eBook - ePub

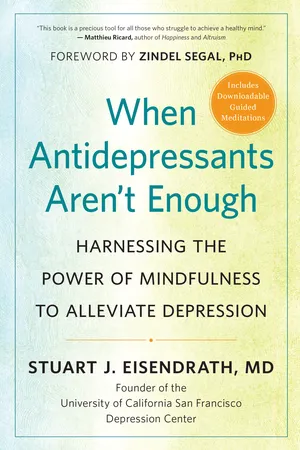

When Antidepressants Aren't Enough

Harnessing the Power of Mindfulness to Alleviate Depression

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

When Antidepressants Aren't Enough

Harnessing the Power of Mindfulness to Alleviate Depression

About this book

For nearly two decades, Dr. Stuart Eisendrath has been researching and teaching the therapeutic effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) with people experiencing clinical depression. By helping them recognize that they can find relief by changing how they relate to their thoughts, Eisendrath has seen dramatic improvements in people's quality of life, as well as actual, measurable brain changes. Easily practiced breath exercises, meditations, and innovative visualizations release readers from what can often feel like the tyranny of their thoughts. Freedom of thought, feeling, and action is the life-altering result.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access When Antidepressants Aren't Enough by Stuart J. Eisendrath in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Psychiatry & Mental Health. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1THE NATURE OF THE DEPRESSION BEAST

Whether you call depression a demon, madness, or a season in hell, it is without doubt one of the most painful human conditions. It is also widespread, and younger and younger people are experiencing its onset. Instead of starting in a person’s late twenties or thirties, as it once did, it now typically comes on in a person’s late teens or early twenties. It also affects people of all social classes and situations. People as diverse as Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Ernest Hemingway, Brooke Shields, and Gwyneth Paltrow have suffered from depression.

Mahatma Gandhi described his depression as “a dryness of the heart” that made him want to “run away from the world.”1 Vincent van Gogh described his experience in his diary: “I cannot possibly describe what the thing I have is like; there are terrible fits of anxiety — without any apparent cause — or then again a feeling of emptiness and fatigue in the mind. I consider the whole rather as a simple accident, no doubt a large part of it is my fault, and from time to time I have fits of melancholy, atrocious remorse.”2

If you have suffered from depression or are suffering right now, you know the sadness, the lack of joy, and the paralysis it can bring. It often impairs cognitive function, so that thinking and even the simplest decisions are difficult. The past looks terrible, the future promises disaster, and you may feel as if you are not worth much at all. Your sleep and appetite may be affected — either increased or decreased. You may be overcome with thoughts of death and suicide along with the feeling of being helpless to do anything about your condition. You may also feel hopeless, believing that no one else can help you. Here’s what I want you to know right now: These thoughts are just that; they are thoughts. They are not facts. And I’m going to show you how to change your relationship to these thoughts, so they stop having such a firm grip on your life.

There are various theories about depression and what causes it. Currently, our understanding is that both genetic predispositions and environmental stressors play significant roles. There is some evidence, for instance, that genetic predispositions affect how we handle stress.

From an evolutionary standpoint, it has often been thought that depression has a potential adaptive function. For example, in studies of pigtail and bonnet macaque monkeys, when infants were separated from their mother, the infants adopted what appeared to be a depressive state. They would lie on the floor, curl up, and socially withdraw. After a short cry out to the mother, if the mother did not return, this depressive state persisted. So, in this sense, the depressive state was thought to act as a means of conserving energy.

Moreover, it was postulated that the infant monkeys would try to avoid such an apparently unpleasant state by staying close to their mother whenever possible. Thus, the attempt to prevent depressive states from occurring resulted in the enhancement of the drive for attachment of the infant to the mother. In this sense, avoidance of depression served as an adaptive survival value for the infants, keeping them safely attached and under the protective purview of their mothers.3

The evolutionary hypothesis for depression is one of many that we consider today. Another causative factor is thought to be stress. The pace of everyday life has increased; coping with modern time pressures and information input can be challenging. An additional form of stress relates to our society’s social fabric. As we’ve become a more mobile society, many of the established social supports, such as having family nearby, have dropped away. When these stresses are experienced along with traditional factors such as grief and trauma, the results are compounded. Biological factors such as genetics, neural transmitters, and brain circuitry also play key roles.

