One way to get a sense of the real dynamics that characterize communication on the Internet is to spend a little time listening in on it. Listening in on Internet ‘chatter’ is something that this book will have a lot to say about but for now let me just quickly sketch a scenario for you. Ben Hedrington has created a Google App Engine project called ‘spy’ (available at spy.appspot.com) which allows a user to input a search term, say ‘Nike’, and then watch as the engine scrapes every use of that term, pretty much real time, from a number of the most popular social networking sites around the world. So, the results are a continuously streaming set of reports from users of Twitter, FriendFeed, and anyone who produces or comments on content with an RSS feed (which would include virtually all blogs on the net) who happens to be talking about Nike while you are sitting there at your computer. The talk that you can see is, naturally, international. Some of it clearly emanates from one aspect or another of Nike’s corporate communication effort and some it is produced by retail outlets with RSS feeds from their websites but much of it represents informal chat between friends, colleagues, and acquaintances. Listening in on these short snippets of Nike-focused chat, one hears people complaining about their Nike + equipment not working properly, others stating how much they use the same equipment and how it has kept them running through the winter, while others remind each other of the Nike sponsored run in their area on the weekend, some compare other products to Nike’s while others use Nike as a metaphor for a variety of characteristics. Hedrington’s ‘spy’ application gives us an instant window onto the current state of Nike’s brand identity and value—it can show us how, right now, a brand fits into the normal social life and rhetorical framework of people who live a significant portion of their life online. It would appear to be an excellent way to monitor and gauge the ‘buzz’ around a product, brand, or idea. Imagine that you were a marketing consultant working for Nike—surely such an application would provide you with a perfect way of constructing instantaneous communication audits for your client and then measuring the effectiveness of any marcom efforts you implement? You are literally eavesdropping on your stakeholders …

Hedrington’s ‘spy’ is a good example of one of the ways in which the technological underpinnings of the Internet (in this case, RSS feeds and APIs for web sites like Twitter) are being used to gather the substance of “informal” conversations around the globe and present them for considered consumption by whoever is interested. This process is known as data or text mining and it is a vital part of the way in which organizations are trying to leverage the astounding urge to communicate that consumers display on the Internet. And the name that Hedrington has chosen for his application is demonstrative of the attitude toward the building of communication relationships with consumers that such processes are built upon. ‘Spy’, and all such data mining applications, can provide realtime feedback on the results of marketing communication but it is not the feedback of conversation or dialog. Rather, data mining is typified by a stance of ‘listening in’, of trying to ‘overhear’ what is being said about you (as brand). In learning what others might be saying about you behind your back (or when they think you are not listening) you may be able to use this information to alter your message or your presentation when you do address them face-to-face. Could we call this process interactive, though? Or, perhaps we might ask, who might call this process interactive and why?

In this opening chapter, I will be examining exactly how the terms “interactivity”, “conversation”, and “dialog” have been constructed and used within the academic and practical environments of marketing communication. In order to approach these issues effectively, though, we must first examine the way in which the concept of communication itself has been ‘positioned’ within the discipline of marketing. The way that marketing thinks of “interactivity” and uses the metaphors of conversation and dialog are inextricably linked to the understanding held by the founding and mainstream voices of marketing theory of what it means to communicate and how communication is carried out.

THE TRADITIONAL MODEL

Some of the reasons for this uneasy situation can be apprehended through an examination of one of marketing’s most canonical texts, Philip Kotler’s Marketing Management. First published in 1967 and now in its 12th edition (co-written with Kevin Lane Keller), Kotler’s tome is the standard by which all other undergraduate and MBA marketing textbooks are judged. Marketing communication issues are afforded their own section (one of eight), under the rubric Communicating Value, comprising three chapters wherein the authors endeavor to introduce, contextualize, and strategize all of the elements of the Integrated Marketing Communication mix. As a natural overture to this enterprise, Kotler and Keller overview the concept of communication from a marketing perspective—in their rather instrumentalist terms, “how communications work and what marketing communications can do for a company” (Kotler & Keller, 2006, p. 536). The first thing that even a cursory engagement with the text makes clear is that there is no attempt made to define what communication might be outside of the marketing environment. The authors squarely treat communication as a component of marketing rather than choosing to situate marketing communication as a part of a larger field of communication. Instantly, therefore, marketing communication is isolated. It is purposefully cut off from the issues, theories, and discourses current in both the academic realm of communication studies and the more practitioner-focused areas of journalism and media production. Instead, Kotler and Keller construct a definition of marketing communication which is breathtaking in its presumption and (as I will show) so completely characteristic of the Kotlerite mainstream discourse of control:

