- 298 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Originally published in 1971.

Long regarded as a classic, this volume is one of the most systematic treatments of Hwa Yen to have appeared in the English language. With excellently translated selections of Hwa Yen readings, factual information and discussion, it is highly recommended to readers whose interests in Buddhism incline toward the metaphysical and phenomenological.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Buddhist Teaching of Totality by Garma C C Chang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Realm of Totality

The Infinity of Buddha's Realm

What does a Buddha1 see and hear? How does He act and think? What does He know and experience? In brief, what does it feel like to be a Buddha? These questions have been asked by all Buddhists throughout the ages, just as Jews, Christians, Moslems, and Hindus have always asked about their gods and prophets. If these questions are answerable at all, the answers must be very difficult. To raise a question is to reveal a state of mind, and to answer a question is to try to share one's experience with others. An answer cannot make sense if it is given to those who do not share the experience it implies. Let me illustrate this.

A caravan was slowly making its way through a Tibetan desert under a scorching sun. Among the travelers was an American who, under the pressure of extreme heat and thirst, exclaimed, "Oh, what wouldn't I give to have a big glass of ice-cream soda right now!" A Tibetan nearby heard this remark, and asked the American, "What is this 'ice-cream soda' you want so much?"

"Ice-cream soda is a wonderfully delicious, cold drink!"

"Does it taste like our butter-tea when it is cold?"

"No, it is not like that."

"Does it taste like cold milk?"

"No, not exactly—an ice-cream soda tastes quite different from plain, cold milk; it can have a great variety of flavors. Also, it bubbles up."

"Then, if it bubbles, does it taste like our barley-beer?"

"No, of course not!"

"What is it made of?"

"It is made of milk, cream, eggs, sugar, flavors, ice and soda-water. . . ."

The puzzled Tibetan still could not understand how such grotesque mixture could be a good drink.

Thus, communication becomes extremely difficult without a common ground of shared experience. Einstein's world is quite different from that of the average man. If the distances that separate people's worlds are too great, nothing can help to bring them together. When Buddha tried to describe His Experience to His audience, He foresaw this difficulty. In many of His discourses, as witnessed in the Sūtras,2 He often accompanied His expressions with an air of resignation, implying that Buddhahood is not something to be described in words or apprehended through thought. The basic difficulty lies in the fact that we do not share the same experience as the Buddha.

To reveal the unrevealable, and to describe the indescribable realm of Buddhahood, the Hwa Yen Sūtra,3 one of the greatest scriptures in Mahāyāna Buddhism, has presented us with an awe-inspiring panorama of Buddhahood for those aspirants who, despite all the inherent difficulties, are eager to have a glimpse of this great mystery.

The mystery of Buddhahood can perhaps be summed up in two words: Totality and Non-Obstruction. The former implies the all-embracing and all-aware aspects of Buddhahood; the latter, the total freedom from all clingings and bindings. Ontologically speaking, it is because of Totality that Non-Obstruction can be reached, but causally speaking, it is through a realization of Non-Obstruction—the complete annihilation of all mental and spiritual impediments and "blocks"—that the realm of Totality and Non-Obstruction is reached. In the pages to follow, we shall examine the philosophical, experiential, and instrumental implications of Totality and Non-Obstruction; but first let us read a few passages from the Hwa Yen Sūtra in order to get a far-reaching view of the Dharmadhātu 4—the infinity and totality of Buddhahood.

. . . Buddha replied to the Bodhisattva Cittarāja:5 "In order to make the world apprehend the numbers and quantities in Buddha's experience, my good son, you have now asked me [a question about the inconceivable, unimaginable, unutterable infinity]. Listen attentively, and I shall now explain it to you.

"Ten million is a koṭi; one koṭi koṭi is an ayuta; one ayuta ayuta is a niyuta; one niyuta niyuta is a binbara [a number followed by seventy-five zeros]; and one binbara is . . . [thus it goes on in geometrical progression one hundred twenty-four times more, and the number then is called] one Indescribable-Indescribable Turning. . . ."6

Then Buddha continued in the following stanzas:7

The Indescribable-Indescribable

Turning permeates what cannot be described . . .

It would take eternity to count

Turning permeates what cannot be described . . .

It would take eternity to count

All the Buddha's universes.

In each dust-mote of these worlds

Are countless worlds and Buddhas . . .

