eBook - ePub

Archaeology of the Military Orders

A Survey of the Urban Centres, Rural Settlements and Castles of the Military Orders in the Latin East (c.1120-1291)

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Archaeology of the Military Orders

A Survey of the Urban Centres, Rural Settlements and Castles of the Military Orders in the Latin East (c.1120-1291)

About this book

First Published in 2004. Including previously unpublished and little known material, this cutting-edge book presents a detailed discussion of the archaeological evidence of the five military orders in the Latin East: the Hospitallers; the Templars; the Teutonic Knight; the Leper Knights of St Lazarus; the Knights of St Thomas. Discussing in detail the distinctive architecture relating to their various undertakings (such as hospitals in Jerusalem and Acre) Adrian Boas places emphasis on the importance of the Military Orders in the development of military architecture in the Middle Ages. The three principal sections of the book consist of chapters relating to the urban quarters of the Orders in Jerusalem, Acre and other cities, their numerous rural possessions, and the tens of castles built or purchased and expanded in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. A highly illustrated and detailed study, this comprehensive volume will be an essential read for any archaeology student or scholar of this period.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Archaeology of the Military Orders by Adrian Boas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

URBAN ADMINISTRATIVE CENTRES

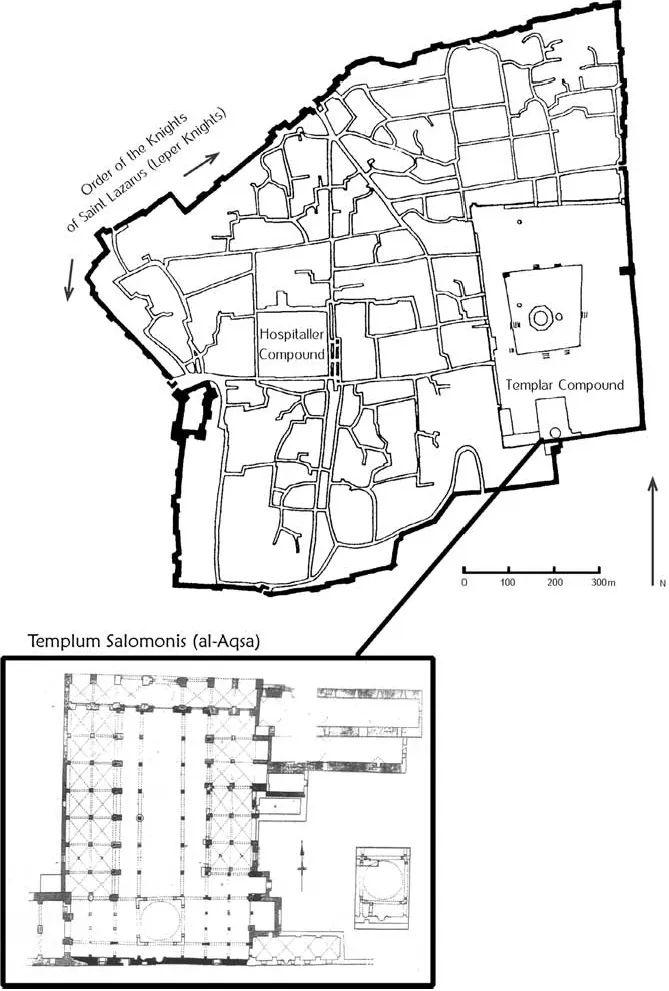

Before they began to acquire and construct fortresses and rural establishments, the Templars, Hospitallers and the smaller Order of St Lazarus already held important urban properties in Jerusalem (Figure 2). They later expanded into other cities, Acre being the principal centre of their urban activities. The Hospitallers possessed property in Jerusalem and Acre long before they became a Military Order,1 and the Order of St Lazarus had a leper hospital outside the northern wall of the Holy City. The Templars were established as a Military Order in Jerusalem with property on the Temple Mount and later acquired Quarters in Acre and possessions in other towns. The Teutonic Knights and the Knights of St Thomas of Acre, both Orders that were founded in Acre after the fall of Jerusalem in 1187, had their headquarters in the city. After the recovery of Jerusalem by treaty in 1229, the Teutonic Knights were granted property in Jerusalem which they held for the short period of Frankish rule until the final fall of the city in 1244.

Their vast resources and the important functions they fulfilled made the Military Orders an important, indeed an essential, element in Crusader urban society. They played a vital role in the economic and consequently the demographic revival of the cities, and they assumed roles in social welfare, urban politics and defence, as well as other aspects of social life.2 Their presence, in particular the presence of the Hospitallers, was one of the major contributing factors in the revival of Jerusalem after the Crusader siege and capture of the city in 1099. This conquest had been followed by the slaughter and expulsion of the entire local non-Christian population. It was the Hospitaller Order, more than any other institution in the city, which induced the economic revival and resettlement of the city by providing for the needs of pilgrims and thereby enabled them to come to Jerusalem, to spend their money there and sometimes to remain in the city. They also encouraged and participated in an expanding commerce centred on pilgrimage, including the exchange of money and the establishment of workshops and specialised markets manufacturing and selling goods specifically for pilgrims.