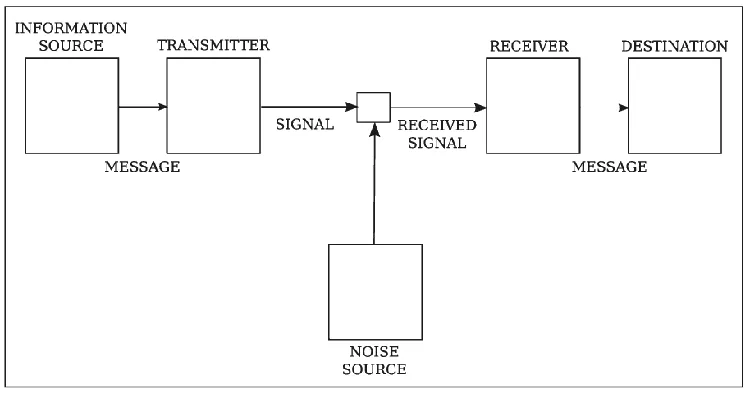

Considered closely, the implications of this position are that communication within a marketing environment is something done by marketing to consumers; there is one “voice” and it is the voice of the brand and it is used to “establish” a dialog. Clearly, then, there can be no dialog that is not instigated by the brand and concomitantly there can be no relationship that is not initiated by the brand. The assumption here is that the consumer is passive, solely reacting to the initiative of the marketer. Perhaps it might be argued that one small sentence should not be held as representative of an entire authorial position. Yet, the assumptions that inform Kotler and Keller’s definition of marketing communication are made even more manifest in their ensuing discussion of the two communication models they advance as the providers of “the fundamental elements of effective communications” (ibid., p. 539). The macromodel presented by the authors is an expanded version of the classic Sender–Message–Receiver model advanced by Claude Shannon (1948; see Figure 1.1) and then re-presented with an introduction by Warren Weaver in the 1949 study, The Mathematical Theory of Communication.

This model, variously referred to as the transmission model, the SMR model, or the injection or hypodermic model, although highly influential upon the communication theory of the 60s and early 70s now suffers from widespread dissatisfaction and mistrust in mainstream communication and media studies fields. In marketing, however, the opposite is the case and Shannon and Weaver’s model has been adopted and maintained as the dominant communication paradigm, although those marketing academics and practitioners who have actually worked their way through the reasoning of the original mathematical treatise could probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. As an illustration of the distinct dichotomy between the two fields on this matter, an examination of McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory, an undergraduate textbook written by Denis McQuail, first published in 1983 and now in its fourth edition, sees the SMR model presented as a historical artifact of a “largely unchallenged North American

hegemony over both the social sciences and the mass media” (McQuail, 2000, p. 46) that saw the mathematically-based transmission model of communication as able to “answer questions about the influence of mass media and about their effectiveness in persuasion and attitude change” (ibid., p. 47). McQuail quotes E. M. Rogers’s judgment that the SMR model led the study of communication into an “intellectual cul-de-sac” that concentrated almost exclusively on mass communication effects while noting that “traces of functional thinking and of the linear causal model are ubiquitous” (ibid.) in communication research to this day. The tremendous power of the SMR, functionalist approach is readily acknowledged by McQuail and the other mainstream communication academics whose work his textbook is designed to summarize. As such, Kotler’s presentation of the SMR model topographically appears to be identical to that found in current overviews of communication studies, in that it is the model that appears always at the start of a presentation on the theory of communication. Yet, what for most contemporary communication scholars is something to be historically contextualized and deconstructed, the starting point of the story, as it were, is for Kotler the fountainhead, the source. So, for example, McQuail continues his study by noting that the “rejection by researchers of this notion of powerful direct effect is almost as old as the idea itself” (p. 48) and goes on to outline the way in which the obvious failings of the model have even been used to help excuse its adoption by a western “liberal-pluralist society” which needs to downplay the possibilities of “subversion by a few powerful or wealthy manipulators” (ibid.). Alternative models and paradigms, based upon critical work produced by the Frankfurt School, are then presented and this leads onto a broad discussion of ideologies informing the communications field. Readers are specifically told that “they are not obliged to make a choice between” (ibid., p. 52) the dominant and alternative paradigms; McQuail suggests instead that these discourses of ideology and paradigm are involved in a continuing, polyphonic dialog. In Kotler’s presentation there is no room for such considerations: A declarative reliance on the existential copula, coupled with that old advertising saw, repeated injunctions, means that alternatives cannot be countenanced:

The contrast between the two approaches is clear: Communication studies is wrestling with its instrumentalist, functionalist legacy while mainstream marketing continues to hold the transmission paradigm as central to its core theory.