From the tip of each hair of Buddha's body

Are revealed the indescribable Pure Lands . . .

Indescribable are their wonders and names,

Indescribable are their glories and beauties,

Indescribable are the various Dharmas now being preached,

Indescribable are the manners in which they

ripen sentient beings . . .

Their unobstructed Minds are indescribable,

Their transformations are indescribable,

The manners with which they observe, purify and educate

Sentient beings are indescribable . . .

The teachings they preach are indescribable.

In each of these Teachings are contained

Infinite, indescribable variations;

Each of them ripens sentient beings in indescribable

manners.

Indescribable are their languages, miracles,

revelations, and kalpas . . .

An excellent mathematician could not enumerate them,

But a Bodhisattva can clearly explain them all . . .

In each dust-mote of these worlds

Are countless worlds and Buddhas . . .

From the tip of each hair of Buddha's body

Are revealed the indescribable Pure Lands . . .

Indescribable are their wonders and names,

Indescribable are their glories and beauties,

Indescribable are the various Dharmas now being preached,

Indescribable are the manners in which they

ripen sentient beings . . .

Their unobstructed Minds are indescribable,

Their transformations are indescribable,

The manners with which they observe, purify and educate

Sentient beings are indescribable . . .

The teachings they preach are indescribable.

In each of these Teachings are contained

Infinite, indescribable variations;

Each of them ripens sentient beings in indescribable

manners.

Indescribable are their languages, miracles,

revelations, and kalpas . . .

An excellent mathematician could not enumerate them,

But a Bodhisattva can clearly explain them all . . .

The indescribable infinite Lands

All assemble in a hair's tip [of Buddha],

Neither crowded nor pressing

Nor does this hair even slightly expand . . .

In the hair all lands remain as usual

Without altering forms or displacement . . .

Oh, unutterable are the manners they enter the hair . . .

Unutterable is the vastness of the Realm . . .

Unutterable is the purity of Buddha's body,

Unutterable is the purity of Buddha's knowledge.

Unutterable is the experience of eliminating all doubts,

Unutterable is the feeling of realizing the Truth.

Unutterable is the deep Samādhi,

Unutterable is it to know all!

All assemble in a hair's tip [of Buddha],

Neither crowded nor pressing

Nor does this hair even slightly expand . . .

In the hair all lands remain as usual

Without altering forms or displacement . . .

Oh, unutterable are the manners they enter the hair . . .

Unutterable is the vastness of the Realm . . .

Unutterable is the purity of Buddha's body,

Unutterable is the purity of Buddha's knowledge.

Unutterable is the experience of eliminating all doubts,

Unutterable is the feeling of realizing the Truth.

Unutterable is the deep Samādhi,

Unutterable is it to know all!

Unutterable is it to know all sentient beings' dispositions,

Unutterable to know their karmas and propensities,

Unutterable to know all their minds,

Unutterable to know all their languages.

Unutterable to know their karmas and propensities,

Unutterable to know all their minds,

Unutterable to know all their languages.

Unutterable is the great compassion of the Bodhisattvas,

Who, in unutterable ways, benefit all living beings.

Unutterable are their infinite acts,

Unutterable their vast vows,

Unutterable their skills, powers, and means . . .

Who, in unutterable ways, benefit all living beings.

Unutterable are their infinite acts,

Unutterable their vast vows,

Unutterable their skills, powers, and means . . .

Inconceivable are Bodhisattvas' thoughts, their

vows and understanding!

Unfathomable is their grasp of all times and all Dharmas.

Their longtime spiritual practice is incomprehensible,

So is their abrupt Enlightenment in one moment.

vows and understanding!

Unfathomable is their grasp of all times and all Dharmas.

Their longtime spiritual practice is incomprehensible,

So is their abrupt Enlightenment in one moment.

Inconceivable is the freedom of all Buddhas,

Their miracles, revelations and compassion

Toward all men!

Their miracles, revelations and compassion

Toward all men!

To explain the infinite aeons is still possible

But to praise the Bodhisattva's infinite merits

Is impossible . . . .

But to praise the Bodhisattva's infinite merits

Is impossible . . . .

