eBook - ePub

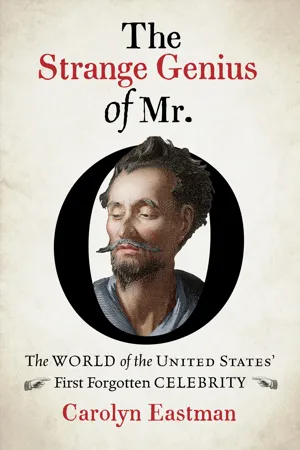

The Strange Genius of Mr. O

The World of the United States' First Forgotten Celebrity

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Strange Genius of Mr. O

The World of the United States' First Forgotten Celebrity

About this book

When James Ogilvie arrived in America in 1793, he was a deeply ambitious but impoverished teacher. By the time he returned to Britain in 1817, he had become a bona fide celebrity known simply as Mr. O, counting the nation’s leading politicians and intellectuals among his admirers. And then, like so many meteoric American luminaries afterward, he fell from grace.

The Strange Genius of Mr. O is at once the biography of a remarkable performer — a gaunt Scottish orator who appeared in a toga — and a story of the United States during the founding era. Ogilvie’s career featured many of the hallmarks of celebrity we recognize from later eras: glamorous friends, eccentric clothing, scandalous religious views, narcissism, and even an alarming drug habit. Yet he captivated audiences with his eloquence and inaugurated a golden age of American oratory. Examining his roller-coaster career and the Americans who admired (or hated) him, this fascinating book renders a vivid portrait of the United States in the midst of invention.

The Strange Genius of Mr. O is at once the biography of a remarkable performer — a gaunt Scottish orator who appeared in a toga — and a story of the United States during the founding era. Ogilvie’s career featured many of the hallmarks of celebrity we recognize from later eras: glamorous friends, eccentric clothing, scandalous religious views, narcissism, and even an alarming drug habit. Yet he captivated audiences with his eloquence and inaugurated a golden age of American oratory. Examining his roller-coaster career and the Americans who admired (or hated) him, this fascinating book renders a vivid portrait of the United States in the midst of invention.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Strange Genius of Mr. O by Carolyn Eastman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Biografías históricas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

{ CHAPTER 1 }

The Ogilviad; or, Two Students at King’s College Fight a Duel in Poetry,

1786–1793

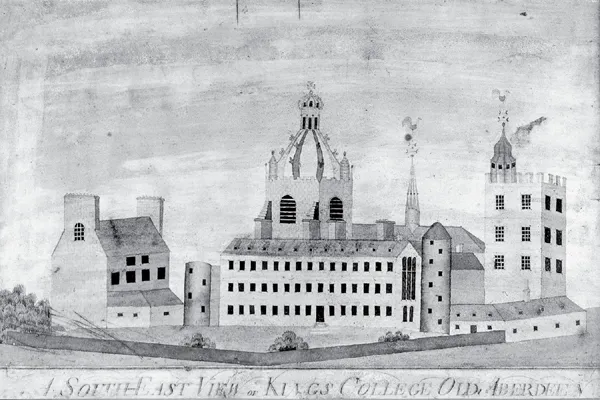

The fight began on the grounds of King’s College in Aberdeen on the far northeastern coast of Scotland. It was winter. This close to the Arctic Circle, Aberdonians ate their breakfast of bread with milk in the dark, saw morning light emerge sometime before nine in the morning, and found the sun fading by three in the afternoon. In fact, they probably wouldn’t have used the word sun at all, because no one knew better than the Scots how many winter days saw nothing but heavy clouds and cold, wet precipitation. Aberdeen was often called the Grey City for the locally quarried gray granite used to build the city’s homes, businesses, and municipal buildings; its winter days with its half-lit skies made this landscape appear in grayscale only—and against this backdrop, the college boys’ red gowns appeared like targets. The temptation to hurl a snowball or stuff a wad of cold, wet slush down the back of another boy’s gown could be overwhelming.

