eBook - ePub

Life in Post-Communist Eastern Europe after EU Membership

Happy Ever After?

- 237 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Life in Post-Communist Eastern Europe after EU Membership

Happy Ever After?

About this book

This book examines how membership of the European Union has affected life in the ten former communist countries of Eastern Europe that are now members of the European Union. For each country, political, economic and social changes are described and discussed, together with people's perceptions of the effects of EU membership. Overall, the book shows how the benefits of EU membership have differed between different countries, and how perceptions about the benefits also differ and have changed over time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Life in Post-Communist Eastern Europe after EU Membership by Donnacha O Beachain,Vera Sheridan,Sabina Stan,Donnacha Ó Beacháin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Poland

Introduction

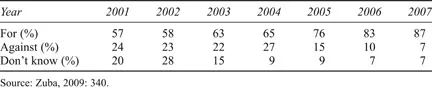

The year 2010 saw the sixth anniversary of Poland joining the European Union. Pointing to rising living standards, extensive investment in infrastructure and economic growth that spilled into the regions and rural areas, viewed from the perspective of the main Polish political parties, EU membership was a great success. This was echoed in the opinion polls with the number of supporters for Poland’s membership of the European Union amounting to 87 per cent in 2007. Optimism has been bolstered by increasing GDP since 2004 and the fact that among European economies, and those of Central and Eastern Europe in particular, Poland was least scathed by the crisis of 2008. The structure of this chapter is that the first section gives an overview of the political dimensions of the post-accession period and discusses the impacts of EU accession. The following two sections critically assess the economic and social impacts of membership of the European Union since 2004.

Political developments

To understand the impact of EU accession on politics this section begins with a brief outline of the political scene in Poland.

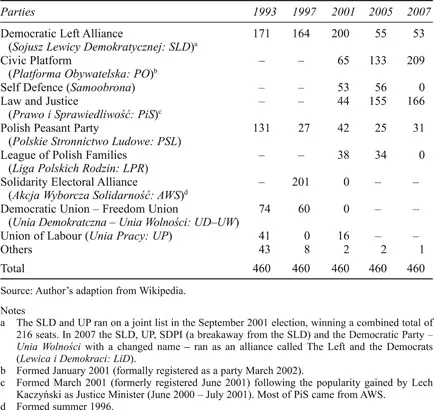

There has been deep-seated disillusionment and discontent with political parties. This is reflected in the fluidity of the post-1989 Polish political scene, characterised by extraordinarily high levels of electoral volatility and party instability (Table 1.1). This has led to regularly voting out of the standing government, with participating parties vanishing from the scene to reappear shortly afterwards in another form with a new name. Between 1990 and 2000, the main formal division in Polish politics was between politicians who had their roots in the Solidarity movement and those who had been in the ruling Communist Party.1 With other groupings they formed an electoral bloc called the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), which by the 2001 elections had become a political party – the SLD.

The September 2001 parliamentary election represented a watershed in Polish politics and major reshuffling of the party system. Four new parties got over 40 per cent of the vote between them and it saw the consolidation of the Civic Platform (PO) and Law and Justice (PiS). However, the biggest story of this election was that the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) – the communist successor party – won the election hot on the heels of Kwaśniewski’s re-election as president. This was the year that Poland was accepted for EU membership and it was negotiated and achieved under the auspices of the former communist party and president, who was a former minister of the communist regime.

Table 1.1 Polish election results (number of seats)

After 2001 the Civic Platform and the Law and Justice parties emerged from the Solidarity camp as new forces in Polish politics and went on to win the elections of 2005 (Law and Justice) and 2007 (Civic Platform). Civic Platform voters were clearly the most liberal in terms of their attitudes towards socio-economic issues (privatisation, tax, agricultural subsidies and welfare benefits), while the views of Law and Justice voters were generally more socially oriented. In general the Law and Justice Party appealed to the losers of transformation, particularly older people, while the Civic Platform tended to appeal to the winners of transformation and younger people. This was reflected in the voting patterns of migrants in the 2007 election with the established Polish community in the USA voting for Law and Justice, while 62 per cent of migrants in Europe/United Kingdom, who tend to be much younger, voted for the Civic Platform.

With a sharp polarisation of attitudes the parliamentary election campaign of 2001 opened the period of the most dramatic political debate about Poland’s membership in the European Union. Szczerbiak (2004) provides a good analysis of the stance taken by various political parties. He suggests that the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) and Civic Platform were Euro-enthusiasts who modelled themselves on the ideology and style of modern West European political parties; in the case of the SLD on social democratic parties, while the Civic Platform followed the pattern of liberal or Christian democratic parties.

The League of Polish Families (LPR) and Self Defence were firm Eurosceptics. The LPR was formed on the basis of a nationalist model. Self Defence was formed as a native populist party not directly comparable to any elsewhere in Europe (ibid.). Strong criticism of the European Union was one of its main platforms and it appealed to the rural electorate, focusing on threats to the Polish farmer. Both parties politicised their perceived tensions between the Polish national tradition and culture and the new European cosmopolitan culture.

Law and Justice (PiS) and the Polish Peasant Party (PSL) could be described as Eurorealists and were a combination of both the nationalist tradition (PiS) and the native tradition (PSL) as well as aligning themselves with West European models. The Polish Peasant Party had an ambivalent attitude to European integration. In the 2001 it was in favour of tough membership negotiations, demanding full subsidies for farmers and an 18-year prohibition on foreigners’ purchase of agricultural land (ibid.). The Law and Justice Party were ambivalent from the beginning. They were caught between Poland’s historical anchoring in the structures of Western Europe and therefore supported accession, but had reservations and after accession attacked the European Constitution resolutions, wanting references to the ‘Christian roots of Europe’ in the preamble.