Thereupon, Bodhisattva Cittarāja addressed the assembly thus:8

"Listen, O sons of Buddha, one kalpa (or aeon) in this Saha world—the Land of Buddha śākyamani—is one day and one night in the great Happy Land of Buddha Amita; one kalpa in the Land of Buddha Amita, is one day and one night in the Land of the Buddha Diamond Strength, and one kalpa in the Land of the Buddha Diamond Strength, is one day and one night in. . . . continuing in this manner, passing millions of incalculable worlds, the last world [of this series] is reached. One kalpa there, is again one day and one night in the Land of the Buddha Supreme Lotus; wherein, the Bodhisattva Samantabhadra and all the great Bodhisattvas now assembled here, are also present there, crowding the sky. . . .

". . . . When a Bodhisattva obtains the ten wisdoms, he can then perform the ten universal enterings. What are they? They are: To bring all the universes into one hair, and one hair into all the universes; to bring all sentient beings' bodies into one body, and one body into all sentient beings' bodies; to bring inconceivable kalpas into one moment, and one moment into inconceivable kalpas; to bring all Buddhas' Dharmas into one Dharma, and one Dharma into all Buddhas' Dharmas; to bring an inconceivable number of places into one place, and one place into an inconceivable number of places; to bring an inconceivable number of organs into one organ, and one organ into an inconceivable number of organs; to bring all organs into one non-organ, and one non-organ into all organs . . . to make all thoughts into one thought, and one thought into all thoughts; to make all voices and languages into one voice and language, and one voice and language into all voices and languages; to make all the three times 9 into one time, and one time into all the three times . . .

". . . Sons of Buddha, what is this supreme Samādhi that a Bodhisattva possesses?10 When a Bodhisattva engages in this Samādhi, he obtains the ten non-attachments . . . the non-attachment to all lands, directions, aeons, groups, dharmas, vows, Samādhis, Buddhas, and stages. . . .

"Sons of Buddha, how does a Bodhisattva enter this Samādhi, and emerge from it? A Bodhisattva enters Samādhi in his inner body, and emerges from it in his outer body . . . he enters Samādhi in a human body and emerges from it in a dragon body . . . enters Samādhi in a deva's body, and emerges from it in a Brahma's body . . . enters in one body, and emerges in one thousand, . . . one million, one billion bodies . . . enters in one thousand, one million, one billion . . . bodies, and emerges in one body . . . enters in a sullied, sentient being's body, and emerges in one thousand, one million . . . purified bodies; enters in one thousand, one million . . . purified bodies, and emerges in one sullied body; enters in the eyes, and emerges in the ears, in the noses, in the tongues . . . in the minds . . . enters in an atom, and emerges in infinite universes; enters in his self-body, and emerges in a Buddha's body; enters in one moment, and emerges in billions of aeons; enters in billions of aeons, and emerges in one moment . . . enters in the present, and emerges in the past . . . enters in the future, and emerges in the present; enters in the past, and emerges in the future . . . The Bodhisattva who dwells in this Samadhi can perceive infinite, immeasurable, inconceivable, incalculable, unutterable, and unutterably unutterable . . . numbers of Samādhis; each and every one of which has infinitely vast varieties of experiences—their enterings and arisings, remainings and forms, revelations and acts, natures and developments, purifications and cures . . . he sees them all, transparently clear. . . . A Bodhisattva who dwells in this supreme Samādhi,11 sees infinite lands, beholds infinite Buddhas, delivers infinite sentient beings, realizes infinite Dharmas, accomplishes infinite actions, perfects infinite understandings, enters infinite Dhyānas, demonstrates infinite miracles, gains infinite wisdoms, remains in infinite moments and times. . . ."

Obviously, the above quotations are too short, too discursive and unsystematic to describe the Totality of Buddhahood as depicted in the Hwa Yen Sūtra—a voluminous scripture of more than half a million words. Nevertheless, through these quotations, we can secure a small foothold from which to analyze and study the Realm of totality and Buddhahood.

In Buddha's reply to the Bodhisattva Cittarāja we are told of the vastness of a realm which, if translated in terms of numbers, would go far beyond the remotest edge of the empirical world. The passage leaves us with an impression that the author was speaking in the language of modern astronomy. The name given to the last number, the Indescribable-Indescribable Turning, is extremly interesting and significant. It is apparently not an arbitrary name given to denote a definite and inflexible number, but a descriptive term designed to portray the experiential insight of a vast mind. What does the Indescribable-Indescribable Turning mean? Why should an emotive word like indescribable be used here at all to define a number or quantity?

