![]()

Embedding the World Trade Organization

Headquartered in Geneva, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has become one of the most high-profile international organizations in existence today, equipped with not just a broad array of legislative agreements but also its own quasi-court system able to give those rules teeth. It is a landmark achievement in the history of not only global economic governance but also inter-governmental negotiations. The continually expanding notion of what is ‘trade’ has seen its jurisdiction expand considerably with huge social significance at all levels. Nothing else like it exists. Appropriately enough, the WTO has attracted substantial attention – both critical and supportive – from national politicians, the media, various publics and academia. With only a few years away from the organization's twentieth anniversary, in 2015, the field of WTO studies has grown exponentially.

There is significant disagreement over how to understand the WTO in both academia and wider public debates. For some, the WTO is an apolitical legalistic means to escape or at least lessen the impact of old school state-to-state trade politics. For others, however, the WTO is an imperialistic project led by realpolitik concerns that sweep unheedingly over the needs of individual societies. Both poles of this debate suffer, as this book argues, from a basic fallacy: that is, they treat the WTO as abstract from the historical or social environment in which it operates. This is because at each end of this spectrum, the WTO institution is rarefied as alien to the very social interactions through which it is made possible and continues to change. Too little attention is given to how the WTO is itself imbued with power relations linking multiple political identities within the production of contemporary global trade governance. The task undertaken here is to analyse the WTO as embedded within a particular context, constituted via a series of specific social relations and practices. The analysis works to unpick those constitutive social practices, looking under the bonnet, and the primary tool utilized in this endeavour is a discourse theoretical methodology developed from the work of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe (2001).

The WTO cannot be limited to a formal political structure or any fixed set of actors, but consists of a much more complex and diffuse process. A discursive approach is shown to advance social science on the WTO by incorporating both ideational and material explanations. Demonstrated in the book, the salience and value of this perspective can be evidenced within new empirical research into the formation, operation and transformation of the WTO in which the category of agency and its political arena – including its governance domain – is subject to change. Such an approach is critical within WTO studies, where otherwise key categories like ‘Member states’ and the institution of the WTO are taken as given facts without examining their discursive character. The task of the book is then to unpick this institution and show its discursive character within a series of social practices stretching far beyond any institutional walls. In particular, interviews and observation with civil society activists demonstrate how new political identities continue to emerge as part of the political arena in which the WTO is constituted.

This book can be read as both a critical intervention within WTO studies, but also as part of the family of new approaches to international (or global) political economy (IPE) and international organizations studies that re-embed the technocratic architecture of global governance within particular social contexts (e.g. Watson 2005; Gammon 2008; Hobson and Seabrooke 2007; Antoniades 2010). In so doing, the point is better to understand how that architecture comes to exist, be maintained and is subject to change. Wider literature along this vein has focused on new actors and changed concepts of the political arena.

The first section of this introductory chapter reviews current studies on the WTO. Within this literature, there is contestation over two key questions: how to define their object of study; and how they map agency. Second, the chapter outlines the problem of defining agency in the WTO with specific reference to the discursive construction of the ‘Member states’ identity that more mainstream approaches in WTO studies have taken to be a clear designator of actorness but that covers over the important question of who or what is able to act in the WTO. In this light, the third section makes the argument that the WTO is a sedimented discursive formation – a series of social practices linked within an historically contingent relational sequence that exceeds any fixed or finite borders. As will be explained further on, social practices are all those practices through which individuals interact – either directly or indirectly – with one another. This situates the approach within the growing body of IPE literature that seeks to highlight the social processes constituting global economic transactions (Watson 2005; Gammon 2008; de Goede 2005; Antoniades 2010). In this respect, and with particular reference to the work of Matthew Watson, a discursive approach to the WTO contributes to Karl Polanyi's project to exhibit the social embeddedness of the market, but here, with focus on the technocratic institutional basis of that market (Watson 2005: 141–58). The fifth and final section summarizes the book's research strategy by outlining how the WTO comes to appear within its approach. It shows that treating the WTO as a sedimented discursive formation allows research better to understand the organic character of its central object of study and the interplay between both order and uncertainty that exceeds its legal-institutional borders and provides the conditions for an ongoing process of change.

