eBook - ePub

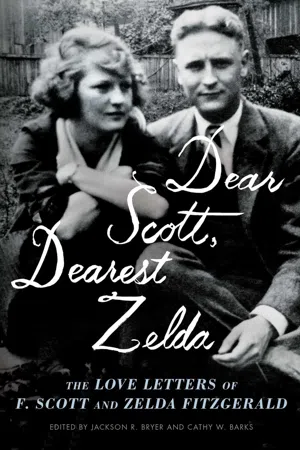

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda

The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda

The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald

About this book

“Pure and lovely…to read Zelda’s letters is to fall in love with her.” —The Washington Post

Edited by renowned Jackson R. Bryer and Cathy W. Barks, with an introduction by Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald's granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan, this compilation of over three hundred letters tells the couple's epic love story in their own words.

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald's devotion to each other endured for more than twenty-two years, through the highs and lows of his literary success and alcoholism, and her mental illness. In Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda, over 300 of their collected love letters show why theirs has long been heralded as one of the greatest love stories of the 20th century.

Edited by renowned Fitzgerald scholars Jackson R. Bryer and Cathy W. Barks, with an introduction by Scott and Zelda's granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan, this is a welcome addition to the Fitzgerald literary canon.

Edited by renowned Jackson R. Bryer and Cathy W. Barks, with an introduction by Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald's granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan, this compilation of over three hundred letters tells the couple's epic love story in their own words.

Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald's devotion to each other endured for more than twenty-two years, through the highs and lows of his literary success and alcoholism, and her mental illness. In Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda, over 300 of their collected love letters show why theirs has long been heralded as one of the greatest love stories of the 20th century.

Edited by renowned Fitzgerald scholars Jackson R. Bryer and Cathy W. Barks, with an introduction by Scott and Zelda's granddaughter, Eleanor Lanahan, this is a welcome addition to the Fitzgerald literary canon.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda by F. Scott Fitzgerald,Zelda Fitzgerald, Jackson R. Bryer,Cathy W. Barks, Jackson R. Bryer, Cathy W. Barks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Courtship and Marriage: 1918–1920

The good things and the first years . . . will stay with me forever. . . .

—SCOTT TO ZELDA, APRIL 26, 1934

Scott and Zelda first met in Montgomery, Alabama, Zelda’s hometown, in July 1918, probably at a country club dance. Zelda, who had just graduated from high school and was still the town’s most popular girl, turned eighteen that month; Scott, who had attended Princeton and was now a lieutenant in the infantry, would be twenty-two that fall. In her autobiographical novel, Save Me the Waltz (1932), Zelda recalled that Scott, so handsome in his tailor-made Brooks Brothers uniform, had “smelled like new goods” as she nestled her “face in the space between his ear and his stiff army collar” while they danced (Collected Writings 39). Just two months later, Scott recorded in his Ledger the event that would shape the rest of his life and much of his work: “Sept.: Fell in love on the 7th”(Ledger 173). That same month, Scott summed up his twenty-first year: On his birthday, he wrote, “A year of enormous importance. Work, and Zelda. Last year as a Catholic” (Ledger 172). The major decisions that a young man coming of age makes—matters of vocation, love, and faith—had been decided.

Scott, although still untried and immature in many ways, had adamantly committed himself to becoming “one of the greatest writers who ever lived” (as he told his college friend Edmund “Bunny” Wilson) and to having the “top girl” at his side to share the storybook life he envisioned. During his years at Princeton University, his academic life had taken a backseat to his social ambitions; realizing that he probably would never graduate, Scott had enlisted in the army in October 1917. His military training eventually brought him to Camp Sheridan, near Montgomery, and to Zelda—the most beautiful, confident, and sought-after girl in town. Scott then devoted himself to becoming the “top man” among her many suitors, intending to vanquish the other young college boys and soldiers by marrying this most desirable girl.

