![]()

Rethinking the Location of Translation in Contemporary Theatre

Cristina Marinetti

What is incredibly fascinating about theatre, and has been its driving force from very early on, is its immediacy and transience, that characteristic of being there one moment and gone the next. And this is particularly poignant in street and improvised performance, because of the lack of the architectural frame which makes us aware of the ‘fiction’ of the theatre. This quintessential aspect of theatre is encapsulated in the moment when a street actor says a word, or strikes a pose and catches the attention of a passerby. And how do they do that? How do they make you stop? Because they are doing or saying something different, something out of the ordinary, something worth stopping for and watching. In that moment we have ‘theatre’, a moment of extraordinary exchange that creates the distinction between actor and spectator. The actors, as a creative force, use their body in space to build a unique connection with the spectator which is consumed in the moment of performance.

Eugenio Barba describes this use of the actor's body as ‘extra-daily’ techniques, and he sees them as what defines at its core the notion of performance. For Barba the way we use our bodies in daily life is substantially different from the way we use them in performance. We are not conscious of our daily techniques: “of how we move, we sit, we stand, we carry things, we kiss” (Barba and Savarese 9). In performance the body's daily techniques “are replaced by extra-daily techniques, that is, techniques that do not respect the habitual conditionings of the body” (ibid.). And it is this stage ‘presence’, created by the body of the actor in performance, that defines the theatre in the same way that it has defined attempts to study translation in the theatre.

RESISTING TRANSLATION: PRESENCE, DRAMA, AND PERFORMANCE

But it is also this very ‘presence’ which makes theatre resistant to translation. The immediacy of the theatrical experience, predicated on the here and now of the performance, destabilizes the assumption of stable meanings of the dramatic text. Writing about “the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction”, Walter Benjamin sees photography and its technique of infinite reproduction as the motive for a reconceptualization of the work of art:

Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. This unique existence of the work of art determines the history to which it was subject throughout the time of its existence … [T]he technique of reproduction detaches the reproduced object from the domain of tradition. By making many reproductions, it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence. (220–21)

Concepts of originality and authenticity are predicated for Benjamin on the notion of “presence in time and space”, and mechanical reproduction, by detaching the work of art from tradition, “substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence”. So it is ‘presence’ in time and space, like the actor on stage at the moment of performance, that creates a sense of authenticity, the experience of witnessing an act of creation. This brings us to the paradox of translation in the theatre: how can one reproduce in another language and context ‘theatrical performance’, which is by definition unique and unrepeatable?

Pioneering scholars in theatre translation have been fascinated by this paradox and have offered great insights to our understanding of the nature of the dramatic text and its consequences on the theory and practice of translation. Drawing on contemporary Italian work on theatre semiotics, Susan Bassnett was the first to seek ways to uncover the actor's ‘presence’ in the text. The dramatic text was seen as a ‘blueprint for performance’ which the translator was to recognize in the source text, decode and recode in the target text. In an analysis of three translations of Racine's Phèdre she unveils how two of the translators succeed in reproducing the rhythm of the French verse thereby also recoding in the target language the patterns of physical gesture of the actor, and she concludes:

In short, the translation process has involved not only a sequence of linguistic transfers from SL to TL on the level of discourse signification, but also a transfer of the function of the linguistic utterance in relation to the other component signs of the theatre discourse. (2002: 124)

In later writing, Bassnett gradually moves away from the structural idea of ‘gestic subtext’ and recognizes the limits of it as a concept which was born of a specific approach to a specific type of text, namely a structural approach to ‘the theatre of psychological realism’ (1998). But the idea of ‘presence’, so embedded in the notion of performance, continued to be productive for thinking about theatre translation.

For Patrice Pavis, the physical presence of the actor—their gestures, movements, tone of voice, and facial expression—becomes one with the written word of the text. This presence, which he terms the ‘languagebody’, should substitute equivalence as a constituent unit (and criterion) for translation, since the main object of theatre translation is not the equivalence of texts but the appropriation of the source text by the target culture (137–38). Broadening the discussion to the processes of rehearsal and staging, Sirkku Aaltonen tells us that not only actors but “playwrights, translators, stage directors, dress and set designers, sound and light technicians as well as actors all contribute to the creation of theatre texts when they move into them and make them their own” (32), leaving their mark on the theatre text, which signifies only to the extent that it has been inhabited.