The role played by the Military Orders in other cities was varied, but in some cases of considerable impact. They provided the citizens with hospices and hospitals and occasionally built fortifications and took an active part in the defence of several towns.3 In some of these towns at certain times they took over the defence of whole sections of the walls, including gates, towers, barbicans and moats,4 while in others their fortresses provided refuge for the citizens in times of invasion. In some cases entire towns came into their possession: in 1152 the Templars were granted the city of Gaza and around the same time Tortosa also became a Templar possession, in c. 1260 the Hospitallers took over Arsuf in its entirety and in that year the Templars acquired Sidon. As a result of their experience and extensive connections, the Military Orders came to play an important role as advisers in matters of state and in the strategic and tactical planning of battles. They participated in war councils such as that which advocated the march on Hattin in 1187, the council held by Amaury II in 1197 which decided to attack Beirut, the council of 1210 which declined to renew the truce with Egypt, and a council discussing the refortification of Jerusalem held by Frederick II in 1229.5 Their connections with the enemy also gave them an important role as mediators and treaty negotiators.6 Naturally enough this activity also extended into local urban politics, in which they became both active participants and intermediaries in disputes between different factions in the Crusader cities. In the War of St Sabas, a violent conflict which broke out between the Italian communes in Acre in the mid-thirteenth century, the two major Orders took opposite sides, the Hospitallers supporting the Genoese camp while the Templars sided with the Venetians and Pisans. However, in the aftermath of the war they both became mediators, attempting to reconcile the opposing parties.7 The Masters of the Hospital and the Temple had particular tasks in state and urban ceremonies; their special status in Jerusalem is reflected by the fact that they were given the privilege of holding the keys to the crown jewels.8

Figure 2 Map of Crusader Jerusalem showing the Quarters of the Military Orders (inset: Templum Salomonis).

As organisations concerned with welfare, the Hospital of St John and the other hospitaller orders carried out the important task of providing care for the needy and the ill. They set up hospitals and hospices which could house hundreds of people. The Hospital of St John in Jerusalem provided medical care, though this was limited by the abilities of the medieval doctor. The Orders, however, did not have a monopoly on hospitals; most monastic establishments had an infirmary and there were also privately established hospitals. Raymond of St Gilles established a hospital for the poor (hospitale pauperum) on Mons Peregrinus in Tripoli and Count Bertrand, who followed Raymond as Count of Tripoli, gave rich endowments to this hospital.9 Near Rafaniya, further to the north, Raymond and Bertrand established a similar endowment.10 A hospital at Turbessel in the Principality of Edessa was annexed to the Church of St Romanus and was apparently endowed by Joscelin I de Courtenay and by Baldwin of Bourcq prior to his ascending to the throne of Jerusalem in 1118. On the other hand, the Military Orders’ hospitals were large, well run and available to everyone, including the large numbers of poor and ill in the cities – and even, it would seem, Muslims and Jews.11 In time the independent hospitals either disappeared or were absorbed into the Hospitaller network. On 28 December 1126 both of the establishments in the County of Tripoli were transferred to the Order of St John.12 In 1134 Joscelin ceded the hospital at Turbessel to the Hospitallers; it no doubt ceased to function with the loss of the city to Zengi in 1144.

With regard to defence, the Military Orders played an important role in strengthening and defending the walls of several of the towns in the Latin East, including Jerusalem, Acre, Arsuf, Caesarea, Gaza, Jaffa, Sidon, Tortosa, Tripoli and Tyre. The Hospitallers helped to fortify Caesarea in 1218, and the Templars and Hospitallers possibly advised Louis IX about reconstructing its defences between March 1251 and May 1252.13 The Hospitallers also appear to have been involved in the construction of the barbican (or a section of it) in Acre during the last decades of Crusader rule.14 By that time the Military Orders were the only local organisations with the financial and human resources to carry out major works of construction.

1

THE URBAN QUARTERS OF THE TEMPLARS

It is perhaps ironic that, like the Templar Order itself, the urban headquarters of the Templars have almost entirely disappeared. The irony lies in the fact that the destruction of the Templar buildings had nothing to do with the fate of the Order in the early fourteenth century.1 The destruction of the Templar Quarter in Jerusalem was carried out by Saladin in 1187 as an act of purification of the Muslim holy site. As the Temple Mount was not returned to the Franks in 1229 when the treaty signed between the Egyptian Sultan al-Kamil and Frederick II gave them control over the rest of the city, the Templars never rebuilt their quarter in Jerusalem. In Acre substantial remains of the Templar Quarter survived the Mamluk destruction of 1291, but these were dismantled with the Turkish resettlement from the middle of the eighteenth century. The Bedouin governor Dahr al-Umar used the Templar palace as a source of building stone. It was almost completely demolished by 1752 and only minor fragments have survived the destruction of the last three centuries.2 In addition, a rise in the level of the sea has inundated the area of the Templar palace.