Conflicts between the students were so common that the college had installed elaborate rules to punish the offenders. Even the choice of red gowns was intentional. Nearly a century earlier the British Parliament had insisted that all Scottish college students wear scarlet gowns to discourage bad behavior, reasoning that the color made the boys hard to miss in a crowd; “therby the students may be discurraged from vageing or vice.” A glimpse at the lists of rules suggests, however, that putting them in scarlet had not solved the problem. A few years before James Ogilvie arrived at King’s, the students had rioted. Most of the students ranged between the ages of thirteen and nineteen—in the 1780s, college students in both Britain and America usually finished by their late teens—and fighting was endemic. If the college had caught Ogilvie fighting with Grigor Grant, the boys would have received fines, and Ogilvie, at least, didn’t have the money to spare.1

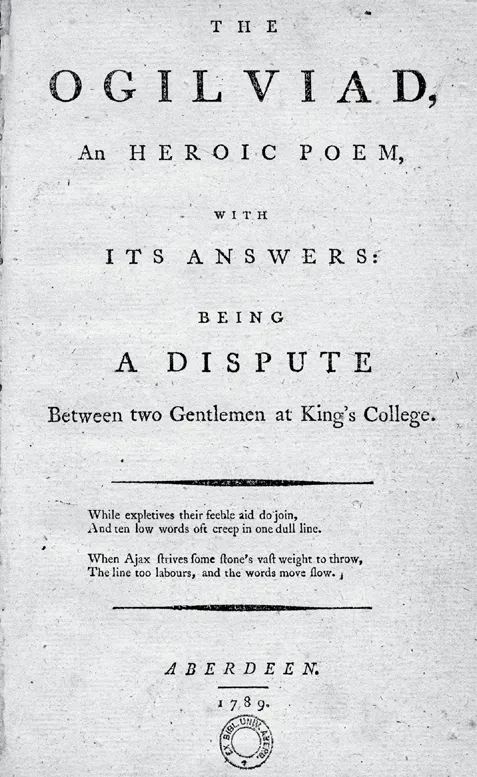

Why sixteen-year-old Ogilvie knocked Grigor Grant into the snow has been lost to history. But we do know how the fight proceeded, because rather than follow through with fists the two boys decided to continue their fight in poetry. By the end, they were so pleased with themselves that they published their poem with a grandiose title: The Ogilviad, or song of Ogilvie, a title that mimics Homer’s The Iliad (song of Ilion). But if The Iliad told of great battles, The Ogilviad is itself a battle. The two teenaged authors took turns insulting each other and claiming superior wit and intelligence for themselves rather than recounting heroic feats. In attack-and-reply fashion, they mocked each other’s intelligence, poetic skill, clothing, and hygiene. It is, in essence, an eighteenth-century duel fought at ten syllables per line.

Reading The Ogilviad reveals more than just the Scottish youth of a man who would eventually become celebrated in the United States. This document illuminates the power of words during an age of revolutions. Grant and Ogilvie wrote it to show off their linguistic chest-puffing, but along the way they demonstrated their ambitions using the syntax they learned from their college classes: ambition robed in the language of Greek heroes, the panache of Roman orators, and the slashing wit of early eighteenth-century British poets. Neither of these teens came from privilege, and both knew their opportunities after graduation were limited. Learning to speak and write with eloquent power could raise their chances. Their educations taught them to dream of displaying their talents and rising to positions of public importance, all on the basis of their power with words. The Ogilviad is only sixteen pages long, but it opens up a larger world of the marriage between eloquence and ambition.

A Poem now presents itself to view,

Replete with many wonders strange and true;

Ye critics, stare not, nor with partial eye

View the prowess of great Ogilvie.

These lines by Grigor Grant opened the poem and set its tone and could easily be mistaken as serious. But the italics referring to “great Ogilvie” were intended to signal sarcasm, not admiration. Although the title seems to invoke Homer’s epic, actually the two boys mimicked Alexander Pope’s mock-heroic poem, The Dunciad (1728–1743, or song of the Dunce), a classic of literary satire well known to readers of the day. Pope wrote the poem to attack his critics, characterizing them as a confederacy of dunces and hacks who worshipped the goddess Dullness and sought to flood the nation with stupidity and tastelessness. The Dunciad proved wildly influential, prompting more than two hundred imitators over the decades who used titles ending with -iad and deployed withering mockery to goad their enemies and establish themselves as talented wits. The vogue even crossed the Atlantic, leading to a Jeffersoniad in 1801 and two Hamiltoniads, both published in 1804, among others. When these two boys published their Ogilviad, none of their readers would have missed the debt to Pope’s poem.2

In the hands of an author like Pope, the weapon of poetic satire could be merciless as it poked at the foibles of his critics. This kind of poem positions readers as potential allies: it seeks to persuade them to join the author in laughing at a target by showing off the author’s humorous, linguistic dexterity. Achieving that goal could be tricky. After all, if you seek to convince readers that the object of fun is a vulgar dunce, you need to avoid any indication that you, too, might be tasteless or foolish; it requires a careful balance of pitch-perfect humor lest readers start to feel sympathy for the target. The job becomes even more difficult if the poem features two authors trying to duke it out for superiority. As Ogilvie and Grant took turns throwing punches in the course of The Ogilviad, neither exactly triumphed in the end. Grant got the chance to start the poem, but Ogilvie got the last word. Who was the hero, and who was the dunce?3