My difficulty with Aaltonen's and Pavis's models lies in the fact that they both see as unproblematic a view of translation where interpretation occurs in discrete phases. Both Aaltonen's metaphor of time-sharing—different agents inhabiting the text at different moments—and Pavis's different phases of the articulation of the language-body suggest a separation of the ‘linguistic’ from the ‘dramaturgical’ and the ‘performative’. The risk of such perspectives is that the creative potential of cultural encounters begins and ends with the translated text, which is then passed on to dramaturges, playwrights, directors, and actors who no longer have the means to engage with the language of the source culture.

BRITISH THEATRE: ‘NOT LOST IN TRANSLATION’

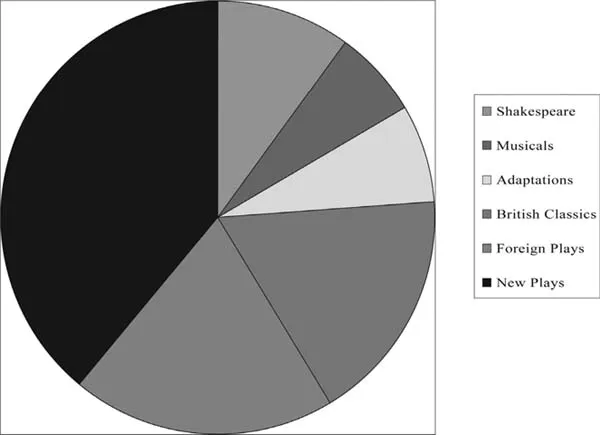

The British case is particularly poignant, both because of its geopolitical importance as the gateway between Europe and the world, and because it presents an extreme case of marginalization of foreign drama and, as we will see, of the figure of the translator themself. As Jack Bradley recently put it, “the British scene is not lost in translation” (Baines, Marinetti, and Perteghella 187). As Figure 1.1 illustrates, the percentage of translations commissioned and produced by British theatres is minimal compared to other European countries, even in the most established and publicly funded theatres. The National Theatre, for example, between 1995 and 2006 produced 250 plays, and of those 250 only forty-one are translations (16.4%):1

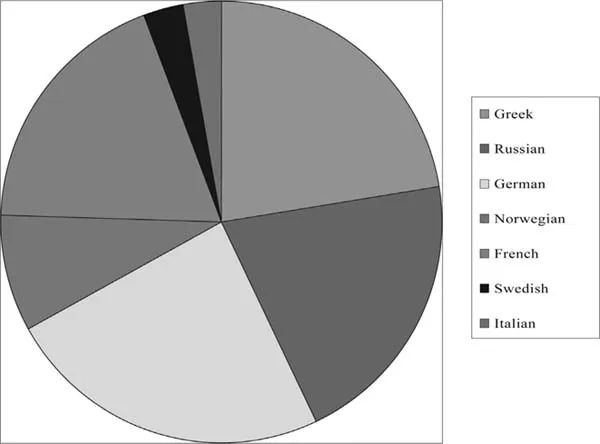

If we look at the plays that fall under the category of foreign titles (Figure 1.2), it becomes even more interesting. While Greek, Russian, German, Norwegian, and French plays appear at first sight to be well represented, different productions of Oresteia and Oedipus count for over 70% of the Greek plays, the Russian titles are mostly Chekhov, the German Brecht and the Norwegian Ibsen, the French contribution is made up entirely by Marivaux and Molière, while the Swedish and Italian correspond to Strindberg and Eduardo respectively. So not only do mainstream British theatres

Figure 1.1 Type of plays produced by the National Theatre between 1995 and 2006.

not invest in translations, but when they do they do not go for new or lesser known authors, they retranslate the classics.