The Templars’ Quarter in Jerusalem

In 1220, after the Order was established, Baldwin II gave the Templars a wing in the royal palace (Templum Salomonis) on the southern end of the Temple Mount. According to William of Tyre: ‘Since they had neither a church nor a fixed place of abode, the king granted them a temporary dwelling place in his own palace, on the north side of the Temple of the Lord.’3 This might seem a remarkable act, and it would be difficult to find a precedent for a king parcelling out parts of his palace in this fashion, although William of Tyre did refer to this as a temporary grant. However, the king was perhaps not particularly satisfied with the royal residence in the Templum Salomonis (the al-Aqsa Mosque), which he himself had only recently occupied and which had certainly not been built to serve as a residence. It must have been rather uncomfortable, and, as I have suggested elsewhere, he may already have been contemplating a move to a more convenient location prior to the foundation of the Templar Order.4

For the first decade of its existence the Templar Order remained static in its development, numbering no more than nine brothers.5 However, after the Council of Troyes in 1129, in which the Order received papal support, financial aid, grants and recruitment began in earnest and the Order entered a process of rapid expansion. It was probably around this time that Baldwin II, or perhaps King Fulk in the early years of his reign (1131–43), handed over the entire palace to the Templars and moved elsewhere.6 The Order was now in possession of the entire southern part of the Temple Mount, and around the middle of the twelfth century began a programme of construction which, to judge from pilgrim accounts, was to transform the area entirely. Much of this construction must date from around the sixth decade of the twelfth century, as suggested by two facts. Firstly, there is the large corpus of Romanesque sculptural decoration which may have come from these buildings, which has been dated by art historians, on analogy with contemporary works from Apulia, to the second half of the twelfth century.7 Unfortunately none of these pieces are in situ and consequently their source of origin remains unclear. More secure evidence is the fact that the Templar buildings, according to the German pilgrim John of Würzburg, were already largely standing at the time he described them in c. 1160 (or c. 1165) and the new church was under construction. His description of these buildings gives us a fairly good idea of the extent of the Templar construction works on the south side of the Temple Mount:

On the right hand [after entering the western gate] towards the south is the palace which Solomon is said to have built, wherein is a wondrous stable of such size that it is able to contain more than two thousand horses or fifteen hundred camels. Close to this palace the Knights Templars have many spacious and connected buildings, and also the foundations of a new and large church which is not yet finished.8

A similar, but much more detailed description is given by another German pilgrim, Theoderich, writing around 1169 (or 1172):

the palace of Solomon, which is oblong and supported by columns within like a church, and at the end is round like a sanctuary and covered by a great round dome so that, as I have said, it resembles a church. This building, with all its appurtenances, has passed into the hands of the Knights Templars, who dwell in it and in the other buildings connected with it, having many magazines of arms, clothing and food in it, and are ever on the watch to guard and protect the country. They have below them stables for horses built by King Solomon himself in the days of old, adjoining the palace, a wondrous and intricate building resting on piers and containing an endless complication of arches and vaults, which stable, we declare, according to our reckoning, could take in ten thousand horses and their grooms. No man could send an arrow from one end of their building to the other, either lengthways or crossways, at one shot with a Balearic bow. Above it abounds with rooms, solar chambers and buildings suitable for all manner of uses. Those who walk upon the roof of it find an abundance of gardens, courtyards, antechambers, vestibules, and rain-water cisterns; while down below it contains a wonderful number of baths, storehouses, granaries and magazines for the storage of wood and other needful provisions. On another side of the palace, that is to say, on the western side, the Templars have erected a new building. I could give measurements of its height, length and breadth of its cellars, refectories, staircase, and roof, rising with a high pitch, unlike the flat roofs of that country; but even if I did so my hearers would hardly be able to believe me. They have built a new cloister there in addition to the old one which they had in another part of the building. Moreover, they are laying the foundation of a new church of wondrous size and workmanship in this place, by the side of the great court.9

Despite some obvious embellishments, particularly in Theoderich’s account, these two sources are more informative about the Templar construction works...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Figures

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chronological Summary

- Background

- Part I: Urban Administrative Centres

- Part II: The Rural Activity of The Military Orders

- Part III: The Defence of the Latin East

- Part IV: Additional Archaeological Evidence

- Conclusion

- Appendix I: Chronology of Castles

- Appendix II: Gazetteer of Sites of the Military Orders

- Notes

- Bibliography