murdering his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp. The Pistorius trial received extensive coverage by South African and international media, including a dedicated TV channel on the private broadcaster DSTV. Pistorius did acknowledge shooting at his partner, but claims that he did so unintentionally, as an act of defence against a perceived intruder. At the time of writing (October 2014), Pistorius has been found guilty of manslaughter and is awaiting sentencing.

Interestingly, we are told by his defence team that Pistorius, fearing for his life, “screamed like a woman.” This claim is used to counter neighbours’ testimony that they had heard Reeva’s cry for help in an altercation with her boyfriend that night. His pitch of voice notwithstanding, Pistorius said that “it filled me with horror and fear of an intruder or intruders being inside the toilet. I thought he or they must have entered through the unprotected window.” Granted, intruders can be of any gender; they can also be of any race, or age for that matter. In South Africa, however, the cultural image of the ‘burglar’ carries specific gendered and racial overtones that have roots in the apartheid past. In his testimony, Pistorius did employ the masculine pronoun “he” to refer to the alleged intruder, but he shied away from the overt usage of racial categories.

That being said, it is notable how some key South African analysts have interpreted his testimony. The title of an article by Sandile Memela in the British Guardian is a case in point: “If Oscar Pistorius Had Shot a Black Man, Would Anyone Care?” (Emphasis added.) Memela puts words to the nexus of masculinity and blackness, an intersection that in South Africa is often invisible because it is taken for granted. According to Memela,

The black man is always a suspect, a target. And for the rest of the world, it is understandable and acceptable if a white man shoots to kill to defend his land, property and family… As a white male you do not kill a white woman, especially the one you profess to love. Your role and responsibility is to protect and defend her against black men.

(Memela, April 30, 2014)

Also in The Guardian, South African writer Margie Orford wrote that “Pistorius has insisted that he thought it was an intruder, an armed and dangerous man intent on robbery, rape and murder.” Orford goes on to explain that the panic invoked by Pistorius is nothing other than “the old white fear of the swart gevaar (black peril),” a form of perceived threat which “[u]nder apartheid… was used to excuse any and all kinds of violence” on the part of white South Africans (Orford, March 4, 2014, emphasis in original).

The controversies surrounding Semenya and Pistorius are in my view the most vivid materializations of the three facets of masculinity that are highlighted in this book. To start with, they illustrate that masculinity is a relational concept, because it only makes sense vis-à-vis its binary counterpart: femininity. They also show that masculinity is never in the singular, but is instead a set of performances that one carries out by employing linguistic and other meaning-making resources within normative constraints about how a man should sound, appear, and behave. This multiplicity of masculine positions is due to the complex ways in which gender intersects with a variety of other categories such as race, social class, age, and national identity, to name just a few. Finally, Caster Semenya in particular reminds us that masculinities are not necessarily synonymous with biological maleness, but can be dislocated from it.

Performances

It is relatively uncontested in contemporary scholarship in the social sciences and humanities that one is not born but rather becomes a man (see de Beauvoir 1952). But how does one turn into a man? By developing into a man once and for all? Or is manhood a never-ending process of becoming? These questions can be answered with the help of Judith Butler (1998a), a queer/feminist thinker who in my view has explained most lucidly how sex, gender, and sexuality have become “entangled in knots that must be undone” (225–226).

Gender Is Performative

Butler argued famously that gender is performative. Following Austin’s (1962) canonical definition, a performative is an utterance that is less a description of pre-existing arrangements than a linguistic formula through which social reality is produced. A good example of “performativity’s social magic” (Butler 1998b) can be found in marriage ceremonies, in which the linguistic act of pronouncing “I do” turns the speaker from an unmarried person into a legally wedded husband or wife. What does it mean then that gender is performative? What kind of social magic is produced by gender?

When a doctor or midwife exclaims in an English-speaking context “It’s a boy,” Butler (1993) would argue, they are not simply describing the corporeality in front of their eyes: a crying and wriggling body with a small protuberance between the legs. That exclamation is an “interpellation” (Althusser 1971) that boxes that small body into the linguistic pigeonhole of the pronoun “he” and brings into being a set of rules and expectations about how that body should look, think, and behave. These norms will be consistently enforced by a variety of authorities and institutions such as school, church, family, and the military.

For Butler, gender is also performative because “[t]here is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its results” (1990: 25). Density of writing style aside, this quotation captures in theoretical terms a point that was made in the introductory section above, namely that masculinity is not a uniform, essential trait—in the singular—that certain individuals (and not others) have by virtue of specific biological endowments. Instead, masculinities are nothing but a series of performances—in the plural—that can be done with the help of a variety of meaning-making resources.