And here is where the situation becomes difficult for the translator, because most theatres in these cases commission the translation work not to a bilingual translator but to a monolingual playwright. In many cases bilingual translators are employed only initially to provide what is called ‘a literal translation’ that is then passed on to a monolingual playwright who ‘makes it performable’. There is nothing wrong with this method of working in principle, except for the idea that there is such a thing as ‘a literal translation’ and that you can neatly separate the language of the play from the performance context within which it was developed. But as a working practice it is very positive in that it allows one to combine linguistic and cultural expertise with an ability to write for actors and deliver a product that will be functional to a performance. Unfortunately, however, this collaboration is often, in practice, damaged by the imbalances of power between the translator and the writer. Unlike in many other countries in Europe, the literal translator in the UK is considered a technician at best. They do not need to be experts on the particular author nor on the theatrical tradition the play originates in. Moreover, they are usually not included in the process of rehearsal and staging, they do not receive a percentage of the royalties, nor do they have ownership of their own translation which becomes the property of the company.2

Figure 1.2 Language distribution of the foreign plays.

In a recent interview, award-winning writer and translator Christopher Hampton talks about an example of this collaboration, and although it sounds like an extremely successful collaboration, one cannot help but feel a little uncomfortable at his description of the literal translator:

Yes, no Uncle Vania was first. And Ashley Page directed it and he got a literal translation. Actually I had studied French and German so I was technically a linguist but I had only done one year of Russian and I didn't even take the O-level at school, so I sort of knew the alphabet and so on but very little else. So Ashley Page got this woman called Nina Fraud who was the editor of the Russian cookbook and lived somewhere in North London and she did a literal translation and I asked her to make it as literal as possible, to observe as closely as possible the punctuation and the length of the sentences, which she sort of did, and we did it an act at a time over several months. I would do it as it were one act at a time and we would go and spend an evening at Nina's and she would cook some fabulous meal and we would go through it pretty much line by line, because the intention was, and my intention always is when I translate, to try and get as close to the original as possible and to try and reproduce it in its effects as closely as possible, so that's what we did over several months and then we went into rehearsal with Paul Scofield, Michael Lamarsh. We pretty well did what the Royal Court does, which is not a word was changed. (qtd. in Baines, Marinetti, and Perteghella 56)

If we look at Hampton's words from the perspective of the text, of the product of translation, it seems that the collaboration was successful and produced a translation that was both performable and informed of the linguistic and cultural context of the original, but if we read it as a document of the role of translators in the theatre, we can argue that their position seems to have gone back to that of the enthusiastic amateur of the eighteenth century. There is no sense of the need for academic or professional input. She was the expert in the Russian language and he was the expert in writing plays, writing for actors and making the text suitable and successful for a British audience. But, as anyone who has studied theatre or who has ever translated will know, it takes years of reading and studying the work of an author in the original to be able to unlock the patterns of a play. Who had the expertise to access Chekhov's language and poetics? To understand the connotations of the language of his characters in the socio-historical context in which they were created? And more importantly, why was that knowledge not just of the source language but of its cultural and theatrical connotations not considered relevant for the translation task? But there is something else that we can glean from Hampton's words, and which is at the basis of the widespread use of monolingual playwrights as translators in British theatres, that the very notion of theatre translation in British cultural discourse has shifted, moving radically away from something that has to do primarily with language.

It seems that a focus on performability, on the ‘presence’ of performance in the dramatic text, has lead to a marginalization of drama translation in practice, which is however accompanied by a rhetoric of fidelity and authenticity in public discourse: “We pretty well did what the Royal Court does, which is not a word was changed”. So is translation becoming obsolete in the theatre? If we define translation as the interlingual transfer of dramatic text then the answer seems to be yes, at least in Britain.

TRANSLATION AS CULTURE: TRANSNATIONAL, MULTILINGUAL, AND POST-DRAMATIC THEATRE

Recent scholarship in translation studies, however, has moved away from a definition of translation as the movement of linguistic and cultural signs from a source to a target text and, influenced by the translation turn in cultural studies, the focus has shifted to the translational nature of culture. In this view, translation becomes less a procedure to which cultures can be subjected than itself the very fabric of culture:

Today the movement of people around the globe can be seen to mirror the very process of translation itself, for translation is not just the transfer of texts from one language into another, it...