Zelda, being younger, was less clear about particulars, but she certainly shared Scott’s romantic sense of a special destiny. Other than teaching, careers for women were still discouraged. Courtship and marriage were the areas in which young women such as Zelda, the daughter of a prominent judge, were expected to achieve distinction. Her three older sisters, Marjorie, Rosalind, and Clothilde, were already married; Zelda intended to make the absolute most of her own days as a southern belle, relishing her role in the spotlight. Montgomery may have been a small, provincial city, but it was surrounded by college towns, as well as being crowded with young soldiers from nearby training camps. The war imbued the local courtship rituals with an even greater sense of urgency and romanticism than usual. The crowds of young people necessitated numerous forms of entertainment—parties, dances, sports, plays, and Friday-night vaudeville shows—to keep them occupied. The Sayres’ front porch, replete with every sort of southern flower and a porch swing for Zelda and her beaux, was locally famous. Zelda had already filled a glove box with the small colorful badges of masculine honor the young soldiers took from their uniforms and gave to her as tokens of their affection. Scott soon added his own insignia to this collection. Young aviators from Taylor Field executed dangerous stunts as they flew their airplanes over Zelda’s house to impress her. Scott competed with such exploits by bragging about the famous writer he was going to become. Although Scott did not “get over” to fight the war, that summer and fall, as he vied for Zelda’s heart, the two no doubt believed that he would be sent overseas and perhaps face death. He continued to write, hoping that in the event of his death, he would become the American counterpart of Rupert Brooke, the handsome young English poet, who in death had become the romantic hero— forever young, beautiful, and full of promise.

The war, however, ended just as Scott was preparing to embark for France. When he was discharged in February 1919, he went to New York City to find a job and to become a famous living writer, instead of a dead one. He hoped to find work with a newspaper but had to settle for a low-paying job with an advertising firm. He missed Zelda terribly, told his family about her, and asked his mother to write to Zelda, which she did. Then, on March 24, Scott sent Zelda the engagement ring that had been his mother’s. Zelda couldn’t have been more thrilled. But although her letters are full of enthusiastic assurances of her love, her life in Montgomery continued pretty much the same as before—a whirlwind of social engagements, which included continuing to go out with other boys—and she wrote Scott all about it. Zelda especially loved the rounds of college parties, dances, and commencement activities beginning in May and the exciting football weekends in the fall. Scott’s daily life, on the other hand, was at total odds with his idealized conception of himself. He hated his job, hated having so little money, and especially hated how his clothes were becoming threadbare. And, worse yet, his stories weren’t selling. Later, in “My Lost City” (1936), he would look back and write, “. . . I was haunted always by my other life . . . my fixation upon the day’s letter from Alabama—would it come and what would it say?—my shabby suits, my poverty, and love. . . . I was a failure— mediocre at advertising work and unable to get started as a writer” (Crack-Up 25–26).

Despite his sense of failure, Scott was actually quite productive. Although he sold only one story in the spring of 1919—“Babes in the Woods,” for which The Smart Set paid him thirty dollars—he continued his apprenticeship and produced over nineteen stories that winter and spring. All were rejected by the magazines to which he submitted them; many, however, were later revised and published. Although Scott was being unrealistic in his expectations of immediate fame—who, after all, is a blazing success at the age of twenty-two?—his sense of failure, anxiety, and loss was keen and would remain with him the rest of his life. When Scott visited Zelda in Montgomery in mid-April, he was depressed and losing confidence in himself. Zelda tried to reassure him in her letters, but she also continued to report on all the fun she was having.

By June 1919, Scott and Zelda’s engagement was in serious jeopardy. When Scott received a note that Zelda had written to another suitor and then accidentally put into the wrong envelope, one addressed to Scott, he was enraged and ordered her never to write to him again. But as soon as he received Zelda’s brief explanation, he went to Montgomery and begged her to marry him right away. Zelda cried in his arms, but she turned him down and broke the engagement. Scott returned to New York feeling utterly defeated as a writer and a lover. He wrote to a friend: “I’ve done my best and I’ve failed—it’s a great tragedy to me and I feel I have very little left to live for. . . . Unless someday she will marry me I will never marry” (Letters 455–456). He quit his job, went on a three-week bender, returned to his parents’ home in St. Paul, and went to work revising “The Romantic Egotist,” the novel that had been rejected by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1918. During this period of a little over two months, Scott and Zelda exchanged no letters. But when Scribners accepted his novel, now entitled This Side of Paradise, on September 16, 1919, Scott immediately wrote to Zelda again and planned a visit to Montgomery; the couple soon resumed their engagement. More letters and visits to Montgomery followed, and Zelda and Scott were married the following April, only one year after Scott had first sent Zelda the engagement ring.

In his imagination, Scott attached the acquisition of Zelda to the acquisition of material success, thereby identifying what were already the twin themes of his writing—love and money—as the twin themes of his life, as well. Later, he looked back on the summer of his broken engagement in “Pasting It Together” (1936) and wrote, “It was one ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Editors’ Note

- Introduction

- Part I: Courtship and Marriage: 1918–1920

- Part II: The Years Together: 1920–1929

- Part III: Breaking Down: 1930–1938

- Part IV: The Final Years: 1939–1940

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Index

- Copyright