Exceedingly large or small numbers, including infinity at the two extremes, can easily be conceptualized and expressed in terms of symbols and abstractions, but they are difficult to experience or "touch" in an intimate and direct way. We have no difficulty in understanding the idea of a million, a billion, a trillion, or even of infinity, but it is very difficult for us to grasp or project these larger numbers in terms of empirical events. The world of symbols and abstractions is characteristically different from that of sense experience and insight. The former is, to use the Buddhist terminology, a realm of indirect measurement, and the latter, a realm of direct realization.12 It is said that in a Buddha's mind these two realms are not separate. The Yogācāra philosophers even go so far as to say that a Buddha's mind has only one realm, that of direct realization. A Buddha never "thinks," but always "sees." This is to say that no thinking or reasoning process ever takes place in a Buddha's Mind; he is always in the realm of direct realization, a realm that is intrinsically symbol-less. The claim that a symbol-less Buddha-Mind can convey its experience to men by means of symbols, is perhaps an eternal mystery that can never be solved by reason. But is it not also true that if such a mystery exists, it cannot be otherwise than indescribable—a term denoting the impossibility of approximating something through symbolization?

The pen of Leo Tolstoy can reproduce a living panorama of the battle of Borodino in our minds, but whose pen can reproduce the battles of Borodino, of Normandy, of Stalingrad, of Verdun, of Zama, of Okinawa . . . the one thousand and one battles, all at the same time? Is it not quite understandable, then, that Buddha had to resort to the use of this apologetic term, Indescribable-Indescribable Turning, to release the "tension" of conveying His direct experience of "seeing" the awesome panorama of Totality through such a pitiful means of communication as human language?

The Indescribable-Indescribable

Turning permeates what cannot be described . . .

It would take infinity to count

All the Buddha's universes.

In each dust-mote of these worlds

Are countless worlds and Buddhas . . .

From the tip of each hair of Buddha's body

Are revealed pure...

Turning permeates what cannot be described . . .

It would take infinity to count

All the Buddha's universes.

In each dust-mote of these worlds

Are countless worlds and Buddhas . . .

From the tip of each hair of Buddha's body

Are revealed pure...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

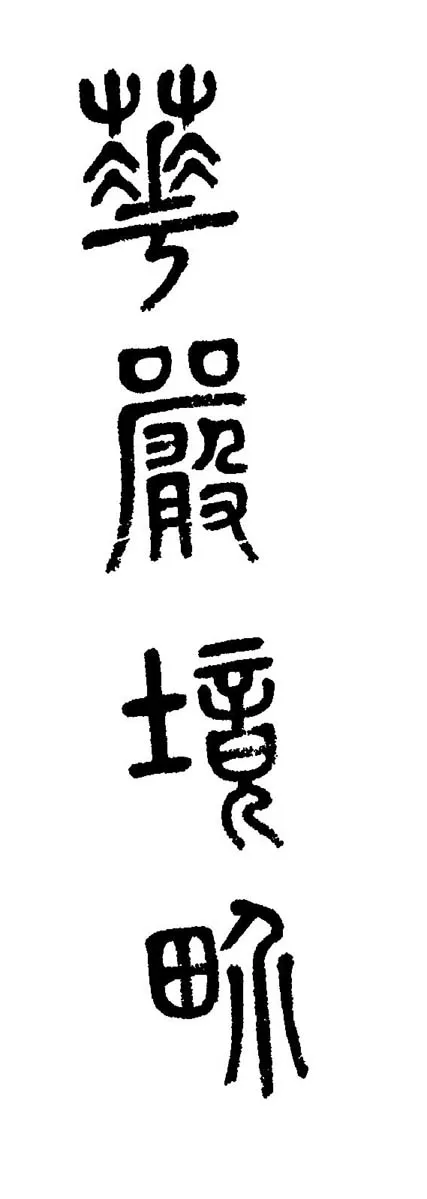

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Prologue

- One The Realm of Totality

- Two The Philosophical Foundations of Hwa Yen Buddhism

- Three A Selection of Hwa Yen Readings and the Biographies of the Patriarchs

- Epilogue

- List of Chinese Terms

- Glossary

- Index