Our understanding of depression has been deepened in recent years by the investigation of brain functioning using moment-to-moment scanning such as positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).4 These techniques have revealed alterations of brain circuitry in people with depression and suggested that recovery may be associated with restoring more normal patterns of brain activation. These investigations have helped to shed light about what areas of the brain are most involved in depression and how interventions can be targeted toward those areas. For example, antidepressants and electrical or magnetic brain stimulation may be used to normalize altered patterns of activation. As we will discuss later, mindfulness interventions such as MBCT may have powerful brain impacts of their own.

Depression Is Not a One-Time Event

One thing we know for sure: depression tends to be chronic and recurrent. It is not a disease like pneumonia that happens once and then (usually) never happens again. It is more like asthma; you can expect to have episodes intermittently throughout your life. You must understand this vital point, so that when depressive episodes hit, you see them for what they are: recurrences of your illness and not personal weakness or moral failure.

With depression, the chance of having a recurrence increases with the number of episodes you’ve had. For example, with one episode, there is up to a 30 percent chance of recurrence within ten years. With three episodes, the likelihood of having a recurrence within that same time frame is 90 percent. The ability to “recover” from a depression does offer the best chance of preventing further episodes, and people can go for substantial periods of time without recurrence, but depression is not typically cured, and even in remission people may have lingering symptoms. Because of the likelihood of recurrence, I want you to have and know how to use the tools that MBCT can provide both to keep depression at bay and to deal with depressive symptoms when they arrive.

When depressive episodes hit, you must see them for what they are: recurrences of your illness and not personal weakness or moral failure.

But let’s be clear. Although remission is often portrayed in rather glowing terms in pharmaceutical advertisements, it is not easily achieved. In fact, failure to achieve full remission shows the tenacity of your illness. It is typical, and it is not a personal weakness. Of course, not achieving remission occurs with other illnesses as well. Not many people achieve remission with medical conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or chronic lung disease. Like depression, these illnesses tend to be chronic. That is why our modified MBCT approach is aimed at the illness rather than only a single episode.

The largest and longest study of depression ever completed at the National Institute of Mental Health, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, investigated different approaches to depression treatment.5 In the study, the initial treatment consisted of administering a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), the most commonly utilized class of antidepressant, for twelve weeks. The remission rate was 28 percent after this first treatment. If individuals did not achieve remission after that one antidepressant trial, they were given another antidepressant trial, an augmenting agent, or traditional cognitive therapy.

After this second step, the cumulative remission rate was approximately 50 percent. This meant, however, that half of the people had not achieved remission despite twenty-four weeks of monitored treatment in the study. After two additional twelve-week interventions (making a total of forty-eight weeks of treatment), only 43 percent of individuals were in remission, including participants who achieved remission but then suffered a relapse. These results illustrate the challenges facing those with depression.

This book is not written to denigrate antidepressants or traditional therapy. They can be lifesaving at times. But they have their limits, a point that applies to other forms of psychotherapy as well.

For example, for a number of years I taught cognitive therapy groups for individuals with chronic depression. In traditional cognitive therapy, negative thoughts (cognitions) are considered to be an important driver of depressed mood, and individuals are taught to challenge them. In this model when individuals express a negative belief or thought, they are encouraged to develop a more balanced or alternative thought. But this may be particularly difficult when individuals have suffered chronic depression lasting two or more years. Some people simply find it too difficult to counter their negative thoughts and beliefs.

If you have suffered depression for some time, I’m sure you get it. It is likely that you believe you have strong evidence to support your negative thoughts and beliefs due to many years of experience in interpreting yourself and your environment in a negative way. If you have been depressed for years (in our research, the Practicing Alternatives to Heal from Depression study, PATH-D, which is described in detail in Appendix A, participants averaged seven years of depression for their current episode), I’m sure you have accumulated quite a bit of evidence to support your pessimistic thinking. That’s in large part because depression has a tendency to put a negative filter on memory and experiences. For example, if we have been rejected in one social situation, we typically expect further rejections, often blaming ourselves for the rejection. It’s really hard to counter that with alternative thoughts.