With regard to public opinion in the June 2003 referendum there was a large vote, of 77 per cent in favour of joining the European Union, with a turnout of around 59 per cent. This settled the primary question of whether or not Poland should be in the European Union and Eurosceptics (LPR and SD) and the Eurorealists (PSL and PiS) moved in the direction of pro-European positions. However, after the elections in 2005 when PiS gained power they avoided openly criticising Europe and focused on negotiating the attitude of its own government and pointing to economic and cultural risks (lack of identity) saying that ‘it would stoutly defend Polish interests’. The PiS negotiations about the treaty reforming the European Union, which ended with the Polish government’s refusal to sign the Charter of Fundamental Rights and the adjournment of voting rules in the Council of the European Union until 2007, were presented as their greatest victory.

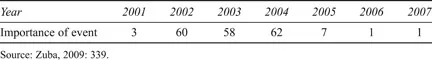

By 2005, the absence of European issues in political debate in parliamentary elections was striking. After the elections of 2001, Europe had been one of the key issues, while after the elections of 2005 it became a minor one with little discussion by the main parties. This could be attributed to the fact that EU membership had been achieved and, therefore, the debate shifted from whether Poland should join the European Union to debates about the shape and future of the European Union and the role of Poland. This was reflected in public opinion. Table 1.2 shows that after 2005 the European Union was regarded as an issue by a negligible number of people. Parallel to this, the level of support for the European Union in Polish society had risen to 87 per cent by 2007 as Table 1.3 shows.

Table 1.2 Percentage of respondents selecting the European issue as the most important event of the last year, 2001–2007

Table 1.3 Level of support and opposition to European Union in Polish society, 2001–2007

However, this was not reflected in enthusiasm for European elections and the turnout of the electorate in Poland in 2009 was 24.5 per cent with only Lithuania (21 per cent) and Slovakia (20 per cent) registering lower (NSD, 2009). The EU election reflected the national picture with twenty-five Euro MPs elected from PO, three from PSL and seven from the SLD–UP.

The implementation of EU structural funds in Poland appeared to be a driving force of Europeanisation by creating an unprecedented opportunity for catching up with Western Europe and building a regional development policy. However, difficulties in the absorption and implementation of these funds revealed problems regarding governance, building local democracy and enhancing civil society.

The new territorial system came into effect in 1999 in order to conform with EU NUTS2 regions; this reduced the number of regions for 49 to 16 with elected councils. However, central government still retains a high degree of control over regions because it designates its representatives in the region – the voivodes – whose role is to safeguard state interests. Further, the decentralisation of functions has not been followed by the decentralisation of financial competences. The vagueness of European Commission recommendations has allowed the safeguarding of central government’s trusteeship and according to Dabrowski (2007) ‘an apparent empowerment of regions hides de facto a recentralisation of power with the government controlling the purse strings’.

Governance is not aided by the complexity of the system, with one hundred institutions in charge of the implementation, intermediation and management of structural funds. Continuities of the previous regime in terms of excessive bureaucracy have caused significant delays. Further, there have not been adequate adjustments to the legal framework concerning public–private partnerships and invitations to tender. A lack of cooperation, particularly marked at local authority level, has meant continuations of political culture where clientelism dominates and the privileging of local interests persist (Dabrowski, 2007).

A key intention of the disbursement and implementation of the structural funds was to devolve governance and encourage the building of civil society and civic participation. A main element of partnerships within the current system of the distribution of structural funds are the Regional Steering Committee composed of representatives of regional and local authorities, social partners, business associations, universities and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). In practice, however, it is argued that non-state partners do not have a significant impact on debates or choice of projects. Rather the debate is dominated by the representatives of local authorities who consider the Regional Steering Committees as a tool for lobbying in favour of their projects. Concerning the cooperation of regional actors, Europeanisation has had ambiguous consequences. It has, on the one hand, generated a proliferation of partnerships and the mobilisation of regional actors, but allowed some to seize the opportunity offered by the imprecision of European prescriptions to favour their own interests and privilege the participation actors from the private sector at the expense of representatives from civil society.

Before 2004, assessments of the state of the Polish trade union movement suggested that its role was declining and peripheral. The main trade unions are NSZZ Solidarnosc (Niezależny Samorządny Związek Zawodowy ‘Solidarność’) and OPZZ (Ogolnopolskie Porozumnie Związków Zawodowych: All-Poland Alliance of Trade Unions). OPZZ was the government-sponsored union which was set up in 1984 as a counterweight to Solidarnosc. In recent years it has started operating as a ‘proper’ trade union. Forum Związków Zawodowych is a new trade union federation founded in 2002. There are smaller union organisations, including the Solidarity ‘80, a splinter group which looks back to the union traditions of the early 1980s. Solidarity has approximately 722,000 members (5 per cent of the work-force), OPZZ 600,000 (4 per cent) and FZZ (2 per cent). About 600,000 are in other uni...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Foreword by Aleksander Kwaśniewski

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Poland

- 2 The Czech Republic

- 3 Slovakia

- 4 Hungary

- 5 Slovenia

- 6 Lithuania

- 7 Latvia

- 8 Estonia

- 9 Romania

- 10 Bulgaria

- Conclusion

- Index