An understanding of communication which unproblematically conceives of a unified ‘sender’ and a unified ‘target audience’, deliberate (and sanctioned) ‘encoding’ and ‘decoding’ and speaks of ‘monitoring responses’ is an understanding of communication founded upon a deep allegiance to a control systems paradigm. Kotler, after all, sees marketing as a management process and it should come as no surprise that he would view communication as a management process as well. Kotlerian marketing ‘senders’ seek to control the message and therefore the ‘receivers’ through a careful, informed management of message creation, presentation, and consumption. The more carefully the communication is managed then the more successful it will be: success, of course, being the achievement of specific marketing goals. Consequently, communication takes its place alongside the marketing channel, the product-line and logistics as simply another element that needs to be minutely controlled in the service of the organization.

Researchers from a communications studies background might feel themselves entitled, then, to look upon marketing communications as a field permanently stuck in embarrassing adolescence, fixated upon a model of communication that everyone else has grown out of. Indeed, there are even marginal voices within marketing academia that have been presenting alternative ways of approaching the communication process for almost 20 years. Communication theorists and marginal marketing mavens have taken the lessons of predominantly literary-based theories such as reader response, poststructuralism, deconstruction, and new historicism and applied them toward a rebalancing of marketing and marketing communication in favor of multivalent interpretations, active audiences, and a general problematizing of many of the management assumptions at the heart of mainstream marketing. Many of these (comparatively) radical voices point to the apparently more enlightened, grown-up discourses that constitute the communication and media studies disciplines as models of where marketing theory and research should be heading (Shankar, 1999; Robson & Rowe, 1997).

Yet, this wondrously evolved elder spirit of communication studies is itself very much a rhetorical construction, a strategic fiction designed to inculcate embarrassment in the country bumpkins of mainstream marketing communication. Pick up any issue of the Journal of Communication, Human Communication Research, or Communication Theory (to flagrantly single out the august organs of my own professional organization, the International Communication Association) and one will be greeted with predominantly instrumentalist research papers that assume discernible effects and are predicated upon essentially transmission models of communication. There are definite streams of postmodern critical voices in these journals but so there have been in quite traditional marketing and advertising publications for a considerable time. Perhaps more importantly, much of the postmodern thought in evidence in both communication and marketing theory remains tied to (often more subtly expressed) paradigms of transmission and control.

The influence of Claude Shannon’s paper “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” in 1948 and Warren Weaver’s subsequent introductory framing of it a year later in the book-length expansion have had a foundational effect upon both mainstream and marginal communication studies and marketing communication approaches to the idea of what communication actually is. Indeed, as Gary Radford (2005) has pointed out in his study On the Philosophy of Communication, the transmission model has come to dominate amateur as well as professional considerations of communication. Seconding Barnett Pearce’s contention that “if you were to ask the first ten people on the street to define ‘communication’, all ten would likely give some version of what we call the transmission theory” (quoted in Radford, 2005, p. 1), Radford notes that “most people have a firm and quite unproblematic notion of communication” (p. 1) that is based around the quite “obvious” truth that communication is “a process of transmission” (p. 2). Shannon’s work was born from and meant to be applicable to solving mathematical problems in the engineering of communications technology; he was certainly not advancing a ‘theory of general communication’ in the sense of a model that could be used to explain interpersonal discourse and the vagaries of semantic interpretation. However, because Shannon’s work is grounded in the technology of communication it appeared to present a seductive (because scientifically rigorous) way of approaching the creation of a theory that could explain human communication across technologies of mass media. For a populace more and more used to thinking of communication as a function of technology, a technological model of communication appears quite natural. Electronic engineering terminology has become a part of our day-to-day lexicon: broadcast, signal, distortion, reception, tether, coverage, etc. The words have come to define our understanding of communication (both face-to-face and technologically-mediated) and they are infused with the assumptions of source, noise, receiver, and the process of transmission.

Intimately allied to the transmission model is the assumption of control that informs it. The most referenced author in Shannon’s original paper is Norbert Wiener, the founder of cybernetics. Wiener’s famous definition of cybernetics was that it was the “science of communication and control” and unlike Shannon he was far more happy to expand his work’s applicability across disciplinary boundaries, investigating the fundamental role of control in human communication and social systems. The link between Shannon and Wiener, and between the transmission communication model and cybernetics, was strengthened by two important elements: Warren Weaver’...