Figure 5. Title page of [Grigor Grant and James Ogilvie], The Ogilviad, an Heroic Poem . . . (Aberdeen, U.K., 1789). The witty lines quoted here come from Alexander Pope’s Essay on Criticism (1711) so that, in case a reader missed the title’s homage to Pope’s Dunciad (1728–1743), they’d be reminded. Courtesy of the Special Collections Centre, Sir Duncan Rice Library, University of Aberdeen

Grant’s opening lines established the tone as mock heroism, setting up Ogilvie as a Don Quixote-like comical figure who foolishly believed he was the hero. “Without delay great Ogilvie did stride / Within the College wall, elate with pride, / To all that met him he the feat did tell / Of that important day the battle fell.” After a little more than a printed page of Grant’s verse, Ogilvie offered an answer of about the same length. Ultimately, each wrote three sections of attack of roughly equal length. Throughout, they charged each other of being scoundrels and poor poets. Even as they accused each other of plagiarism, both lifted phrases liberally from the poetry they studied in their college classes and most of all from Alexander Pope himself. Ogilvie charged Grant of being a coward who showed himself “unequal for the fight”; Grant retaliated by describing Ogilvie as a “pseudo-poet” who lived inside a “dirty den.” As The Ogilviad moved back and forth between the two authors, both boys sought to land effective blows—barbs that might win applause from their classmates, likely the most important witnesses to the battle.4

If boys hurling insults at one another can appear a timeless practice, the fight displayed in The Ogilviad very much illustrates a specific moment in time and the power of words for college boys.

Start with the insults themselves and what they reveal about an eighteenth-century culture of honor among gentlemen. Liar, scoundrel, or coward (as well as puppy, another insult levied several times in The Ogilviad, likening a man to a dog): these were fighting words, capable of causing deep, even unforgivable offense between men. Terms like these humiliated a man in the eyes of others. They hacked away at his position in society, his manliness, his gentility. Men did not hurl such words at another without understanding that consequences would follow: a challenge, a demand for a public apology, even a duel with pistols, for the only way to resuscitate one’s reputation after being offended was to stand up manfully and demand retraction. In the United States, for example, when Alexander Hamilton accused James Monroe of being a liar, Monroe called Hamilton a scoundrel, and the challenges ratcheted up from there. “I will meet you like a Gentleman,” Hamilton followed, showing he was man enough to address the challenge; “get your pistols,” Monroe replied. After several tense weeks of negotiations, they resolved their differences without meeting on the dueling ground, each believing his reputation had survived intact—a resolution achieved largely through delicate mediation by Monroe’s friend, Aaron Burr, who would kill Hamilton in a duel of their own several years later. Most affairs of honor between gentlemen likewise ended without bloodshed, but within this culture men could feel they had regained their honor only by showing themselves willing to stand up to the insults. When Ogilvie and Grant engaged in a war of words, they played at being adults, trying on the attitudes and manners of the men they wanted to become. In many ways, The Ogilviad represented a rehearsal for manhood in which the boys learned the power of insults and the appropriate manly behavior in response.5

When Grant and Ogilvie delivered their insults via the medium of poetic mockery, they added another layer to their attempts at one-upmanship: a command of language, a facility for deploying words and arguments that could reveal their social polish and advanced educations. To win this fight clearly required displaying linguistic panache. Ogilvie took his turn in their poetic battle by writing:

Ignoble coward, I’ve read thy jingling verse,

Which vainly strives a combat to rehearse;

Yourself, ev’n conscious of inferior fame,

Sent forth your empty rhymes without a name,

Attack’d your foe beneath the gloom of night,

And shew’d yourself unequal for the fight.