The book makes apparent that the approach advocated in this chapter, and developed throughout the proceeding empirical chapters, reinvigorates WTO studies by repositioning the organization at the centre of a dynamic discursive context. It is in this context that the concept of ‘trade’ and its governance, as well as who or what constitutes an ‘actor’ within its political arena, is subject to a continual process of change whether the relationship between the constitutive social practices is rearticulated. The reader is presented with a provocative intervention that challenges existing studies on both the politics and the institutional identity of the WTO. As such, the book develops an analytical approach equipped to appreciate how both the material and ideational factors overlap so as to make the WTO possible, and explain change within the governance of global trade.

The WTO as the ‘rule of law’ or as ‘power politics’

The literature on the WTO has grown to fill a decently sized library and yet can be summarized as falling somewhere between viewing the WTO as either the rule of law or the product of power politics. Variance is found along a spectrum based on the extent to which institutional rules/norms may be argued to ameliorate capability (e.g. economic, military) differentials outside the institution. Consequently, some studies consider the legal-institutional design paramount – the ideational (e.g. Jackson 2009, 2000; Hoekman and Kostecki 2009; Matsushita et al. 2003). Others stress the weakness of formal norms of decision making against the strength of realpolitik considerations – the material (e.g. Kwa 2003).

The field of WTO studies is dominated by research on the WTO institution itself, the series of legal texts it hosts, and the possibility that it represents the beginnings of a world polity. First, much literature exists to provide a general overview of the formal institution understood as the ‘WTO’ (Hoekman and Kostecki 2001, 2009; Jackson 1998a, 1998b, 2000; Matsushita et al. 2003; Adamantopoulos 1997). Second, there is more specialist focus upon the trade agreements held under its banner, such as the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) (Sauvé and Stern 2000). Third, research has focused extensively on both the use of legal mechanisms, with particular attention on the Dispute Settlement Body (Bronckers 2000; Cameron and Campbell 1998), but also the role of the WTO as a constitution at the centre of a global trade polity (Cass 2005). Fourth, the ideational literature includes publications debating future reform of the institutional arrangement (Jones 2010; Barfield 2001; van der Borght et al. 2003).

Research that concentrates on the role of material forces driving the WTO has emphasized the highly politicized character of global trade governance (Lanoszka 2009; Wilkinson 2006; Kim 2010). This includes work on WTO negotiating practice and decision making (Steinberg 2002; Schott and Watal 2000; Hoda 2001); disparities in the influence exercised by different Member states in the WTO (Dunkley 2000; Kwa 2003); the relatively weak position of developing countries in the WTO (Narlikar 2001; Blackhurst et al. 1999; Meléndez-Ortiz and Shaffer 2010); human rights impact of WTO rules (Joseph 2011); the role of non-state actors (e.g. ‘non-governmental organizations’) (Wilkinson 2005; Scholte 2004); and the implementation of WTO agreements (Blackhurst 1998).

Whilst neither literature is mutually exclusive – nor, indeed, are scholars permanently wedded to either one or the other of the ideational and materialist camps – there is a gap in understanding between how material and ideational explanatory factors interact to make the WTO possible. The relevance of this gap becomes clearer when considering the problem of defining agency in the WTO.

The problem of defining agency in the WTO

The puzzle of two WTOs – one ideational and the other material – is illustrated in the difficulty of defining who or what constitutes an actor in the WTO. The emergence of actors as subjects able to alter their political environment forms a key question for discourse theory, as will be shown when discussing the book's research strategy. However, for now it helps first to outline exactly why there is uncertainty over how to define agency in the WTO.

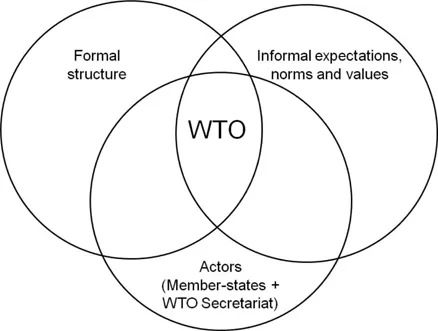

Formally, there are at least two categories of ‘actor’ utilized in the literature. First, there are the ‘Member states’.1 These are nation-states that have applied and been accepted as Members of the WTO. Second, WTO negotiations and the monitoring of domestic trade policy within Member states are facilitated by a Secretariat with a staff of approximately 550, and a headquarters office in Geneva (WTO Secretariat 2008: 2). Incorporating the formal structure, the informal practices and the two categories of actor as modelled in the literature, the WTO appears as in Figure 1.1.

The use of a Venn diagram is not meant to represent the actual political operation of the WTO but the intersection of variables taken into account within how the WTO is defined as a research object.