Does this mean that masculinities are like a wardrobe of clothes that can be chosen and changed on a whim? Butler would dispute such an interpretation, highlighting that “[g]ender is the repeated stylization of the body, a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame that congeal over time to produce the appearance of substance, of a natural sort of being” (Butler 1999 [1990]: 43–44, emphasis added). The “highly rigid regulatory frame” consists of those normative, context-specific beliefs about what counts as masculine (or not) that were evoked in the exclamation “It’s a boy!” These norms are not ingrained in people’s minds randomly or idiosyncratically, but are the results of particular social, cultural, and historical developments (see also Cameron 2014). They are like the calcified residue of long-standing percolations through which certain bodily shapes, poses, facial expressions, haircuts, clothing, activities, linguistic features, and styles of speech are repeatedly and consistently associated with men but not with women.

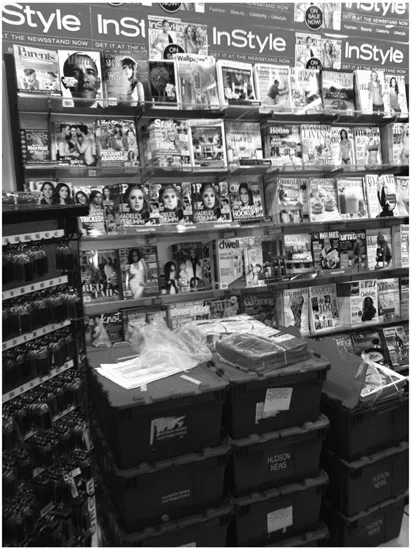

A rather mundane materialization of these indexical processes that link men with particular traits can be found in Plate 1.1, which represents a newsstand at Dulles Airport outside Washington, DC (see Milani 2014b for a more detailed analysis of gender and sexuality in “banal” (Billig 1995) public spaces). Like their female counterparts in Plate 1.2, the men on the cover pages of the lifestyle magazines in the picture are young and attractive, but they are larger, rugged, and muscular. These representations portray men and women as having opposite and complementary bodily configurations: men are muscled, strong, and display the need to protect, whereas women are beautiful, petite, and show the need for security (see Goffman (1977) for a ground-breaking analysis of the visual enactments of these gender stereotypes and Baker (Chapter 2, this volume) for quantitative evidence of this phenomenon in the United States). It is also worth noting in this context that Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, and Scientific American are placed directly under Men’s Journals, whereas Bon Appetit, Fine Gardening, and Furniture are situated near Women’s Health.

The front-page images and the spatial arrangements of the magazines are neither arbitrary nor ideologically innocuous. They “exaggerate gender difference and create the impression that gender distinction is integral to the functions, importance, and uses of human beings in social and familial systems” (Kitch 2009: 62). The problem here lies in the normative connections between men, ‘hard’ science, and technical abilities, on the one hand, and women and ‘soft’ skills such as everyday cooking, sewing, gardening, and interior design, on the other. These associations testify to more or less subtle sexist trends that, after decades of feminism, still seek to create power differentials between the two genders. Whereas women should be relegated to the world of creativity and the domain of the private, the public sphere and the practical ‘stuff’ should be left to men.

Plate 1.1 Gender arrangements—Men

Plate 1.2 Gender arrangements—Women

What is on display—quite literally—at the Dulles Airport newsstand are visual manifestations of the indexical processes that lead to the creation of particular cultural models or types of masculinity (and femininity) (see also Kiesling, 2011). These are recognizable cultural formations—scripts—that one needs to “cite”—as Butler (1993) would say—in order to fit in and qualify as a ‘normal’ man (or woman).

Hegemonic Masculinity: Representations and Practices

The masculine representations on the front covers of men’s lifestyle magazines are ideals, instances of what R. W. Connell (1995) calls “hegemonic masculinity”—the dominant and “currently most honored way of being a man [in a particular context]” (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005: 832). Hegemonic status is less the result of violence and raw force than of “discursive persuasion” (Messerschmidt 2012: 58), that is, the complex manufacturing of consent in which the media and other institutions play a key role (see Herman and Chomsky 1988).

In its original definition, hegemonic masculinity entails the subjugation of women and the vilification of gay men (Connell 1995: 77–78). It is “not normal in the statistical sense; only a minority of men might enact it” (Con-nell and Messerschmidt 2005: 832). Yet it has become the norm, requiring “all other men to position themselves in relation to it” because of the highly valued “ideals, fantasies, and de...