It was bad enough for Grant to offer up these verses anonymously (and what could be more cowardly than anonymity?); Ogilvie also charged him with writing “jingling verse” and “empty rhymes,” all indicative of his “inferior fame.” Just as they adopted masculine stances in fending off insults like coward and puppy, they sought to show off their superior knowledge, humor, and poetic eloquence, all in the hope of winning in the court of the opinion of their friends.6

An eighteenth-century college education sought to teach a gift for speech backed up by knowledge, and the gentlemanly bearing that accompanied both. Boys arrived in Aberdeen having learned from their tutors or grammar schools a solid grounding in Latin and at least an introduction to Greek, but they had just begun to learn to carry themselves like men accustomed to respect from others. In addition to the classics, geography, rhetoric, mathematics, natural history, logic, and metaphysics they learned at King’s College, boys needed to learn politeness and civility, qualities that would mark them as distinct from uneducated Scots.7

Figure 6. A South East View of Kings College, Old Aberdeen 1785. Watercolor. The college sat about a mile up the road from the thriving city center of Aberdeen, an area still called Old Aberdeen. Courtesy of the Special Collections Centre, Sir Duncan Rice Library, University of Aberdeen

Scottish college students learned in no uncertain terms that they needed to perfect their command of the English language in both writing and speech to distinguish themselves as intellectual equals to their English neighbors to the south. This message came explicitly from their professors. In an era when many rural Scottish people still spoke the Scots language—the language that the Scottish poet Robert Burns was just beginning to romanticize in his poetry and in songs like Auld Lang Syne during the 1780s—college dons saw nothing romantic about it. For them and for other educated members of the literary elite, Scots was improper, uncouth, even barbaric. To these figures, dropping Scoticisms into one’s speech, like to say isnae instead of isn’t, or do you ken instead of do you know, identified you as someone who insisted on clinging to crude markers of the untaught and the provincial. One of the most renowned Aberdeen professors of the day, James Beattie, worried that eliminating those words posed a nearly impossible task. He lamented that no education in the English language could teach Scots to attain “a perfect purity of English style. We may avoid gross improprieties, and vulgar idioms; but we never reach that neatness and vivacity of expression which distinguish the English authors.” Even the best Scottish writers, Beattie believed, “have always something of the stifness and awkwardness of a man handling a sword who has not learned to fence”—and he reluctantly admitted that his own writing suffered. In his courses he urged his students to study English authors in order to improve their command of the written and spoken language. He even handed out lists of some two hundred Scots words that “must be avoided, because they are barbarous, and because to an English ear they are very offensive, and many of them unintelligible,” as he explained in a lecture. (And, in fact, James Ogilvie left no evidence that he ever used Scoticisms in his writing or his speech.) Beattie also advised students to try to learn to speak with “the English accent or tone” and as much as possible abandon “what is most disagreeable in his national or provincial accent.” How should a Scottish boy learn such an accent? By “conversing with strangers, or with those who speak better than himself.”8

Beattie particularly held up as a model the elegant language of the early eighteenth-century magazine The Spectator, a periodical so influential that thousands of miles away in the American colonies the teenaged printer’s apprentice Benjamin Franklin would use it to teach himself a fluid, authoritative style. Just as Franklin saw the perfection of his writer’s skills as one key to a brighter future for a poor boy born in the American provinces, so Scottish college students scrupulously studied their command of English and learned to rid themselves of provincial linguistic habits because their professors assured them they would never win esteem otherwise.9

The Ogilviad illustrates boys’ seeking respect from their peers through words—and not just any words, but through the epic (and mock-epic) poetry that had such an important place in their educations. Colleges taught boys to admire and emulate great men of the past. From the very beginning of their years at King’s College, students scrutinized the speeches of Cicero, the great Roman senator, whose oratory revealed the highest ideals of a man mobilizing his vast stores of knowledge for noble purposes: to steer the Republic forward on the right path. They venerated the model of the righteous orator, the good and admirable man who used convincing arguments and appeal...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction. A Celebrity in the Early Republic

- 1. The Ogilviad; or, Two Students at King’s College Fight a Duel in Poetry, 1786–1793

- 2. “Restless and Ardent and Poetical”: An Ambitious Scottish Schoolteacher in Virginia, 1793–1803

- 3. Ogilvie and Opium, a Love Story, 1803–1809

- 4. A “Romantic Excursion” to Deliver Oratory, 1808

- 5. Navigating the Shoals of Belief and Skepticism, October–November 1808

- 6. How to Hate Mr. O, 1809–1814

- 7. A Cosmopolitan Celebrity in a Provincial Republic

- 8. Forging Celebrity and Manliness in a Toga, 1810–1815

- 9. Fighting Indians in a Masculine Kentucky Landscape, 1811–1813

- 10. A Golden Age of American Eloquence, 1814–1817

- 11. A Fall from Grace; or, Oratory versus Print, 1815–1817

- 12. “A Very Extraordinary Orator” in Britain, 1817–1820

- 13. The Meanings of Melancholy, 1780–1820

- Epilogue. Celebrating and Forgetting

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index