The first category of actor includes the professional trade diplomats representing their national governments (or the European Union, in the case of EU member countries), as well as trade ministers and civil servants. Several studies have focused on the composition of these delegations (e.g. Blackhurst et al. 1999: 20), which vary greatly depending on how a Member prioritizes specific negotiations, as well as the resources determining their capability to provide technically qualified personnel to attend negotiations.

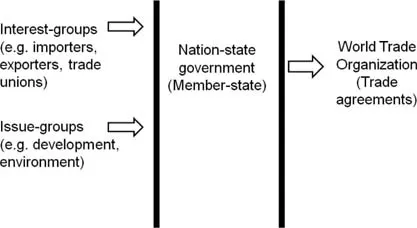

The two-stage flow model by which much of the literature understands how ‘business interests’ and ‘non-governmental organizations’ are to influence the formation of WTO agreements further evidences the significance of how one defines a Member. This is argued by one of the most influential texts within the field of WTO studies (Hoekman and Kostecki 2009), and takes the form

Figure 1.1 The WTO as modelled in the literature

of a pluralist model in which the national level consists of competing ‘interests’ spread across different identities such as ‘businesses’, ‘trade unions’, ‘issue-groups’ (e.g. environmental), and so on. Within this model, it should be noted that ‘business’ does not constitute a unified position because sub-identities such as ‘exporters’ or ‘importers’ will presumably possess diametrically opposed ‘interest-positions’. Additionally, ‘trade unions’ includes representatives of workers in both import/export industries and might therefore be expected to be similarly heterogeneous.

The contestation between these ‘interests’ is understood to occur at the national level, so that the negotiating position of that country's trade delegation to the WTO is the product of that contestation. Business, trade unions and non-governmental actors have no formal direct access to the WTO and so this is seen to imply that Member states effectively act as the gatekeepers to the WTO through their ownership of the franchise over decision making (Hoekman and Kostecki 2009: 159–61).

The WTO is thus understood as the product of nation-states balancing domestic ‘interests’, and can be simply modelled as in Figure 1.2.

The model can be multiplied to reflect the number of Member states, with the WTO at the centre and each Member acting as gatekeeper against its own plurality of competing domestic ‘interests’. The perspective taken by Hoekman and Kostecki positions the various ‘actors’ in their respective fields of

Figure 1.2 Member states as the gatekeepers to the WTO

influence, so that, for example, ‘businesses’, ‘trade unions’ and ‘environmentalists’ operate as ‘lobbyists’ at the ‘national’ level. However, despite stating that non-state actors are not able to ‘lobby’ the WTO directly, Hoekman and Kostecki do briefly note the role played by, in particular, financial corporations such as American Express and Citibank in the Uruguay Round which provided the negotiations, and thus the initial sedimentation, of the series of practices that would become the formal institutional structure and trade agreements that emerged as the ‘WTO’ in 1995 (Hoekman and Kostecki 2009: 159). They note that large businesses have been important in providing the ‘force’ by which various trade agreements have been first created as wellas then implemented (ibid.:159).

The literature traces the rise in political support for ‘open markets’ with the emergence of new industries such as consumer electronics and aviation, which have the most to gain from reduced trade restrictions, according to such accounts (Dunkley 2000: 23). Understood thus, the history of multilateral trade negotiations might be traced as a product of a balance between competing ‘interests’, where the present is indicative of the ascendency of such global businesses as Citibank.

In this respect, Hoekman and Kostecki (2009: 62) suggest that the WTO is a ‘network’, with the WTO Secretariat at the centre. The WTO includes ‘official representatives of members based in Geneva, civil servants based in capitals, and national business and nongovernmental groups that seek to have their governments push for their interests at the multilateral level’ (Hoekman and Kostecki 2001: 53). This suggests a model in which the ‘WTO’ exists, then, as the sedimentation of the practices of a multiplicity of ‘actors’.

However, the anatomy of politics at play in the WTO becomes increasingly complex if one acknowledges the transnationalization (or ‘globalization’) of ‘businesses’ and ‘non-governmental organizations’, so that the flow of influence or force exceeds the ‘nation-state’ as gatekeeper to the WTO, and moves to the supranational level so as to be able to affect multiple nation-states and thus play one off against the other (Hoogvelt 2001). Though the Member remains as gatekeeper to the WTO, Hoekman and Kostecki's multi-level model of WTO policy formation appears increasingly untenable as the nation-state is shown to be not a distinct and isolated identity, as such, but part of a network of ‘influence’ that exceeds (and supersedes) national boundaries. Hoekman and Kostecki (2001: 1...