CHAPTER ONE

A Strategy-Based Framework for Extending Brand Image Research

David M. Boush

University of Oregon

Scott M. Jones

Clemson University

Frameworks for assessing competitive advantage (Day & Wensley, 1988) describe the brand image as a resource, a possible source of advantage. It is a resource that managers have long understood to be important. Aaker (1989) reported a study where, out of 32 potential strategic competitive advantages, managers ranked reputation first and name recognition third in importance. Recent activities in the marketplace show an increased interest in brand image as a resource both by reliance on brand extension for growth and by acquisition of well-known consumer brand names (Aaker & Keller, 1990; Tauber, 1988). Clearly it is not the brand name itself that provides a resource to be managed but the mental representation that has come to be known as brand image. Although the concept of brand image is among the most central in marketing, marketers are hard pressed to agree on what the term means (Dobni & Zinkhan, 1990), and its literature is characterized by a variety of interesting empirical findings predicated on a diverse array of conceptual frame-works. For example, the brand image has been described as a category (Boush, 1993a, 1993b; Boush & Loken, 1991), a schema (Bridges, 1990), and part of a belief hierarchy (Reynolds & Gutman, 1984). Taken individually, these structure-based perspectives offer theoretical consistency; however, many questions relevant to managing the brand are never addressed. The literature on brand image is also characterized by a narrow focus on the brand images held by consumers, excluding the way a brand image may influence decisions made by competitors, retailers, and other stakeholders. The purpose of this chapter is to synthesize what we know about brand image and to provide an integrated framework for conducting additional research. Such a framework should be comprehensive in the sense that all important elements of brand image can be included within it and fruitful in its suggestion of untested relationships. The focus throughout this chapter is on what brand image can do for the firm. With that perspective in mind, a model is presented that relates the content and structure of brand image to the strategic functions brand image performs. After defining brand image, the model is presented first in an overview and then with a description of its components in greater detail. Because the focus of this chapter is the strategic functions brand image can serve, those functions are described first. From that point the components of the model are described so as to trace the content and structure of brand image back to its sources. The implications of changing brand image, and of explicitly considering market segments, then will be discussed. The final section will summarizes what we know and what we need to know about brand image to manage it better.

BRAND IMAGE DEFINED

A brand is widely defined as a “name, term, sign, symbol, or design or combination of them which is intended to identify the goods or services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competitors” (Kotler, 1991, p. 442). Each of these components can prove to be crucial in laying the groundwork for the brand of a firm and its identity. A great deal of study has focused on the development of a strong brand (Aaker, 1991, 1996). Many of these studies are concentrated on brand development within traditional industries and product lines. However, as noted in several chapters in this book, the need for recognizing, developing, and managing a brand image is of importance to services, products, philanthropic organizations, geographic locations, athletes, and celebrities. We follow Newman’s (1957) definition that “a brand can be viewed as a composite image of everything associated with it” (See page). More narrow definitions, such as those that confine brand image to the intangible or symbolic (e.g., Gardner & Levy, 1955) omit some brand associations (e.g., with quality or product function) that form a basis for strategic advantage.

A point that must be made explicit at the outset is that, because brand image is a mental construct, there are as many brand images as there are perceivers (Bullmore, 1984). When we speak of a brand image, we refer to the extent to which perceptions overlap across individual consumers, competitors, channel intermediaries, or others who are influenced by the brand image.