Enter Mindfulness

The unique form of meditation that is mindfulness meditation offers a different approach. Other types, such as Transcendental Meditation and some forms of Judeo-Christian meditation, are concentrative; they focus on a particular phrase or word. Mindfulness meditation differs in that it is intentionally fixed on a focus the meditator chooses. For example, it may be focused on the breath moving in and out of the nostrils, bodily sensations, thoughts, or feelings. It allows meditators to observe themselves participating in experiences in real time, as those experiences are occurring. Mindfulness meditation is sometimes referred to as insight meditation, as it allows meditators to see things as they really are.

Mindfulness meditation traces its roots to Buddhist practices of twenty-five hundred years ago. The Buddha is said to have utilized his own mindfulness practices, including sitting and walking meditations. Over the centuries, mindfulness meditation has spread beyond its Asian beginnings. Modern mindfulness meditation can be traced to the Theravada tradition of Buddhism in the eighteenth century, where the meditative component of Buddhism was emphasized. In the mid-twentieth century Mahasi Sayadaw began to change the focus of meditation to center on a present-moment awareness of the sensations in the body, which is typically done through an exercise called the body scan.6 The mindfulness practice was further secularized and given a broader audience when Jon Kabat-Zinn introduced his Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program at the University of Massachusetts at Worcester in 1979, which was built around the principles he later elucidated in his classic book Full Catastrophe Living.7

The MBSR program offered a way for a large number of people to explore mindfulness unhindered by religious or philosophical concepts. The program offered an eight-week course that facilitated empirical research regarding its efficacy. The program proved beneficial for a wide variety of conditions, such as chronic pain, heart disease, cancer, psoriasis, anxiety, and generalized stress.8 As a condensation of mindfulness practices into a discrete program, MBSR appealed to a wide-ranging audience. Importantly, it offered a platform that could be built upon for specific applications. In fact, it was the forerunner of the MBCT program as well as other mindfulness-based interventions. MBCT bears many similarities to MBSR, such as utilizing comparable meditation practices. MBCT differs by being more focused on depression and anxiety in contrast to MBSR’s broader scope.

Mindfulness is focused on the present moment. You incline your mind to focus on something that is occurring right now. Often you may begin with focusing on the breath moving in and out, perhaps at the nostrils but at other times in the chest or abdomen. The breath is a neutral object of attention for most people and is always present during life. Breathing can be experienced with little thought or effort. It is naturally tied to the present moment — typically you don’t spend much time focusing on your last breath or the upcoming one.

Many meditations start with the breath and then shift to another object of attention. For example, with the body scan, you typically start with the breath and then investigate the senses in areas of the body, starting in one limb and moving progressively throughout the body. But you do not need to begin with the breath in every meditation.

Mindfulness meditation is like a spotlight that you can choose to direct anywhere you want. It puts a bright light on the object of attention. You can aim it at physical sensations, but also at thoughts that are emerging or at feelings that are present. You can even choose “open awareness,” in which you shine the spotlight on whatever arises in your consciousness. Although mindfulness meditation may be relaxing, it is aimed at producing awareness. In other words, it is aimed at falling awake, not asleep. But if you try a meditation and find yourself falling asleep, in keeping with the mindfulness approach you are to be accepting of that, not critical. Kindly self-compassion is central to mindfulness.

When you begin building your practice, several suggestions may be helpful. One is to use a quiet place where you won’t be disturbed. Another is to build regularity into your practice by doing it at the same time each day. You can experiment with what time works best for you. Some people prefer to start their day with meditation, while others prefer it in the middle or at the end of the day. The meditative process is...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: When Antidepressants Aren’t Enough

- 1. The Nature of the Depression Beast

- Part I: The Power of Now

- Part II: Changing Your Relationship to Your Mind and Thoughts

- Part III: Stumbling Blocks to Change and How to Overcome Them

- Part IV: Lasting Ways to Achieve Happiness

- Appendix A: Clinical Research Results

- Appendix B: Research Results and Brain Effects

- Acknowledgments

- Permission Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index

- About the Author