OVERVIEW OF THE MODEL

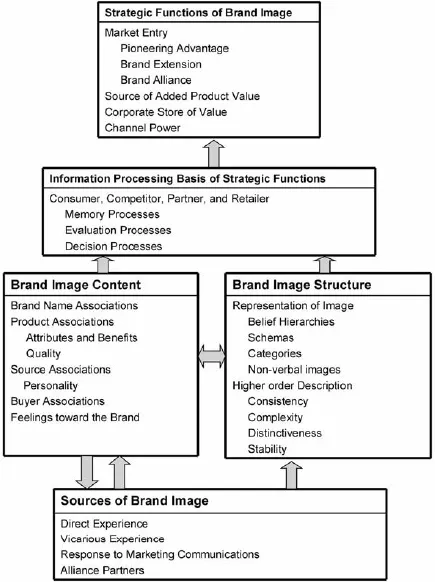

The main components of the model are: (a) the sources of brand image, (b) the content of brand image, (c) the structure of brand image, (d) the uses of brand image in stakeholder decision-making, and (e) the key strategic functions brand image performs for the firm (see Fig. 1.1). Based on experience, marketing communications, and associations from brand partners, individuals form mental impressions that we call the brand image. This image can be described in terms of both its content and its structure. The content includes the brand name, product associations, source associations, buyer associations, and feelings (i.e., affect). Frameworks for understanding brand image structure include belief hierarchies, categories, schemas, and nonverbal images. As we present later, it also is useful to discuss the structure of brand image using higher order descriptors such as consistency, complexity, stability, and distinctiveness. The arrows connecting the boxes in Fig. 1.1 indicate direct influence relations. Brand image sources influence, or create, brand image content and structure. Brand image content can influence its sources, for example, by providing expectations that may influence both the processing of advertising and product experience. Brand image content also influences its structure. For example, image consistency results from product attributes being perceived as highly correlated. Reciprocally, image structure can influence its content. For example, the perception that the products or product attributes of a brand are highly correlated may lead to beliefs about production expertise (Keller & Aaker, 1992). Both the content and the structure of brand image (which collectively amount to brand knowledge) influence the memory, evaluation, and decision processes that underlie consumer, competitor, and channel member actions and ultimately support the strategic functions of market entry, added product value, corporate store of value, and channel power. The ability of advertising to influence the strategic functions of brand image is mediated both by the brand image itself (i.e., content and structure) and by the processes by which it is used (i.e., information processing). Although the present model can apply to services, retail establishments, or industrial products, for simplicity the examples here emphasize manufacturer brands of consumer products.

FIG. 1.1. Strategic model of brand image.

THE FUNCTIONS OF BRAND IMAGE

Market Entry

Perhaps the most important functions of brand image center on market entry. Brands can permit a firm to enter a new market and simultaneously can inhibit market entry by competitors. Pioneering advantage, brand extension, and brand alliance are three important ways to gain and hold a place in the market.

Pioneering Advantage. Many of the strongest brand names (General Electric, Coca Cola, Hallmark) were among the first to be strongly associated with their respective product categories. Brand images allow firms to cement first mover (i.e., pioneering) advantages (Bain, 1956; Urban, Carter, Gaskin, & Mucha, 1986). The first brand to enter a market can occupy the best position, leaving less desirable positions for later entrants. If these later entrants want to compete for the same position they must offer something unique (e.g., lower price). Taking on the pioneering brand can be even more difficult if the cost of switching to a new brand is high, either because trying a new brand is costly or because of knowledge that is specific to using the pioneer’s product. Products without a brand identity, such as unbranded commodities, cannot protect first-mover advantage in this way. Yet the success of brands such as Orville Redenbacher prove that a brand image can be a powerful resource in product categories once thought to be relatively homogeneous.

Brand Extension. Brand images also allow firms to leverage customer franchises developed in one product market into another through brand extension (Aaker, 1989; Aaker & Keller, 1990; Boush & Loken, 1991; Tauber, 1988). Brand extension strategies have become increasingly attractive as a way to reduce the tremendous cost of new product introduction. General Electric, for example, brands a remarkable range of products, from light bulbs to jet engines. Other brands have much more narrow brand images. For example, Coca Cola’s extensions consist primarily of various colas. A question that recurs throughout this paper is whether brand images are stronger if narrow and simple or broad and complex.

Brand Alliances. One of the most popular new strategies for leveraging brand image is through a brand alliance. A brand alliance may best be described as the short-or-long term association or combination of tangible and intangible attributes associated with brand partners (Rao & Ruekert, 1994). One of the most popular types of brand alliances is a cobrand partnership. A cobrand is defined as the placement of two brand names on a single product or package (Lamb, Hair, & McDaniel, 1998; Shocker, 1995). Aaker (1996) identified two categories of cobranded products: ingredient and composite. An ingredient cobrand is characterized by the combination of tangible products associated with each partnering brand in the formation of a new product. Examples of ingredient cobrands presently in the marketplace include the Pillsbury Oreo Bars Baking Mix, Sugar-Free Kool Aid with Nutrasweet and Gateway computer with the Intel Pentium processor. A composite cobrand alliance involves the combination of less tangible brand image associations. An objective of composite cobranding is to suggest the enhancement of nonproduct-related attributes such as user and usage imagery (Keller, 1993) or experiential and symbolic benefits (Park, Jaworski, & MacInnis, 1986). Examples of composite cobrands presently in the marketplace include the Eddie Bauer edition of the Ford Explorer, Kellogg’s Disney line of cereals and the L. L. Bean version of the Subaru Outback.

Source of Added Product Value

Virtually since Gardner and Levy (1955) first discussed brand image, marketers have recognized that the brand image not only summarizes consumer experience with the products of a brand, but can actually alter that experience. For example, consumers have been shown to perceive that their favorite brands of food or beverage taste better than those of competitors in unblinded as compared with blinded taste tests (Allison & Uhl, 1964). Brand image thus becomes a way to add value to a product by transforming product experience (Aaker & Stayman, 1992; Puto & Wells, 1984). One definition of brand equity is the added value with which a brand endows a product (Farquhar, 1989). Similarly Simon and Sullivan (1990) define brand equity as “the incremental cash flows which accrue to a branded product over and above the cash flows which would result from the sale of a product with no brand name” (See page).

Corporate Store of Value

The brand name is a store of value for the accumulated investments of advertising expenses and maintenance of product quality. Firms can use this store of value to convert a strategic marketing idea into a long-term competitive advantage. For example, the Hallmark brand image benefitted from a decision made during the 1950’s to sponsor a few high-quality television specials each year. The emphasis in considering brand image as a store of value is its management as an asset over time. The central questions thus revolve around actions that increase or diminish brand store of value.

Channel Power

A strong brand name provides both an indicator and a source of power in a channel of distribution. Consequently brands are not only important for their effect horizontally, in outperforming their competitors, but vertically, in acquiring distribution and maintaining control of the terms of trade (Aaker, 1991; Porter, 1974). For example, Coca Cola’s brand extension strategy arguably accomplishes three functions at once. Extension permits market entry at lower cost, inhibits competition by tying up shelf space, and may also provide leverage in negotiating terms of trade.

Brand image may also provide companies with unique distribution outlets. For example, dual branding is a term used to describe a brand alliance characterized by the association of two brands (Levin & Levin, 2000). Examples of this type of brand alliance include Kentucky Fried Chicken and A&W sharing a retail outlet and Federal Express shipping services inside a Kinko’s copy center. Dual brand partnerships may allow companies to share expenses associated with the retail location (e.g., rent and equipment) and promotion.

THE INFORMATION-PROCESSING BASIS OF BRAND IMAGE FUNCTIONS

The accomplishment of all strategic functions depends on the way a brand image influences the information processing that underlies decisions made by consumers, competitors, and other channel members. The nature of these decisions is, of course, different for each type of stakeholder. This section describes the way brand memory, evaluation, and choice processes support strategic brand functions. Because virtually all the research on brand information processing has focused on the consumer, consumer memory, evaluation, and choice are described first. Then we discuss how brand-related information processing may influence decisions made by other channel members and competitors.

Memory Processes

Both recall and recognition may play a role in the process leading to brand choice, and the nature of their effects on choice depends on the circumstances of the choice decision. Consumers are sometimes faced with choices in which they must remember some or all of the alternatives (Lynch, Marmorstein, & Weigold, 1988). One recall mechanism that seems directly relevant to the function of brand image as a barrier to competitive entry involves the way attention to a given brand name inhibits recall of competing brands (Alba & Chattopadhyay, 1985). When a particular brand is brought to attention, either directly or because of contextual factors, it becomes more difficult to recall other brands in the same product category. If the probability of a brand being included in the choice set increases relative to its competitors, then the probability that the brand will be chosen increases (Nedungadi, 1990).

Alternatively, if the choice is made where a great deal of relevant and credible information about choice alternatives is available externally, then recognition may be used to make the choice (Bettman, 1979). However, brand recognition, defined as “the extent to which the buyer knows enough about the criteria for categorizing, but not for evaluating and distinguishing it from other brands in its product category” (Howard, 1989, p. 30), is more properly described as a precursor to the evaluation processes that are described next.

Evaluation Processes

A number of models in consumer research suppose that consumers form a positive attitude toward a product before purchasing it (Bettman, Capon, & Lutz, 1975). Following Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), attitude is defined as the location of the product on an affective dimension, such as liking. Evaluation processes are central to the accomplishment of strategic brand image functions to the extent that product evaluations are necessary prior to purchase and that brand image is evoked in product evaluations. Recent models of evaluation (Boush & Loken, 1991; Fiske & Pavelchak, 1986) suggest that people form attitudes toward products using two kinds of evaluation processes. One kind of process involves making inferences and combining individual attributes in some way; the other involves matching an object with a known category. For the former, there is extensive evidence suggesting that consumers actively construct and reconstruct brand associations in memory (Huber & McCann, 1982). One aspect of this constructive process is the way brand names can alter the context for thinking about product categories. For example, Schmitt and Dubé (1992) reported that a brand name (e.g., McDonald’s) can modify a product category (e.g., amusement parks) to create original conceptual combinations (e.g., rides shaped like golden arches). Park, Jun, and Shocker (1996) examined brand alliances as composites of two names (Godiva cake mix by Slimfast and Slimfast cake mix by Godiva) and found interesting effects based on the order each brand name was presented in the name of the product....